Why we need to start taking the long view

Tektites are jet-black glass beads, created when drops of molten rock cool. They look like shiny mouse droppings. Tektites are what's left over after a big meteor crashes into the earth and melts the material on its surface, evidence of the destruction. They were found in Chesapeake, lining the impact creator that formed that bay.

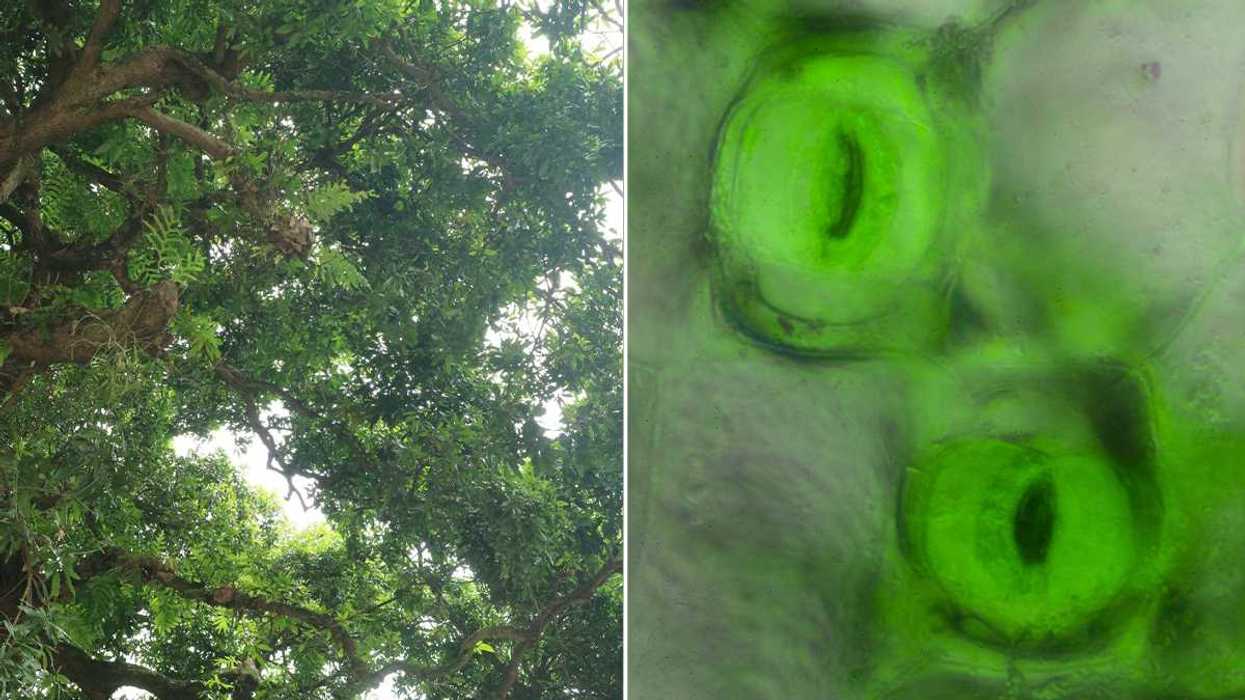

The tektites discovered on the Yucatan Peninsula in 1981 were cited as evidence of a huge meteoric strike-zone in the Gulf of Mexico. Three years before this, a geophysicist named Glen Penfield made an airborne magnetic survey of the Gulf's seafloor, just north of the Yucatan. He matched his data to some older maps his company had on file and found the same thing the tektites proved: A huge crater, 110 miles in diameter, had scooped out chunks of Mexico's southern and eastern flanks along the Caribbean.

Penfield worked for Petroloes Mexicanos, or Pemex, a state-owned oil company. Pemex wouldn't let him publish specific data, but Penfield was able to present his general findings at the Society of Exploration Geophysicists conference in 1981, the same year as the tektite evidence.

A generally accepted theory formed around Penfield's evidence and the tektites: A meteor 6-miles wide slammed into the earth just north of the Yucatan coast 65 million years ago, ending the dinosaur's reign. The meteor's impact created waves thousands of feet high, and was 20 million times more powerful than the most powerful atomic bomb. Sudden and violent events like this may make for good stories (though Deep Impact was pretty terrible), but most of the major changes our planet has experienced have happened another, much less cinematic way. Real significant change usually comes so slow it's hard to even notice.

There are two ways to look at the next million years we may or may not have on earth: the comet and the canyon. The comet represents a belief that the earth is shaped by single gargantuan events that we can't do anything about (except, maybe, if you call in Bruce Willis). The canyon represents slow, profound change over millions and millions of years. The comet is fatalism; the canyon, gradualism. The comet is the hare and the canyon is the tortoise. And even though it may not be flashy, like the tortoise, the canyon wins out every time. Now, more than ever, we need to remember the canyon when we think about how things change because we're shaping the earth, leaving it less habitable for ourselves, every day.

There were about 150 million gallons of oil in the Gulf on Independence Day. A number that big is hard to conceive—the slick is now larger now than most states, and has a greater surface area than the crater off the Yucatan. In all likelihood, we will still be watching this saga unfold in August, and the oil will be there long after summer's gone. But there are elections in November, and plenty of distractions until then. We are human and time moves faster for us than it does for our planet. The size and significance of what is happening in the Gulf is geologic. To comprehend the spill, to understand any very large occurrence on Earth, it helps to take the long view, the canyon view. Geologists start with a million years.

The canyon view is crucial at this moment because political cycles, news cycles, all human cycles, really, are so short. And the fact will remain, even as we watch the water blacken and the pelicans perish, and even once the spill is stopped, that we live in an oil-driven world. There's real danger in expecting anyone other than ourselves to make it otherwise. In his book Basin and Range, John McPhee writes, "If you free yourself from the conventional reaction to a quantity like a million years, you free yourself a bit from the boundaries of human time. And then in a way you do not live at all, but in another way you live forever."

In this sense, everything matters, especially the little things, because they echo through time and are the forces of real significant change. A single, disruptive event like the Deepwater Horizon spill isn't going to end oil drilling. There's simply too much money in it, too many economies that run off it. We can do every small thing in our short time on this planet to lessen our impact, though. We can start wondering what will be left behind long after we are gone, evidence of our species impact on earth. We can start asking ourselves what our tektites will look like.

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.