Stephanie Grisham, communications director for Melania Trump, will replace Sarah Huckabee Sanders as White House press secretary. Sanders’ controversial tenure will end June 30.

Critics claim Sanders rejected the public service aspect of her position by misinforming the public and refusing to renounce the president’s “enemy of the people” label of the press.

Sanders held fewer daily press briefings than any of her predecessors and effectively stopped briefings altogether in March of this year. Analysts say her legacy will be the death of the press briefing, a decades-old tradition used to inform the press, and by extension, the American public.

We are media scholars. At a time when the office of White House press secretary is the focus of controversy, we believe the first person to hold the position, journalist Ray Stannard Baker, could be a role model for Grisham and future press secretaries.

‘He is absolutely honest’

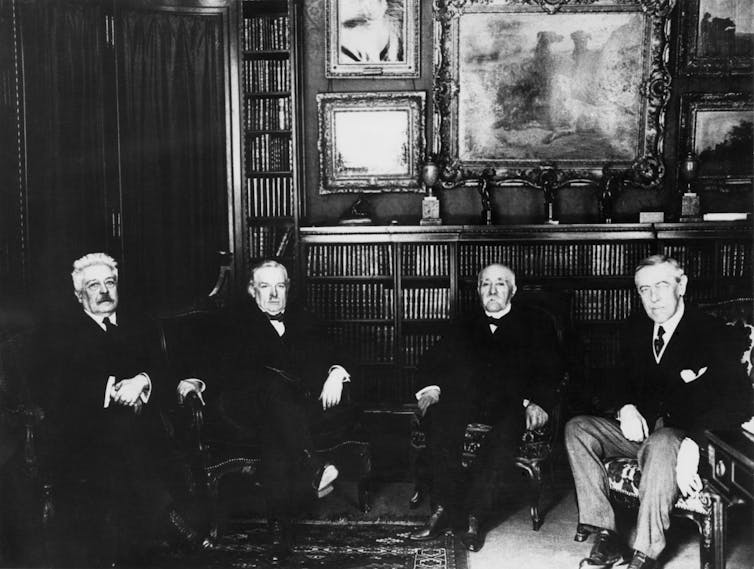

Baker was appointed by President Woodrow Wilson in 1918 to handle publicity for the American Commission to Negotiate Peace, which traveled to Paris to craft an agreement at the end of World War I. In those days of progressive journalism, the word publicity had a positive connotation of enlightening citizens about government activity.

Good press relations has been recognized as an integral part of presidential leadership since the William McKinley administration. The McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt and Wilson administrations each developed new techniques to manage publicity, including the use of press releases and presidential press conferences. One of these innovations was White House secretaries who dealt with the press as part of larger portfolios.

Even though Stephen Early of Franklin Roosevelt’s administration was the first presidential press secretary in both title and function, our research shows Baker was the first person to serve as a president’s full-time, personal intermediary with the press.

When Wilson tapped him for the publicity job, Baker was concluding a nearly yearlong mission as a special assistant to the Department of State. He had traveled to Europe to assess the outlook of liberal and labor groups, whose support Wilson needed for a cooperative peace.

Wilson described Baker as “a man of ability, vision and ideals.” He believed the journalist’s “esteemed” reputation among the news correspondents would be “most advantageous” to the success of the commission’s publicity work.

Baker was well qualified for the publicity role. A study of his personal papers shows he was judicious in his opinions and self-reflective. He had credibility: At his peak, he “was considered the greatest reporter in America” by his readers and peers, according to historian Louis Filler. He had integrity: He wrote a pathbreaking book on race relations. He was principled: He supported individuals, not political parties, depending on their ideas.

“[Baker] is distinctly the ablest man we have had in charge of news dispensing since the war began,” one correspondent wrote in an unsigned note found among Baker’s papers. “He is absolutely honest and he works in our behalf until very late.”

Baker also had a democratic understanding of the role of press secretary. He articulated this in 1921 when he looked back on his experience in Paris.

“I honestly endeavored at Paris to do the real work of publicity, getting out the facts & the background, as well as to report exactly what was being done, so far as I was permitted to do,” he wrote.

A new diplomacy

The Paris Peace Conference was a high historical moment. It marked the end to the most devastating war up to that time and the beginning of negotiations for a first-ever plan for permanent world peace.

Some 500 journalists – including 150 Americans – traveled to Paris to cover the conference.

Baker believed the American peace commission was a “great public undertaking” that required open communication with the people of the world. He believed publicity would be the heartbeat of American diplomacy.

With the end of wartime censorship, many journalists shared Baker’s hope for a “new diplomacy” that was transparent and reflective of public opinion.

Instead, the leaders of France, Britain, Italy and the U.S. agreed to closed-door negotiations.

The American correspondents felt betrayed by Wilson, who had called for “open covenants of peace, openly arrived at,” in his famous Fourteen Points speech in January 1918.

Baker did his best to help the correspondents get news.

One of Baker’s innovative ideas was for experts to draft briefing papers on “various highly complex situations” for the correspondents, many of whom had little experience covering foreign affairs. He arranged press interviews with the experts as well. Baker also played a lead role in preparing a 14,000-word summary of the treaty that was released around the world.

After lobbying Wilson, Baker successfully gained American correspondents access to Versailles to witness the first meeting between the Allied powers and Germany.

Baker believed that the success of his position depended on positive, friendly relations with reporters. In a show of mutual respect and cooperation, Baker helped form the American Press Delegation, a press association that acted as an intermediary between Baker’s office and the correspondents.

‘Not going to lie to you’

Reporters trooped to Baker’s Paris office in such large numbers they wore its aged, red carpet to shreds.

For Baker, truth and publicity were the guiding principles of press relations. In one of his first meetings with correspondents, Baker said, “I am not going to lie to you. If I am entrusted with information that I am required not to pass along I am going to say frankly that I cannot tell… as far as possible I will make reports of facts I have to give uncolored by my own opinions or desires.”

Baker met with the president each evening. Afterwards, he briefed reporters on what transpired during the day, to the extent the president allowed.

While Baker was never accused by reporters of lying or withholding information, correspondents became frustrated with Wilson’s secrecy. Baker, who “did not sanction the desire for secrecy that underlay the decision to bar reporters” from conference proceedings, repeatedly urged the president to meet with the correspondents. According to Baker, Wilson met with the press only three or four times.

Of course, Baker did not make every correspondent happy. But he took reporters’ expectations seriously. He accepted that journalists, as part of their jobs, were skeptical. He knew that some of the correspondents were bitterly opposed to the president. As a former journalist himself, he understood that reporters’ primary loyalty was to facts, not the administration.

“I knew well… the dread felt by every really able writer, and we had some of the best from America, of being used by propagandists for their own ends,” Baker wrote in his diary.

The most significant barrier to realizing Baker’s vision of serving the public interest was the absence of the President Wilson’s earnest engagement. Baker believed the “greatest failure” of the peace conference was the “failure to take the people into our confidence.”

Wilson’s preference for keeping the press at arm’s length contributed to his failure to convince the U.S. Congress to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and join the League of Nations.

Wilson’s defeats are a warning to presidents and their press secretaries. Public servants can leave no better legacy than respect for democracy – and a crucial element in that respect is transparency.

As Baker put it: “Publicity is indeed the test for democracy.”

Meghan Menard McCune is a Ph.D. candidate, Manship School of Mass Communication, Louisiana State University. John Maxwell Hamilton is Global Scholar at Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, DC and Hopkins P Breazeale Professor, Manship School of Mass Communications, Louisiana State University.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation. You can read it here.

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.