This post is brought to you by GOOD, with support from UPS. We’ve teamed up to bring you the Small Business Collaborative, a series sharing stories about innovative small businesses that are changing business as usual for their communities and beyond. Learn how UPS is helping small businesses work better and more sustainably here.

*******************

Every family has one: the photo box filled with dusty black-and-whites. Some have names scrawled across the back—great-aunts and uncles adorn the front, frozen in a youthful moment that has long since faded from memory. But some snapshots inevitably lack any identifiers, leaving us wondering who these people were, how they share our roots. It’s a little mystery stowed in a shoebox, and we simply can’t bear to throw them away.

Chris Kious lives this experience, but on a citywide scale, every day. He had spent five years working for a Cleveland community development organization, working on an inventory of around 100 abandoned houses in just one neighborhood. Thanks to depopulation, foreclosures, and antiquated floor plans—think one bathroom, no garage—thousands of century-old homes have been left to crumble throughout the city. These properties correlate with lower property values for neighbors, higher crime rates, squatters, drugs—and so, according to the City of Cleveland Building and Housing Department, the city has proactively demolished 6,323 homes since 2006. It’s a needed service, but history is often lost as these old homes are razed. Just as importantly, a stream of raw material is trucked off with each demolition.

Elsewhere in Cleveland was designer P.J. Doran, an artist and craftsman who had been making “things” from garbage picks, leftovers and salvaged building materials since he was a kid. As he developed into a tradesman in the home construction industry, he was staggered and frustrated by the immense waste involved in new construction, and so he began designing and building custom furniture from reclaimed materials. His work was a spark of inspiration, and in 2007, Kious and Doran recognized an opportunity. A Piece of Cleveland got its start, and from carefully deconstructed homes on the city’s demolition list, new feature walls, counter tops, tables and chairs are reborn.

“I’m in a race against time to rescue as much of this material as possible, because the other side of the coin is that Cleveland was built at a time when wood was good,” says Kious. The city’s boom times came post-Civil War, and well into the turn of the century the city attracted immigrants and people from rural areas and the South. To build their homes, there followed a stream of old-growth Southern Yellow Pine from trees that Kious estimates had to have been between 20-40 inches in diameter. It’s not exactly the farmed wood you can buy at a big box home improvement store nowadays.

“I’m not chopping down old-growth forests,” says Kious. “That was a hundred years ago. I’m just trying to keep it out of the landfill now.” Deconstructing houses for the city, they uncover pine, Douglas Fir, White Oak and maple. It’s top-quality lumber that can’t be found in many other older cities.

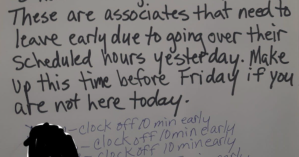

But a home is more than just its guts of wood and plaster. “We find pennies all the time,” says Kious, presumably tossed into walls by builders for good luck. Often, behind mantel pieces, APOC finds family photos, old birthday cards, postage stamps. Once Kious found what seemed to be the 1920s equivalent of pornography rolled up between the rafters in an attic: fully-dressed women, showing a bit of leg. “It was really naughty stuff,” Kious laughs.

APOC wasn’t sure what to do with that particular stash, but they find it difficult to throw any of these artifacts away. “It’s really hard. We are, by nature, sort of hoarders when you think about it.” What isn’t fire- or water-damaged gets scanned and filed. For every house they deconstruct, a researcher also digs into local records to see who lived, was born, and died there. From the materials salvaged in these homes, new tables, chairs and coasters are made—and issued a “rebirth certificate” that captures a bit of the material’s history. When family members can be located, old photos and cards are mailed to them.

It’s the story that sets APOC apart from most other upcyclers. Their customers range from former Clevelanders living abroad who want to take a piece of local history with them, to home-owners who can afford custom-made products. Primarily, it’s business owners, offices, architects and interior designers who buy their pieces because being able to tell a story—one of Cleveland’s past, one of resources salvaged—speaks to their values in ways that mission statements can’t.

The stories are collected out of a genuine love for the city, but it’s also smart marketing. “It’s an evolution of the notion that brands need to make an emotional connection with people,” says Gary Hunter, professor of marketing at the Weatherhead School of Business at Case Western Reserve University. In the broadening market for sustainable goods, it helps to connect customers with your product on another level. Says Hunter, “A product like this that makes an emotional connection and serves the needs of people who want sustainable products has enormous potential to develop a unique and cared-for brand.”

From the people who receive salvaged pictures in the mail, APOC hears back things like “That was my aunt and uncle who lived there. That’s so neat what you’re doing. Thank you!” Pieces of homes that would have been lost to history become chopping blocks for newly married couples or the table around which a new generation will share meals. APOC’s formula seems to be more than the typical upcycler’s mantra (“Hey man, you’re not going to throw that out are you?”). It’s about saving an object, but also what it means, and turning all of that into something new.

Photo of upcycled wood installed at Pura Vida restaurant via Dan Morgan.