Each year, GOOD celebrates 100 people from around the globe who are improving our world in creative and innovative ways—advocates, inventors, educators, creatives, business leaders and more who are speaking up, building things, campaigning for change, and ultimately refusing to accept the status quo.

In this section, meet 16 individuals reclaiming and reshaping spaces—urban, rural, figurative—to be more sustainable, inclusive, and safe.

Jeff Hebert Plots New Orleans’ Comeback

New Orleans

Few cities need Hebert’s job as much as his current employer, New Orleans. The Big Easy, which is still fighting to recover from massive devastation wreaked by Hurricane Katrina, hired the urban planner as its first chief resilience officer near the end of 2014. This year, Hebert will begin implementing “Resilient New Orleans,” a strategy that prioritizes infrastructure, inequality, and adaptation.

Sally Duncan Protects Playtime

Addis Ababa

Ethiopian urbanization is uniquely concentrated in Addis Ababa, the only urban area with more than 300,000 people in a country of over 90 million. As the capital continues to grow, Duncan wants to expand and democratize its public play space. Her company, Out of the Box, designs children’s recreational areas for low-income, high-rise condominium communities. Its first “adventure playground” opens this spring.

María Claudia Lacouture Puts Colombia On the Map

Bogotá

As president of Colombia’s official promotional agency, ProColombia, Lacouture has tackled her country’s dangerous, drug-fueled reputation with digital-age ingenuity. Tourism has increased by more than 50 percent during her four-year tenure, now outpacing exported coffee as a source of foreign revenue. She’s also helping turn the country into an international hotbed for tech, leading campaigns to encourage Colombians to enter the sector.

Kelly Ward Brings a Pen to a Gunfight

Washington, D.C.

As general counsel for the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, Kelly Ward developed the “gun violence restraining order,” allowing California officials as of January to temporarily confiscate firearms from those deemed a clear and present danger. Next on Ward’s agenda is expanding similar legislation across the country.

Liz Alden Wily’s Land Rights Revolution

Leiden

Rogue political economist Liz Alden Wily has spent decades contesting legal systems that deny community-based land rights. Now she’s fighting to put 6 billion hectares back into the hands of indigenous communities whose land tenures predate the existence of a state. Last November, she helped launch LandMark, an interactive digital map that provides information on land tenure history as well as national land and resource laws. She also started the African Land Rights Transparency Index, a biannual report on rural land rights policies in various states. The report will expand to include 25 countries this year and the entire continent by the end of 2017.

ShamsArd Gets Crafty In Palestine

Ramallah

Danna Masad, Lina Saleh, Dima Khoury, and Rami Kasbari of Palestinian design studio ShamsArd champion local earthen building materials and affordable, sustainable architecture. But as Israel tightened its grip last year on imports into Gaza and the West Bank—draining Palestine’s supply of concrete and cement—ShamsArd became vital for a new reason: It offers design solutions based on construction materials Palestinians can reliably acquire. The five-year-old firm has worked on homes, hospitals, and community centers; it’s currently collaborating on 20 new playgrounds.

Autowale Decongests India’s Streets

Pune

With the world’s second highest number of traffic fatalities, India clearly has a congestion problem. Janardan Prasad and Mukesh Jha are attempting to alleviate that with Autowale, an app, website, and phone-in service that functions like Uber for auto-rickshaws. Autowale connects customers with drivers of India’s ubiquitous three-wheelers, which facilitate 20 percent of the country’s urban trips while occupy- ing just two percent of the road. The company now employs over 1,000 drivers—many of whom have increased their monthly salaries twofold with the steady work—and has served half-a-million customers. This year Autowale is testing hyperlocal food, grocery, and e-commerce deliveries.

Ravi Naidoo Nurtures Africa’s Creative Class

Cape Town

Few are more responsible than Naidoo, founder of renowned creative agency Interactive Africa, for turning Cape Town into an international design hub. The annual Design Indaba Festival he launched in 1995 brings together Africa’s foremost and emerging creatives to exhibit, network, and reimagine the continent.

Sarah Lidgus Crowns Community King

New York City

As founder of the urban inequality-focused creative studio Small City New York, designer Sarah Lidgus’s community-based design practice aims to make cities friendlier, specifically by engaging its inhabitants in the process. She speaks passionately about building lasting relationships, understanding a project’s political context, and accepting the community as the expert. Last year, Lidgus launched a community design school in Queens, produced an employee rights guide for nail salon workers, and led a community art project in the South Bronx.

Beth Stryker Gives Cairo a Facelift

Cairo

An architect, artist, and curator by trade, Beth Stryker co-founded CLUSTER (Cairo Lab for Urban Studies, Training and Environmental Research) with architect/urbanist Omar Nagati in the Arab Spring’s aftermath, to foster urban research, architecture, art, and design initiatives. CLUSTER works to revitalize downtown Cairo, through long-term projects to reinvigorate the city’s passageways and rooftops as public space. The lab has also developed designs for a community park to integrate informal and formal neighborhoods, held participatory design workshops, and designed a model for urban eco-houses.

Thomas Granier’s Inspired Mud Masonry

Ganges

In sub-Saharan Africa—where desertification and deforestation are depleting natural timber resources and modern construc- tion materials can bankrupt families—20,000 people use or live in Thomas Granier’s “Nubian vault” homes, built with local, raw-earth bricks and based on methods invented over 3,000 years ago in Egypt. Formerly a mason’s apprentice, Granier co-founded the Nubian Vault Association in 2000 to reduce housing costs, battle climate change, and cultivate a new, smarter generation of West African masons. Last year, the organization expanded into its fourth and fifth countries, Benin and Ghana.

Sarah Drummond’s Pedal-Powered Movement

Glasgow

CycleHack started as an annual 48-hour event uniting citizens, government officials, and cycling agencies in cities around the world to prototype design solutions for cycling accessibility. It quickly grew into an online community sharing tricks year-round, like how to use a penny and rubberband to temp rarily makeshift a skirt into bike-friendly pants. This year, founder Sarah Drummond, proud owner of a blue racer named Lost Boy, is bringing the event to more than 70 cities and developing bike-friendly curriculum for schools.

Adib Dada Revives Polluted Rivers

Beirut

The Beirut River is more sludgy sewer than river, complete with rumors of a resident crocodile lurking in the muck. Adib Dada thinks he can clean it up. Using biomimicry techniques developed at theOtherDada, his architecture and design practice, Dada is attempting to rehabilitate the river and reintegrate it into Beirut’s natural ecosystem. He’s also rebuilding the city’s infrastructure around a more symbiotic relationship between nature and the built environment. The first stage, Beirut River 2.0, which addresses infrastructural decay and contamination in the most polluted neighborhoods, is currently under way.

Susannah Drake Soaks Up Pollutants

Brooklyn

Architect Susannah Drake’s DLANDstudio, a design firm that fuses landscape and architectural engineering, unveiled an ambitious proposal that fundamentally reimagined New York City’s oppositional relationship with water in 2010. Her vision starts to take shape when Gowanus Canal Sponge Park opens in Brooklyn this spring. Among other features, the park’s custom-engineered soil will absorb toxins and heavy metals from the canal’s heavily contaminated waters, which the EPA has estimated would take over $500 million to clean completely.

Carolina Osorio Fights Traffic with Formulas

Boston

There’s a good chance the next generation of urban transportation systems will run on algorithms developed by Carolina Osorio. The Bogotá-born civil and environmental engineer, currently an associate professor at MIT, builds real-time traffic management strategies and models derived from advanced math theory that use high-resolution urban mobility data collected on smartphones to reduce urban congestion. Simply put, your future commute is looking a whole lot nicer.

Facundo Guerra Revitalizes Sao Paulo Nightlife

São Paulo

Urban entrepreneur and nightlife architect Facundo Guerra injects culture and revelry into the areas of São Paulo that need it most. As one of the leading forces behind the city’s cultural resurgence, Guerra brings a forward-looking nostalgia to his transformation of run-down, seedy street corners into vibrant nightlife hotspots that rejuvenate, rather than replace, seasoned establishments. His revival of Riviera, a locally cherished bar that closed in 2006, and opening of Cine Joia, a 1950s cinema-turned-music-venue, have landed Guerra on the list of São Paulo’s most buzzworthy tastemakers.

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

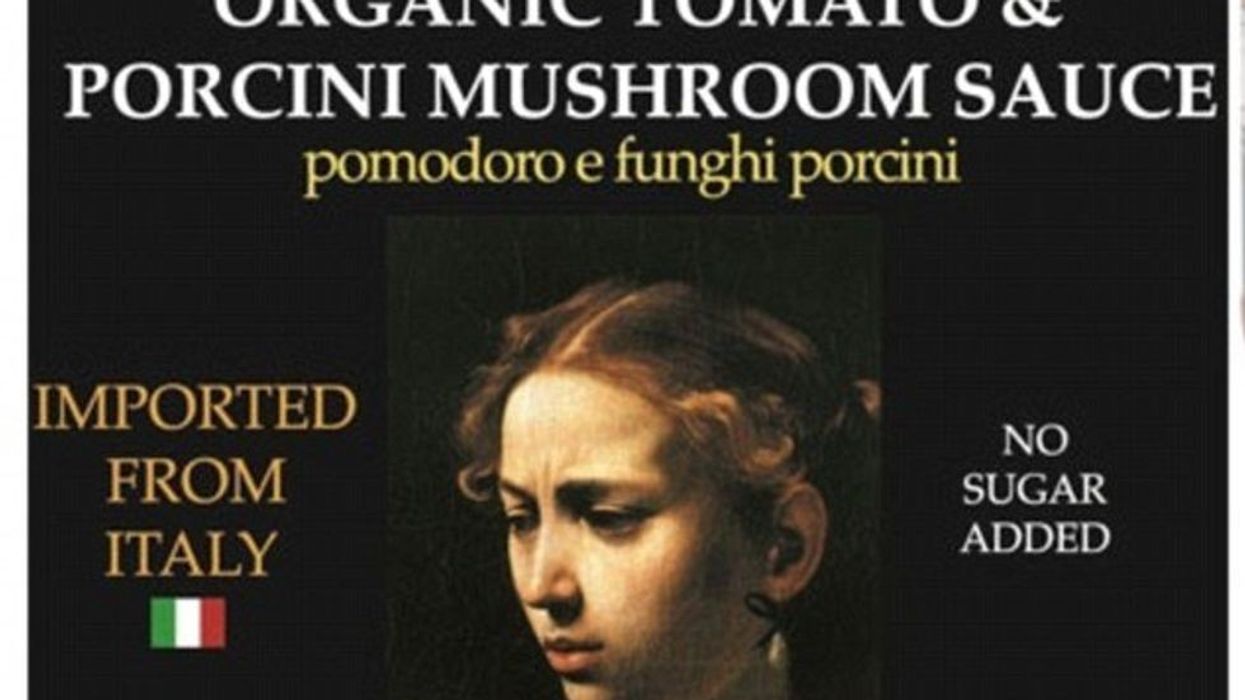

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)