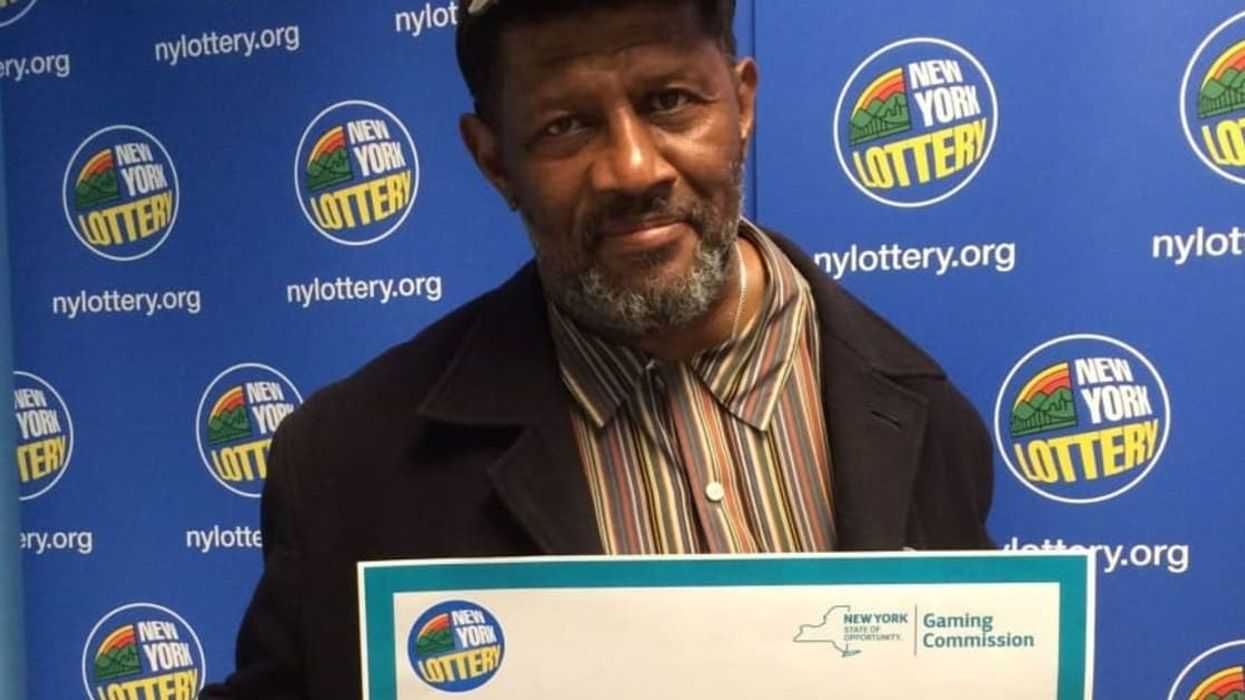

Just a few years ago, Nelson served 90-days at the notorious Rikers Island jail for making an illegal U-turn. If that seems unreasonable, it’s because it is. Under current law, individuals on parole can be re-incarcerated for weeks, months, or even years for violating the conditions of their parole, such as being late for curfew, fare evasion, changing one’s residence without permission, or making a U-turn. The circumstances are often inconsequential. When individuals are re-incarcerated for these non-criminal offenses, they are referred to as technical parole violations (TPVs). While the number of individuals entering our prisons for new crimes is on the decline in many states, those incarcerated for TPVs is increasing significantly, revealing a disturbing trend in our criminal justice system.

New York State is a primary example of this trend. In 1999, New York State held 72,649 incarcerated individuals. However, according to the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, of March 1, 2019, state prisons held 46,875 individuals, a 35.5% reduction. However, while NYS has been a leader in reducing crime and incarceration rates, its prison admission rate for TPVs is the 14th highest in the country. Additionally, in 2014, 38% of prison admissions in New York were the result of parole violations and since then, we’ve seen the number increase by 15%.

When Nelson received his violation, he lost his job and several of his personal relationships were strained. He had important life responsibilities and his family was depending on him to help pay the bills and care for his children. It didn’t matter that he had made progress since release, or that TPV incarcerations cost taxpayers tens of thousands of dollars and disrupt the process of recovery and the road to success for many individuals. At The Fortune Society, we connect this to desistance, generally defined as the cessation or absence of offending or other antisocial behavior. After release from incarceration, many individuals refrain from engaging in criminal behavior, in spite of the struggles they encounter in the reentry process. During this period, these individuals may be employed or pursuing education, building pro-social relationships, and trying to maintain stable housing, among other things. Sending them back to prison for TPVs has the potential to impede any success they have made. In addition, TPVs inflate recidivism statistics, since these individuals are classified as “recidivists” for violating parole, or engaging in non-criminal offenses.

Why is the recidivism net cast so wide? It’s hard to say, but it’s clear that as a country we are fanatical about recidivism; indeed, it is often the only metric we use to measure outcomes in the criminal justice system. Recidivism is a measure of “failure,” whereas, desistance is a measure of success. We focus obsessively on why individuals fail in their return home, but we pay scant attention to the factors that promote success.

To that extent, we need to learn more about the detrimental impact of TPVs on individuals and the community. For example, when it comes to parole officers, while some are incredibly helpful, others are quite strict and limiting, making it difficult for individuals to thrive. It is particularly harmful when a P.O. paints everyone with the same brush and fails to acknowledge them for achievements and productivity. At the Fortune Society we say “the crime is what you did, it’s not who you are.” We reject the notion that anyone should be defined exclusively by prior bad acts, or judged into perpetuity for poor choices. Indeed, we think that fixing the parole system involves looking at the positives and successes of the people who move through it as lessons on how to affect real change.

Further, we think it’s necessary to educate people about TPVs and the impact they have in keeping individuals tethered to the system, what some refer to as doing life “on the installment plan.” There are important ways we can and must shed light on, and fix, this important issue: we can spark conversation by bringing policy makers, corrections officials, and practitioners together to build a more nuanced understanding of this issue; we can engage in research on desistance; we can pass legislation like Senator Benjamin’s Less is More Act to reform New York’s broken parole system; and we can have people with lived experience share their stories.

As a society, we need to release our grip on the failures associated with the system, and learn about successes in the transition from prison by focusing on those who are abstaining from crime in the face of tremendous adversity. We must remember, too, that there is no evidence that returning individuals to prison for TPVs makes our communities safer. To the contrary, individuals, families, and communities are harmed when someone like Nelson is returned to custody for making a U-turn. We can and must do better.

Ronald F. Day, Ph.D., is Vice President of Programs at The Fortune Society in New York City. He is passionate about reentry, promoting desistance, dismantling mass incarceration, and addressing the stigma of incarceration.

Nelson Rivera is a Supportive Housing Specialist at The Fortune Society in New York City. He is also involved in advocacy and is dedicated to fixing the parole system, educating others, and sharing his lived experience.

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.