Oftentimes, when attending professional sporting events, I exclaim such words as “boo” and “hooray,” and when I’m really exhilarated, even vigorously thrust my palms together to create a “clapping” sound. Sadly, I performed none of these actions at a San Francisco 49ers game in October, despite having traveled all the way from Los Angeles just to go to Candlestick Park. I didn’t cheer because I was too intimidated by the rowdy fans around me, all of whom seemed to be drunk, 6’5” and built like Zambonis.

I was afraid of the intoxicated gentleman in the next row who directed “shut the f--- up” at a little girl, as well as the maniac who unleashed a primal scream in my face because he could tell I was a New York Giants fan (I dressed in neutral greens and blacks—a dead giveaway). Also contributing to my anxiety was the rumor that a man was stabbed in the parking lot before kickoff (which turned out to be true). I basically paid $200 for three hours of suppressing cheers and concealing fist pumps.

The “fans” around me weren’t even commenting on the game; there were no mentions of plays, penalties, or players. I remember someone barking “We have to retaliate,” which sounds more like a war cry than cheering for the home team.

Soccer hooliganism became rampant in England in the 1960s, but I suspect that fan violence was born when the first fan attended the first event. I highly doubt the ancient Romans watching gladiators fight and kill wild animals sat calmly with their families and golf-clapped while nibbling on grapes and respectfully remarking “carpe the tiger!” No, they most likely drank seven jugs of overpriced wine then beat the living crap out of each other.

In the last couple of years, fans at American sporting events have been beaten, robbed, vomited on, and even shot. The Miami Dolphins have implemented a real-time security alert system to be able to respond to incidents more quickly, and organizations like Fans Against Violence are trying to spread awareness. But with a vast majority of their revenue streams coming from television, teams seem to be increasingly less concerned with even getting fans to the stadium, much less how they’re treated once inside. And many of the measures teams have taken are a response to violence that has already occurred, as opposed to a preventive measure implemented before an incident.

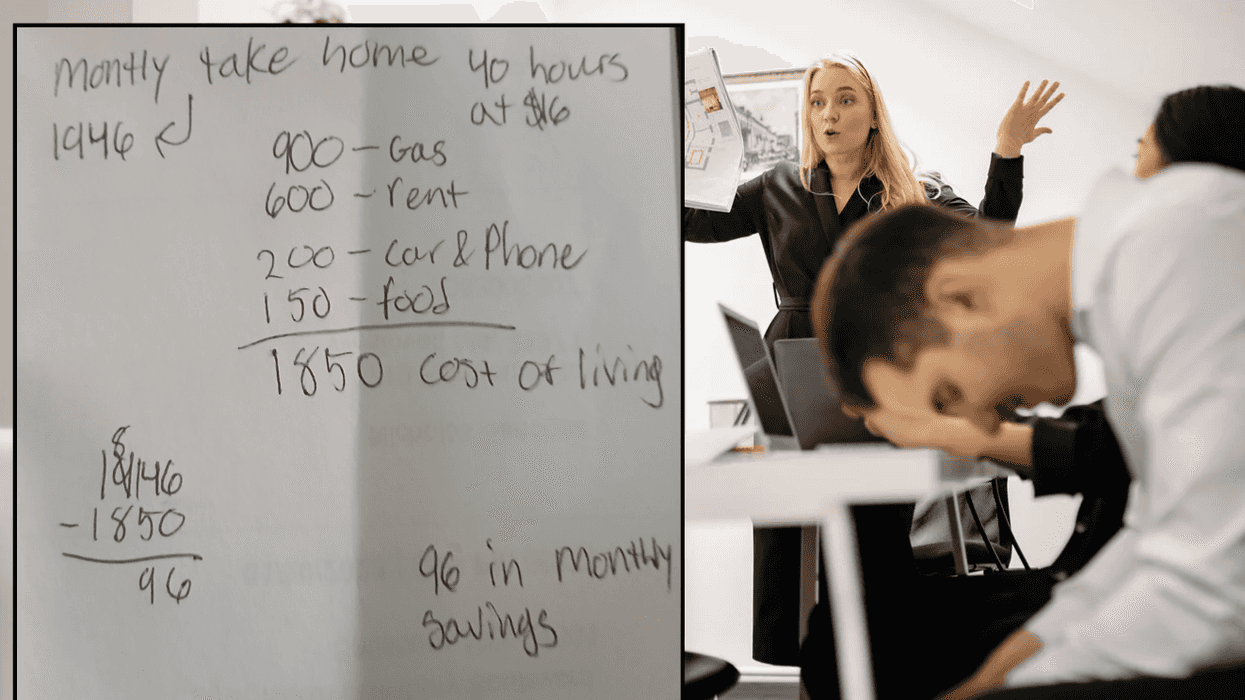

One could place blame on a number of things: alcohol, the fact that football is a vicious sport, or the glorification of violence in pop culture. But I suspect the truth may lie in a much deeper place: that people attend sporting events not despite the raucous atmosphere, but for the raucous atmosphere. Maybe your average American, either unemployed, underpaid, or overworked, somehow needs that release. Maybe it doesn’t matter how much security is added or alcohol is restricted. Maybe people will continue to be violent simply because they want to be.

Last year, Ndamukong Suh of the Detroit Lions wished Green Bay Packer Evan Dietrich-Smith a happy Thanksgiving by stomping on him after a play. I watched this from the comfort of my grandmother’s living room, snuggled cozily in a blanket with a belly full of turkey. The NFL has cracked down on egregious displays of violence between players such as that one, but much is yet to be done in terms of discouraging fan-on-fan attacks.

Until some changes are made, I’ll probably continue to spend my Thanksgivings sitting in front of the television instead of sitting in front of an inebriated, angry fan who might coldcock me after a touchdown. I still won’t be cheering too loudly, but it will be to avoid waking up Grandma, instead of avoiding a stabbing.

Illustration by Corinna Loo

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.