This is Farmworker Awareness Week but how many of us are aware of the critical role of farmworkers much less aware that there’s even a week dedicated to them? We eat 280 million pounds of fresh fruits and vegetables a day—from supermarkets, restaurants, cafeterias and fast food establishments. And all of it is picked by hand.

Ironically these workers are among the most abused and poorly paid people in the nation. As longterm farmworker advocate Eva Longoria says, “This is not an immigration issue. This is a human rights issue.”

I’m a filmmaker by profession and in my new film Food Chains to be released later this year, I dig deeper into the injustices in farm labor, after being inspired by an early morning drive in the summer of 2011. I was in south Florida, following my iPhone’s schizophrenic GPS directions as I drove from beachside Ft. Myers to Orlando for a flight back to New York. Rather than take me up the six-lane superhighway, my phone took me on the shortest route– through swampy central Florida. It was dark. I was tired. I didn’t know any better.

[vimeo][vimeo https://vimeo.com/40126039 expand=1][/vimeo]

After a few hours, I saw the light of a bodega that was just opening. I parked and went inside for some coffee. The interior reminded me of Haiti or Cuba—the shelves were bare. But as in those two countries, the coffee smelled great and I paid and left.

In the parking lot a school bus pulled up and a few dozen Latino farmworkers shuffled inside for the same reasons I did. I was hungry too but didn’t dare experiment with the food the bodega owner was preparing. I don’t think my stomach’s digestive enzymes were up to the task.

In California, where I grew up, I was accustomed to farmworker towns in the Central Valley. The ranchers and supervisors usually live in nicer areas between 10 and 20 miles away from those hamlets. But this was the South, and economic segregation didn’t necessitate geographic separation. Just two blocks from this bodega was a gleaming, bright diner serving people who definitely were not farmworkers.

The end of legal apartheid, the forced segregation between African Americans and whites in the South, didn’t erase economic barriers. And while rich and poor communities are never physically integrated with one another, the geographic boundaries between them can disappear in the South. And here in Central Florida, once home to plantations and then labor camps, the well-off people were not the same color as the poor ones.

The proximity between the bodega and diner was not as glaring a “colored” water foundation next to one for whites. Legally, of course, the farmworkers had a choice. They could quite simply walk up the street, into the diner and expect service. Practically, though, these workers had no choice. A meal at that diner could cost them two to three hours pay as opposed to a half hour’s. This wasn’t legal apartheid. This was in fact economic apartheid—where things were separate and not equal.

It struck me that if the farmworkers I had seen had been African American instead of Latino, I could’ve been in 1911 not 2011. And I guessed that the power dynamic these Latino workers faced in the field was similar to what workers faced 100 years ago.

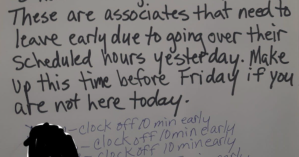

Farmworkers, whether documented or not, aren’t protected by the same labor laws as the rest of us are. They are also paid by how much they pick which pits workers against each other to harvest more than one another—in the heat and without regular water breaks.

Worse, the power dynamic in the fields is akin to that of a master and serf. Workers are too intimidated to complain when their rights are violated. Women can be raped and are regularly harassed. In the worst cases, workers have actually been enslaved: working for no pay and under the threat of beatings or death.

The undercarriage of our magnificent food production system, second to none, is rusted and decayed. The system is fueled by inequity and fear.

But it doesn’t have to be.

A valiant group of tomato pickers from southern Florida, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers has successfully fought multibillion dollar retailers to use their power to change the system. These companies, like Taco Bell, Trader Joes and McDonalds, now use market pressure to ensure that conditions on farms in Florida at least are safe, human and dignified. They also pay an extra penny per pound of tomatoes, which amazingly doubles the wages of workers.

The sixth largest grocery chain, Publix, for example, had about $30 billion in gross revenue last year, three times as much as Monsanto. These large retailers are directly responsible for keeping farmworker wages low by paying farmers less and less, who consequently cannot afford to raise farmworker salaries. These retailers also have the power to ensure farmworkers are treated correctly.

Some like Whole Foods and Trader Joes are using their power for good. Others, like Publix, are not.

This week, let’s take a moment to reflect on the hands that feed us, to recognize the contribution of farmworkers to our well-being, and to recognize that that which sustains us leads to their abuse. And that we can change this. Support farmworkers rights and groups like the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. They are fighting to ensure their future, which, is, in fact, our future.

Sanjay Rawal is the director of an upcoming documentary FOOD CHAINS starring Eric Schlosser, Eva Longoria, Dolores Huerta and Barry Estabrook. The film’s Executive Producer is Eva Longoria. The film is produced by Smriti Keshari and Hamilton Fish.

This post is part of the GOOD community’s 50 Building Blocks of Citizenship—weekly steps to being an active, engaged global citizen. This week: Learn to Cook a Dish With a Story. Follow along and join the conversation at good.is/citizenship and on Twitter at #goodcitizen.