In the months after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the military to move Japanese-Americans into internment camps to defend the West Coast from spies.

From 1942 to 1946, an estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans, of which a vast majority were second- and third-generation citizens, were taken from their homes and forced to live in camps surrounded by armed military and barbed wire.

After the war, the decision was seen as a cruel act of racist paranoia by the American government against its own citizens.

The internment caused most of the Japanese-Americans to lose their money and homes.

Actor and activist George Takei was taken to an internment camp when he was just five years old.

"It was, for my parents, a harrowing experience," Takei told ABC. "Just imagine, the government takes everything from you, everything that you worked for, in the middle of your life, and to have your business, your bank account, the home that you built taken away from you, and unjustly imprisoned, and having soldiers pointing guns at you… with our children."

Takei and his family were first imprisoned at the Santa Anita race track outside of Los Angeles, before moving to a camp in Arkansas.

"We looked exactly like the people that bombed Pearl Harbor," he said. "Money was never, you know, returned. It was gone. And our home. You couldn't make mortgage payments. That was lost. We were stripped naked and brought here to a smelly horse stall."

California was home to an estimated three-quarters of those interned in the camps.

"California was at the forefront for pushing for some of the policies that led up to internment," said David Inoue, executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League. "And many people within the state of California advocated for them."

Now, nearly 80 years later, the state is finally ready to officially apologize.

The resolution, introduced by State Assemblyman Al Muratsuchi on Jan. 28, is expected to receive broad support from the rest of the Assembly.

The resolution says the California Legislature "apologizes to all Americans of Japanese ancestry for its past actions in support of the unjust inclusion, removal, and incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II, and for its failure to support and defend the civil rights and civil liberties of Japanese-Americans during this period."

The resolution was inspired by the Trump Administration's recent efforts to detain and separate the families of undocumented immigrants from Mexico, South and Central America.

The resolution states that "given recent national events, it is all the more important to learn from the mistakes of the past and to ensure that such an assault on freedom will never again happen to any community in the United States."

While California's apology comes more than a few decades too late, the federal government apologized for the atrocity 42 years after the camps were closed. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, which claimed the internment was sparked by "racial prejudice, wartime hysteria and a failure of political leadership."

The same year, the Senate voted to give $20,000 and an apology to each of the people forced to leave their homes.

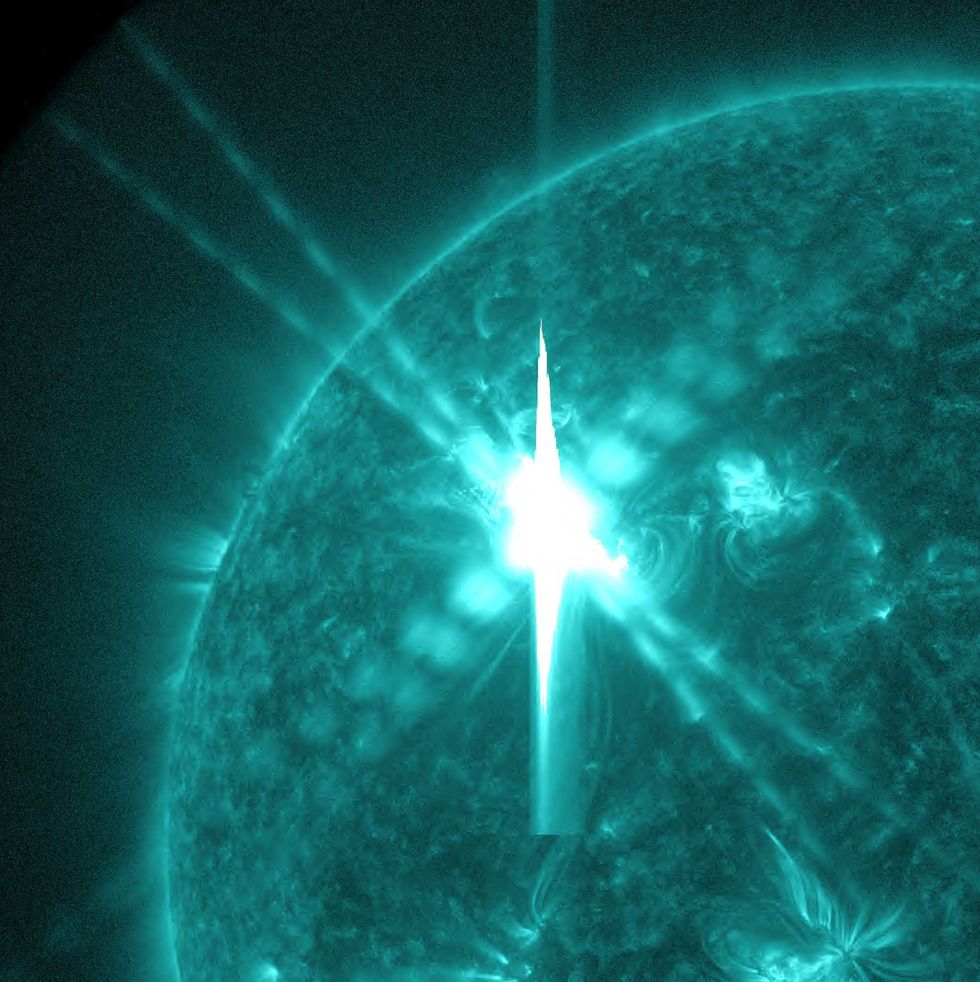

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Ladder leads out of darkness.Photo credit

Ladder leads out of darkness.Photo credit  Woman's reflection in shadow.Photo credit

Woman's reflection in shadow.Photo credit  Young woman frazzled.Photo credit

Young woman frazzled.Photo credit

A woman looks out on the waterCanva

A woman looks out on the waterCanva A couple sits in uncomfortable silenceCanva

A couple sits in uncomfortable silenceCanva Gif of woman saying "I won't be bound to any man." via

Gif of woman saying "I won't be bound to any man." via  Woman working late at nightCanva

Woman working late at nightCanva Gif of woman saying "Happy. Independent. Feminine." via

Gif of woman saying "Happy. Independent. Feminine." via

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.