“We’ve had in the excess of 100 interviews, and we still haven’t found that one that doesn’t want it,” said Volvo technical manager Lena Ekelund in 2004. That March, the Swedish car manufacturer debuted the Volvo YCC, “Your Concept Car,” at the Geneva International Motor Show—then one of the most esteemed auto shows in the world. Even though cars had existed for nearly a century, the YCC was, as Volvo shared, “the first car designed and developed almost exclusively by women.”

Two years earlier in 2002, a group of female Volvo designers, engineers, and marketing professionals went to a seminar at the company to learn how they could improve their reach to female consumers. What they learned, Volvo shared, was that “women purchase about 65 percent of cars and influence about 80 percent of all car sales; yet, for a century, men have made most of the decisions in the design, development and production of a car.” Something needed to change. After all, if women were making the decisions, if they were buying their own cars, shouldn’t cars also reflect their needs? They petitioned Volvo to let them create a concept car, a prototype, informed by women’s driving decisions and desires. Not only did they make it, as Volvo shared, they did so “faster and at less cost than most concept cars.”

Though 120 people worked on the project, the Volvo YCC project leadership team was made of of nine women–Lena Ekelund, Anna Rosén, Maria Widell Christiansen, Camilla Palmertz, Tatiana Butovitsch Temm, Eva-Lisa Andersson, Elna Holmberg, Maria Uggla, and Cynthia Charwick.

The developments the Volvo YCC team made included movable back seats for more storage, gull-wing doors "that make it easier to load and unload larger items and children,” a seat that tailors itself to your body’s needs, specialized compartments, and a split headrest for a ponytail. Wiper fluid and gas would be reachable directly from the outside of the car without having to open the hood or the gas cap. The car would steer parallel parking itself, and would have “heel-adjust capability” so women wearing heels could angle their feet appropriately to accelerate, among many other features.

- YouTubewww.youtube.com

A more challenging innovation was the idea that the hood wouldn’t open and that the car would “[notify] the owner's chosen service center when maintenance is due” and ask the service center to get in touch with the driver, which could have become very dangerous and, well, kind of infantilizing, depending on who you are.

Some of the coverage of the Volvo YCC, often written by men, at the time also approached the car with some degree of condescension. One article shared that it was “all very touchy feely” and “almost more of a break with tradition than the Women's Institute members stripping off for a calendar,” referencing the English ladies “of a certain age” who produced a tastefully nude calendar to raise money for blood cancer research a few years earlier.

Another interviewer asked if men would feel comfortable in the car. And though it was designed by women, Ekelund shared that the car was, of course, meant for all. “Everyone wants more storage in the vehicles, and they want it safe and smart, and they also want to have a car that is easy to get in and out of,” she told NPR in 2004.

While the car was never produced, it still became an innovative and important foray into design by women and for women. As Ekelund said at the time of the car’s debut, "The hallmark of a good idea is that people ask why this hasn't been done before." Maybe there’s another one to come in the future.

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/  Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/  Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:

Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:  Two people thinking.Photo credit:

Two people thinking.Photo credit:

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

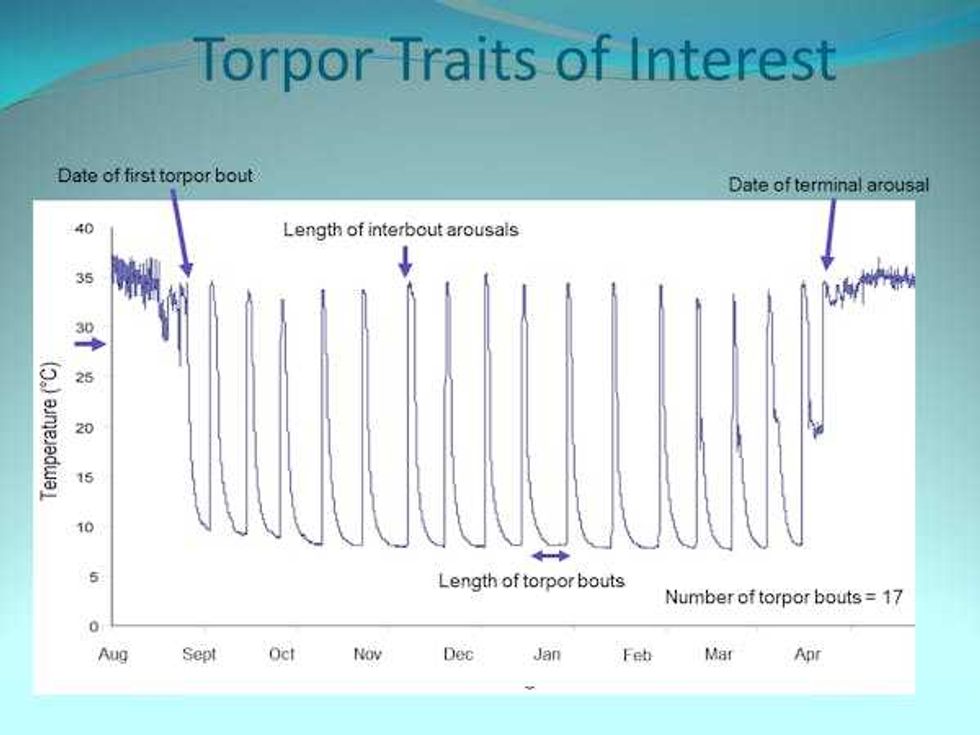

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva  A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

People voting. Photo credit:

People voting. Photo credit:  Young women rally. Photo credit:

Young women rally. Photo credit:  Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/

Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/