The recent cancellation of an appearance by conservative commentator Ann Coulter at the University of California at Berkeley resulted in confrontations between protestors. It’s the latest in a series of heated disputes that have taken place involving controversial speakers on campus.

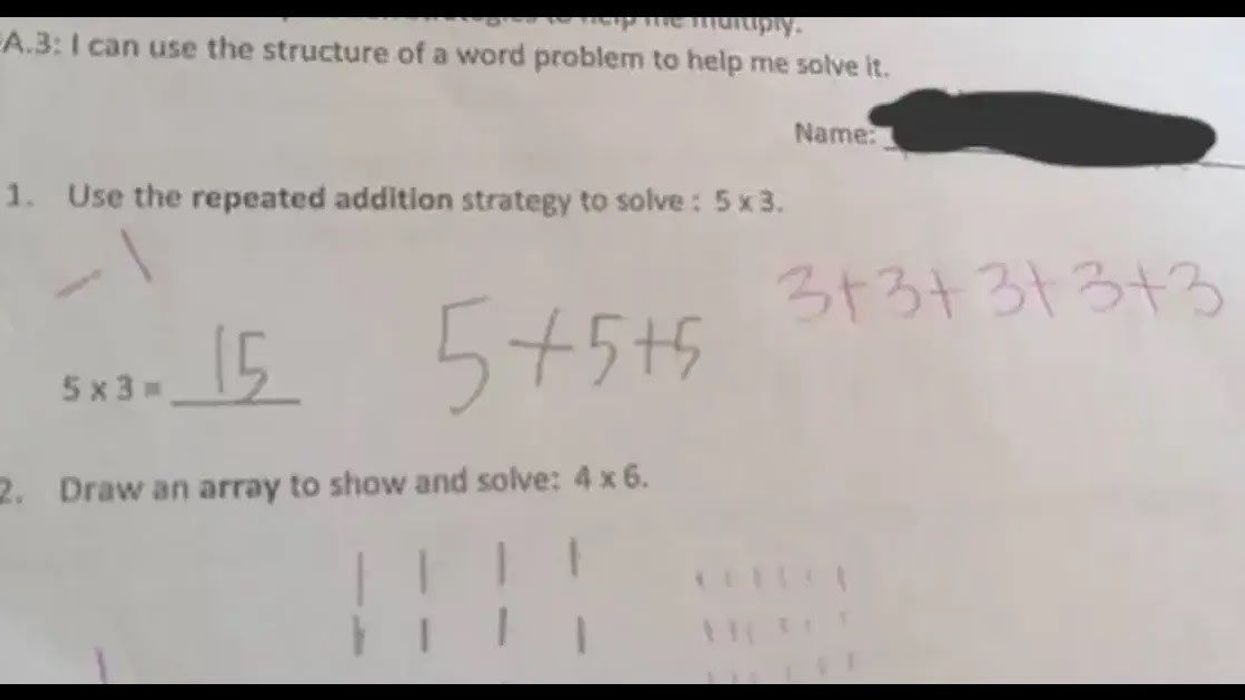

One of us is a researcher of higher education legal issues (Neal) and one is a senior administrator in higher education (Brandi). Together, we’re interested in how institutions facilitate free speech while also supporting students.

From our different perspectives, we see two closely connected questions arise: What legal rules must colleges and universities follow when it comes to speech on campus? And what principles and educational values should guide university actions concerning free speech?

Key legal standards

When it comes to the legal requirements for free speech on campus, a key initial consideration is whether an institution is public or private.

Public colleges and universities, as governmental institutions, are obligated to uphold First Amendment protections for free speech. In contrast, private institutions may choose to adopt speech policies similar to their public counterparts, but they aren’t subject to constitutional speech requirements. California proves a notable exception: State law requires private secular colleges and universities to follow First Amendment standards in relation to students.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Rather than labeling students as fragile ‘snowflakes,’ why not support and engage with them?[/quote]

For those colleges that are subject to constitutional speech rules, what does this mean?

For starters, an institution does not have to make all places on campus, such as offices or libraries, available to speakers or protesters. Universities may also provide less campus access to individuals unaffiliated with the institution, thus potentially limiting the presence on campus of activists or protesters who are not official members of the university community.

Regardless of these limitations on free speech, once an institution categorizes a campus space as accessible for students or permits its use for a specific purpose—such as musical or theatrical performances—campus officials must not favor particular views or messages in granting access.

Some campus areas, such as plazas or courtyards, either by tradition or designation, constitute open places for speech and expression, including for the general public. Colleges and universities may impose reasonable rules to regulate the use of these kinds of open campus forums (e.g., restrictions on the length of the event, blocking roadways, or the use of amplification devices). However, a guiding First Amendment principle is that institutions cannot impose restrictions based on the content of a speaker’s message.

Free speech zones

A central point of conflict over student speech and activism involves rules at some institutions that restrict student speech and related activities (such as protests, distributing fliers, or petition gathering) to specified areas or zones on campus.

Students have argued that such “free speech zones” are overly restrictive and violate the First Amendment. For instance, a community college student in Los Angeles alleges in a current lawsuit that his First Amendment rights were violated when he was allowed to distribute copies of the U.S Constitution only in a designated free speech zone. Virginia, Missouri, Arizona, and Colorado (as of this April) have legislation that prohibits public institutions from enforcing such zones. At least six other states are considering similar laws.

In our view, legislative and litigation efforts may curtail the use of designated free speech zones for students in much of public higher education. In the meantime, increasing resistance could be enough to prompt many institutions to voluntarily end their use.

Beyond legal requirements

While legal compliance is certainly an important factor in shaping policy and practice around free speech, campus leaders should perhaps have a different consideration foremost on their minds: namely, the institutional mission of education.

Most students arrive on our nation’s campuses to acquire a degree, discover who they are, and determine what they want to be. Students grow in myriad ways—cognitively, morally, and psychosocially—while in college.

This personal development cannot fully take place without exposure to opposing views. To that end, students should be encouraged to express themselves civilly, listen to critiques of their ideas, and think deeply about their convictions. Then, in response, students can express themselves again in light of new and opposing ideas.

This process of engagement, productive discourse, and critical reflection can create tension and conflict for many. The reality is that protected free speech is not always viewed as good or productive speech by all members of the campus community.

However, rather than labeling students as fragile “snowflakes” or pressuring institutions to punish students who wish to challenge campus speakers, in our view, there’s a better approach. Why not take seriously students’ objections to controversial speakers—support them and engage with them on how to reconcile their concerns and institutional commitments to free speech?

Free speech issues on campus are often messy and can make both students and campus officials uneasy. But discomfort also presents an opportunity for growth. We believe that educational institutions have a responsibility to foster debate and to help students gain experience in processing and responding to messages they find objectionable.

And so, when controversies arise, campus officials—at times stretching their own comfort zones around issues of student speech and activism—can embrace the educational opportunities they present.

Ladder leads out of darkness.Photo credit

Ladder leads out of darkness.Photo credit  Woman's reflection in shadow.Photo credit

Woman's reflection in shadow.Photo credit  Young woman frazzled.Photo credit

Young woman frazzled.Photo credit

A woman looks out on the waterCanva

A woman looks out on the waterCanva A couple sits in uncomfortable silenceCanva

A couple sits in uncomfortable silenceCanva Gif of woman saying "I won't be bound to any man." via

Gif of woman saying "I won't be bound to any man." via  Woman working late at nightCanva

Woman working late at nightCanva Gif of woman saying "Happy. Independent. Feminine." via

Gif of woman saying "Happy. Independent. Feminine." via

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.