IN HIS PAPER, MY STUDENT HAD WRITTEN “MY BROTHER DEAD.” I circled “dead” and wrote the following note in the margin: “Died. You need a past tense verb here, not an adjective. Your brother died.”

“My mom left and me and my siblings shuffled into the back of a government car to go to foster care,” wrote another. I underlined the first part of the sentence, adding, “My siblings and I.”

Though my curt corrections may seem cruel, they’re exactly what my students need.

I teach College Writing I and II at two colleges. This semester, I taught four classes with a combined total of 88 students. Many of them are immigrants or refugees from other countries, and English is their second, third, fourth, or fifth language. They’ve lived through harrowing experiences—war, extreme poverty, illness, death of loved ones, incarceration—and, at times, they choose to write about these experiences and other topics with deep emotional resonance. And I have to fix their grammar and correct their syntax, while they describe some of the darkest and most challenging times in their lives.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]This semester, I taught four classes with a combined total of 88 students.[/quote]

Of course, I also include encouraging notes and compliment them on having the courage to share their stories and on the beauty of their language. But this doesn’t change the fact that my job requires me to fix words and phrases in a matter-of-fact manner that sometimes breaks my heart. They need to demonstrate that they’ve mastered grammar, syntax, and the concept of the narrative arc in order to succeed in their personal and professional lives (despite recent notable examples of high-profile individuals and organizations lacking such skills). It’s my job to teach them how.

“I works hard to endure it, but happiness isn’t destin for me.” Above this sentence, I scrawled, “Subject-verb agreement problem here. It should read I work hard. Also, I think you mean destined?”

Over my last decade of teaching, I’ve learned that to be a good and effective teacher, I need to maintain a certain distance from my students, their stories, and my own feelings that arise in response to them. In my early years of teaching I had become more involved, offering them support by listening to their problems during office hours, loaning them an old laptop for the semester, connecting them with social services, or giving them bus fare. But just as a good parent is not exactly a friend, a teacher is not a social worker or a licensed therapist, though I sometimes wish I were.

If I were to become emotionally involved in each of my 88 students’ lives and their stories the way I used to, the way I want to, I wouldn’t last in this profession—and I love what I do. In order to teach semester after semester, year after year, to fascinating and resilient people who I’ll never see again, it’s necessary to withdraw some humanity, some natural feeling, which usually rushes back on the last day of class when we hug or shake hands and sincerely wish each other, “Have a good life!”

Even writing extensive comments on a paper can be an occupational hazard. Every student writes several drafts of four multiple page papers. This translates into thousands of pages to read and respond to. In my sixth year of teaching these courses, I’ve had to limit the amount I comment on each paper, and, story after story after story, I’ve gone a bit numb.

Then one afternoon, my false detachment shattered, and we were suddenly 23 humans—hearts pounding, eyes wide, breathing fast—together in a room. In the middle of class, the door flung open and a young man with a large backpack rushed in. (That fall there had been 15 shootings in schools, half of which had taken place in colleges). That fact burned in my mind as I watched him stand there motionless at the front of the class.

My body was electric. My students were silent and still. Would we be the next headline? We were all in clean sweaters and jeans—would we end up bloody pulp like we’d seen on so many broadcasts? I moved toward him from my behind my desk. “I think you’re in the wrong room,” I said.

He stood in the center of the classroom, his mouth slightly open, a glazed look in his eyes, staring straight ahead at the wall. My students’ books were open; some had fingers holding their place on the page, but all eyes were fixed on him. I watched his unmoving body. Would he reach into his jacket? Fling down his backpack? Recognize he’d made a mistake and walk away?

My body was shaking. I moved toward him and the door in an effort to try to usher him out. He stood there a moment longer. “You need to leave,” I said in my most dispassionate voice.

Something in him seemed to wake up. He slowly lifted his right arm and pointed to the back wall, “That’s my coat,” he said. A dark blue jacket hung from a row of hooks I’d never noticed. We all watched as he walked to toward his jacket in a trance, retrieved it, and left.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]One moment you’re correcting someone’s grammar or annotating a paragraph, the next you could be spending your last moments in each other’s company.[/quote]

There was something off about him; he didn’t seem embarrassed, nor did he apologize for interrupting class. When he left, there was a collective release.

“I thought he was going to start shooting us,” one student said.

“I did too,” I admitted. “I was trying to get him out of here.”

Many of us were visibly shaken, and visibly relieved. In this cultural epidemic of mass shootings at movie theaters, schools, restaurants, and concerts, one moment you’re steeped in the mundanities of life (sharing a sandwich, swaying to a song, annotating a paragraph), the next you could be spending your last moments in each other’s company. Like coworkers who held hands on high floors of the World Trade Center—janitor, investment broker, administrative assistant—who flew to their deaths together, or like the clubbers in Orlando, strangers who silently locked eyes for their last seconds of life on the floor of a bathroom stall, strangers become family, the most important people in the final moments of your life.

“He wasn’t saying anything,” a student said, still spellbound. “He just stood there.”

“That dude was high,” said another. “I thought he was about to pass out.”

By the end of the class, we were teacher and student again, and we had finished our task for the day: annotating and analyzing an essay about globalization. They asked questions about that night’s assignment, and I gave them answers. But in my body echoed the feeling of barely avoided horror, of how we almost needed each other desperately, of how we almost became potential heroes, victims, and best friends.

As much as I’d trained myself to turn it off, I deeply felt our common humanity, the vulnerability of our flesh and blood—so much more real than the abstract concept of subject-verb agreement and the other writing rules and techniques that brought us together. As we neared the end of the semester, while I still lectured about tone and grading rubrics, I remember that pregnant moment when time stood still was in the back of my mind.

Now, when grading, I write a few sentences more than I did before. During my office hours, I offer support and advice if a student needs a sympathetic ear. I give out bus fare. I escort a student to the guidance office. I take the time to consider the path a student has taken to stand where he now stands. Even though there are 87 others I need to respond to, this one is unique and aching and triumphant, and I remember how once, we almost became family.

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/  Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/  Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:

Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:  Two people thinking.Photo credit:

Two people thinking.Photo credit:

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

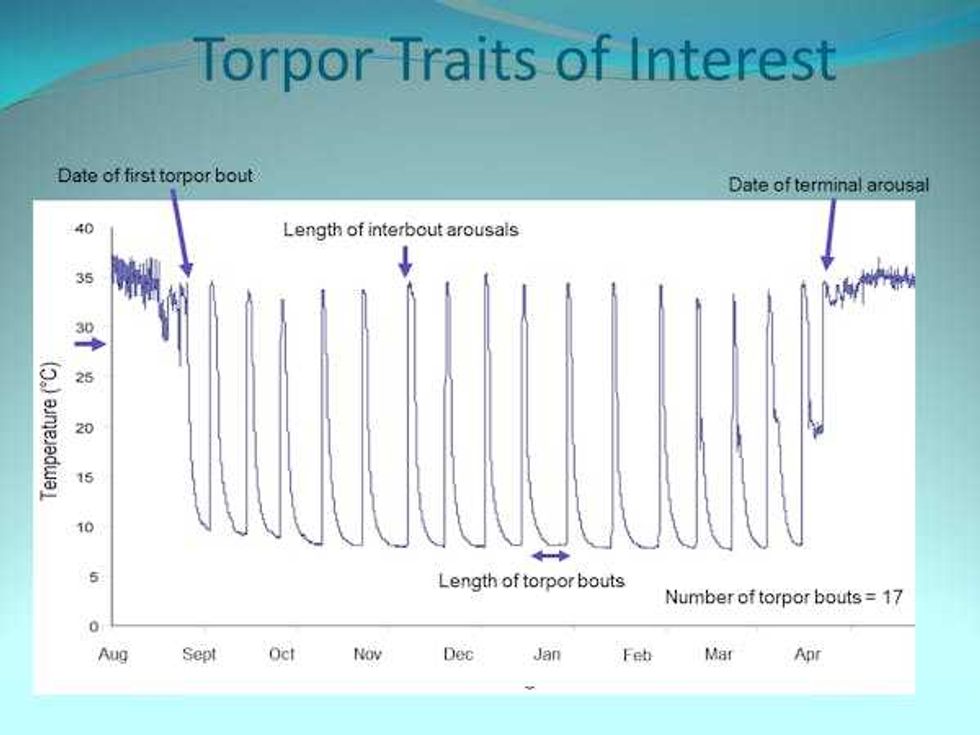

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided