While we were working on this issue, there was an incredible scene on Mike Judge’s Silicon Valley that spoofed the current day cult of failure. In describing the ongoing tribulations of his technology company, CEO Gavin Belson proclaimed: “What those in dying business sectors call failure, we in tech know to be pre-greatness.” He uttered these words in front of a screen that spelled out his point in no uncertain terms: “Failure equals success.” Those listening nodded intently as if Belson were a Zen master.

The idea of failure has been in flux throughout human history. Whether linked to sin (Judeo-Christianity), ignorance (the Enlightenment), or abnormality (modernity), societies have continually propped up distinct notions of failure to bolster corresponding notions of success. But something strange has happened in recent years: Instead of propping up success, failure now seems to be competing with it. Throughout our culture, we find failure being celebrated as if it were a virtue. According to Oprah, it is a “stepping stone to greatness.” J.K. Rowling claims that it comes with “fringe benefits.” And all over the business world, it is positioned as the unmistakable key to unlocking human excellence. “It’s fine to celebrate success,” remarked Bill Gates. “But it is more important to heed the lessons of failure.”

This issue of GOOD aims to dig at the roots of the curious cause célèbre—failure. To this end, we invited a group of creative change-maker types to dinner to discuss how the failure/success binary can prove confounding in the civic space (“The GOOD Dinnertime Conversation”).

In new fiction from Lara Vapnyar, we see that the same binary that undermines organizations can also undermine individuals, as witnessed by a relationship crushed by unrealistic notions of success (“Buddha’s Hand”).

Is the entire failure and success conversation the product of an exaggerated sense of individual power? So suggests Amanda Fortini, who captures a form of rural life so jarring that it recalibrates a sense of self in need of balance (“The Great Surrender”).

Vervey, Switzerland-based “idea factory” Riverboom takes a look at the other side of that coin, prodding us to wonder whether a landscape so lush and bountiful as that of the Tour of Italy (Giro d’Italia) inflates our sense of individual power to unhealthy degrees (“Eyes on the Prize”).

Finally, we present Winston Struye’s incredible photo project with the Nepali youth of the ROKPA Children’s Home in Kathmandu, which captures stories of resilience that otherwise eluded the international media (“Our City is Devastated. We Are Not.”). Despite the devastation of the quake, the photos point to a psycho-spiritual success from which we can all draw strength.

It strikes me as mildly significant that the cultural conversation about the power of failure generally ballooned around the time of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the reign of George W. Bush, the bursting of the housing bubble—banks that were “too big to fail”—and the global financial crisis. What if we have embraced failure, in part, as a coping mechanism for these high profile breakdowns? In this issue we ask whether the cultural pendulum has swung too far from success to failure and whether, in the parlance of global markets, we are now in need of a correction. If that’s the case, perhaps this can be a start.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Leonard Cohen performs in Australia in 2009.Stefan Karpiniec/

Leonard Cohen performs in Australia in 2009.Stefan Karpiniec/  Enjoying a sunset.Photo credit

Enjoying a sunset.Photo credit

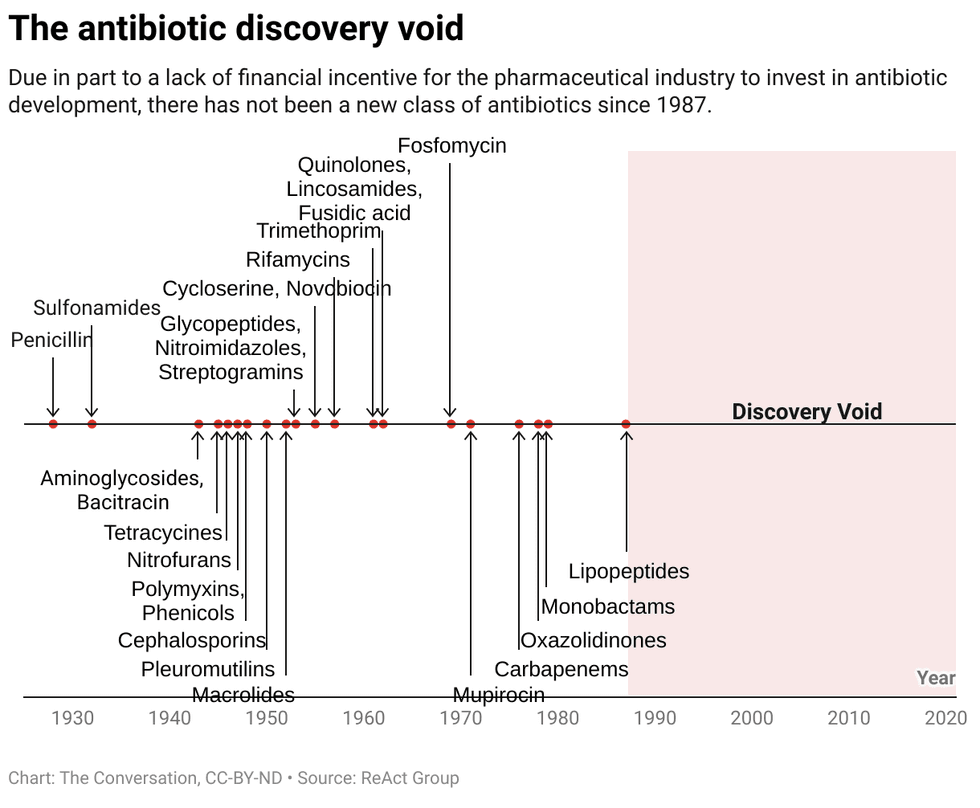

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

An envelope filled with cashCanva

An envelope filled with cashCanva Gif of someone saying "Oh, you

Gif of someone saying "Oh, you

Two penguins play by the waterCanva

Two penguins play by the waterCanva