It’s a balmy night as Jónathan Cebreros glides across the outdoor stage to the dramatic pulse of Verdi’s La Traviata, joining two elegantly dressed sopranos, his own smooth, powerful tenor building, rolling, and reaching over the swelling audience in Italian. Ah, yes! Let’s enjoy the wine and the singing, the beautiful night, and the laughter. Let the new day find us in this paradise, he sings.

And the joyous night does feel like a kind of paradise, albeit an unexpected one. This alfresco opera is not being held in an arts epicenter like Rome, New York, or Paris, but along the California-Mexico border in rough-edged Tijuana. There are no elevated boxes for VIP guests, no black-tie-preferred dress code, no ornate auditorium filled with red velvet seats. Here, locals young and old, families and students, fill rows of red plastic seats on one of Tijuana’s wide streets, spilling over onto the sidewalks, mesmerized by the grand voices booming from the stage as they put their arms around their abuelitas or niños and sip slushy granitas or beer. This is the 12th year of Opera en la Calle, Tijuana’s free Opera in the Street festival, held every year in one of the oldest, working class neighborhoods in Tijuana: Colonia Libertad. The hilly neighborhood is nestled alongside the border, its dense streets jam-packed with small houses, some boasting quaint gardens, some with protective spikes, and some sporting both. It has been the home of boxers, gangsters, mayors, artists, and immigrant smugglers—but Tijuana’s notorious narrative of drug violence and crime has waned over the past decade, making way for Tijuana’s growing middle class to enjoy an increasingly sophisticated nightlife. Just seven years earlier, rampant violence infiltrated bars and cafés, seeping onto the streets. Today, there are an estimated 12,000 Tijuananese from all over the city gathered to observe Italian opera with a side of tacos de mariscos.

Backstage, as performers don gold masks and musicians hoist and tune their instruments, Tijuana Opera general director María Teresa Riqué pauses to reflect on what events like these mean to the community. “It’s been very important for the people because they feel like we are pointing our attention to them,” Riqué says. “Opera has been considered just for the high classes, and we have broken that taboo.”

A few hours before his performance, Cebreros is hanging out at the beachside Café Latitud 42 in Tijuana’s Playas neighborhood where he grew up. “There’s no other place in Mexico that has a festival like it,” Cebreros says between sips of coffee as deep blue Pacific waves crash nearby. “We want opera for everyone! That’s what we do.” He adds on, “It’s an opportunity to experience a very complex art form as a community.”

Cebreros appears kind and intelligent, with a thoughtful manner of speaking that stretches beyond his 26 years. He waxes poetic about Tijuana’s craft beer boom and the New York Times-approved Baja Med cuisine that has taken hold in the city. His hometown pride is apparent, though he wistfully jokes about retiring in Austria due to a deep love of Salzburg (Mozart’s birthplace) and Vienna’s many museums.

Despite his passion for opera and culture now, Cebreros insists he wasn’t always enamored with the arts. His father is a roofing contractor in Tijuana, his mother a housewife. The youngest of four, Cebreros says no one else in his family is musically inclined. In fact, it wasn’t until he was forced into choir his senior year of high school (it was the only class that would fit his busy academic schedule) that he discovered his love of music. There, his choir teacher, who also worked for the Tijuana Opera, introduced the class to Messiah, composer George Frideric Handel’s renowned Baroque-era opera, and Mozart’s The Magic Flute, among other classics.

“That’s when I became really amazed about how someone human can produce something that sounds humanly impossible,” Cebreros remembers. “And that’s when I thought, ‘Wow, I want to do this. I would love to do this, just for the heck of it, not even as a profession.’ ”

At age 18, without any formal training, Cebreros was accepted into the Tijuana Opera’s chorus, where he worked tirelessly on his craft and steadily gained more visible roles. He went on to attend nearby San Diego State University, where he studied business and finance. “I actually wanted to double major in music. But the problem was, with the budget crisis in the state of California, no one was allowed to double major,” Cebreros explains. “So, I just took lessons with a teacher there, and I took languages privately. The basics in opera are German, French, Italian, and English.”

Initially, his parents were opposed to the idea of their son making a living in music, but they made a deal that once he finished his degree, he could pursue singing. After undergrad, Cebreros left the beaches of Baja for the world-renowned Chicago College of Performing Arts at Roosevelt University, where he graduated in 2014 with his masters of music in voice and opera. And while he currently works as a business consultant in San Diego, Cebreros continues to rise in the professional opera world.

“As time passed and I got to perform in different settings, I came to realize that artists have a big responsibility and duty to society in general,” he says. He fondly remembers a time when his singing was able to offer solace to cancer patients at a Chicago hospital—drawing an old man out of his room who didn’t walk much due to his chronic pain. “There is a reason for it other than the mere personal joy of performing,” he insists, the emotional response Cebreros is able to draw out of his audience seemingly tantamount to his individual connection with the art form.

“He gets better and better,” says José Medina, the Tijuana Opera’s artistic director who gave Cebreros his first role. This fall, Cebreros has landed a small part with Los Angeles’ critically acclaimed, experimental opera company, The Industry, where he will take part in Hopscotch, an 18-car opera performance on wheels. After that, he will be singing the lead role in Il Cappello di Paglia di Firenze with Point Loma Opera Theatre in San Diego.

“Years ago, we didn’t have the number of performers and singers that we have now in Tijuana,” Medina says, pointing out Cebreros as a testament to the deepening talent pool. He adds that Tijuana is a complex city, and people often only hear the bad news coming out of the border town.

To be sure, Tijuana still hasn’t bucked the unsavory parts of its reputation. The same month of the Opera en la Calle festival, Tijuana is in the news for $11.5 million and 600 rounds of ammunition, likely tied to drug trafficking, seized en route from Tijuana to Mexico City in a truck supposedly carting strawberries. The city is nuanced, locals insist—a place of many diverging cultures, perhaps known more for vice-seeking debauched American tourists, pharmacies, and assembly building factories, but also boasts a blossoming arts scene. And Opera en la Calle has been part of that catalyst. As Medina points out, there’s a hunger for music and culture in a city that doesn’t want to be defined by the “bad stuff.” To Cebreros, Tijuana is a rebel city. “It helps you break structure—you are more spontaneous, in a way,” he says, remembering times when violence was so bad that he and his friends didn’t venture much outside their homes, but they learned to make the most of their situations and not dwell on the negative.

Back at the festival, Cebreros strides in a commanding circle around the stage, his sweet persona from the café suddenly transformed into a confident Casanova. The audience is sardined shoulder-to-shoulder, ensnared in the rich vocal display, the children especially transfixed, as if they might be imagining themselves onstage one day—just as Cebreros once did. It feels warm, hopeful.

Once off stage, Cebreros is beaming, later telling me: “These kinds of moments remind me that the sacrifice…to be an artist makes everything worth it.”

Volunteers at the St. Francis Inn pray together before serving a meal on July 19, 2021.

Volunteers at the St. Francis Inn pray together before serving a meal on July 19, 2021. Police close down a section of Kensington Avenue to clear a homeless encampment on May 8, 2024.

Police close down a section of Kensington Avenue to clear a homeless encampment on May 8, 2024.

Left: A robotic arm. Right: Rice grains.Photo credit:

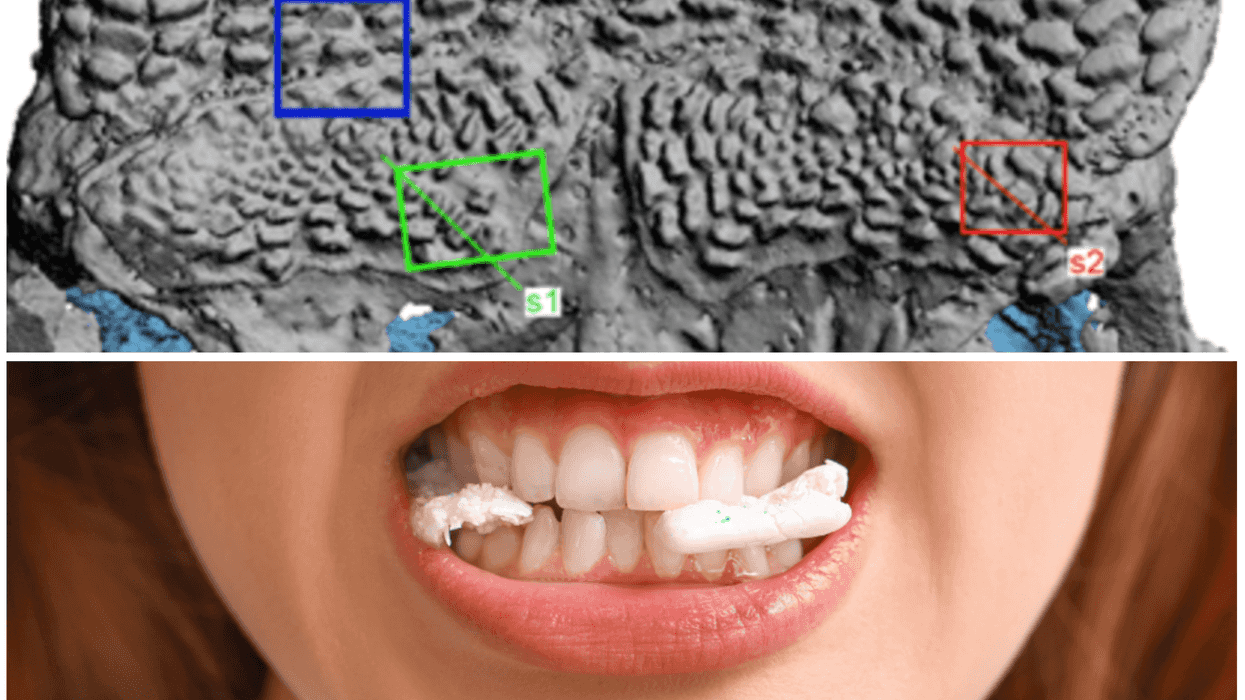

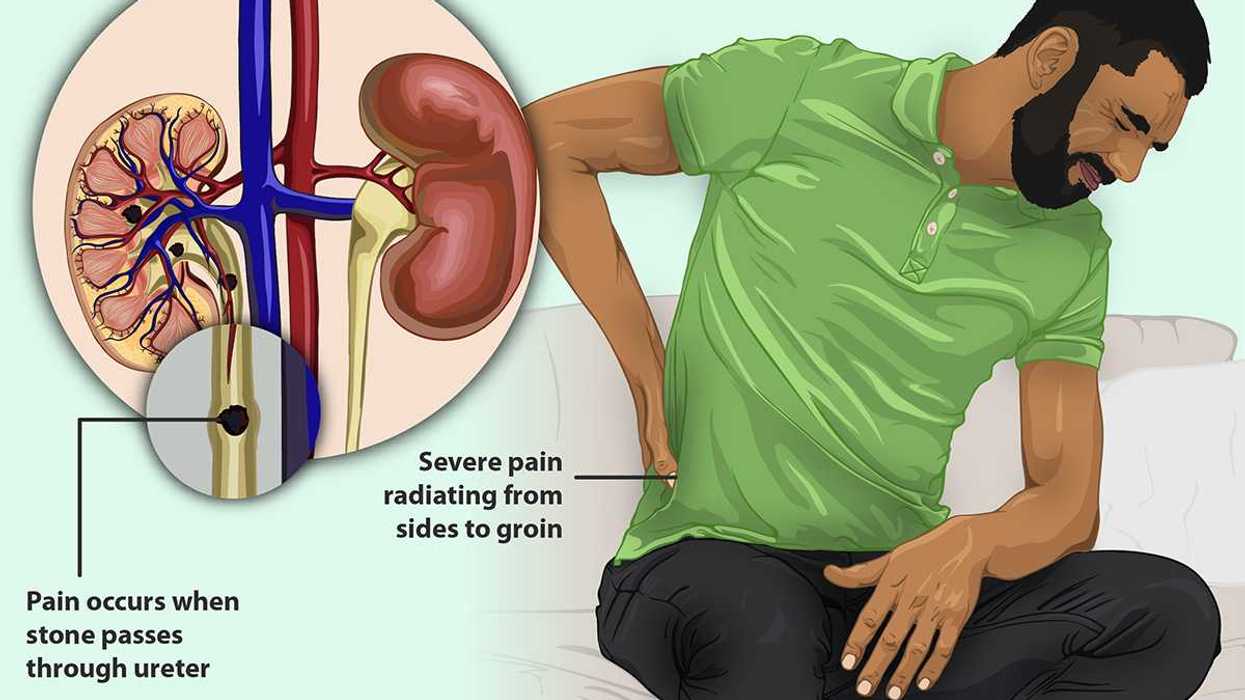

Left: A robotic arm. Right: Rice grains.Photo credit:  A diagram on kidney stones.myupchar/

A diagram on kidney stones.myupchar/

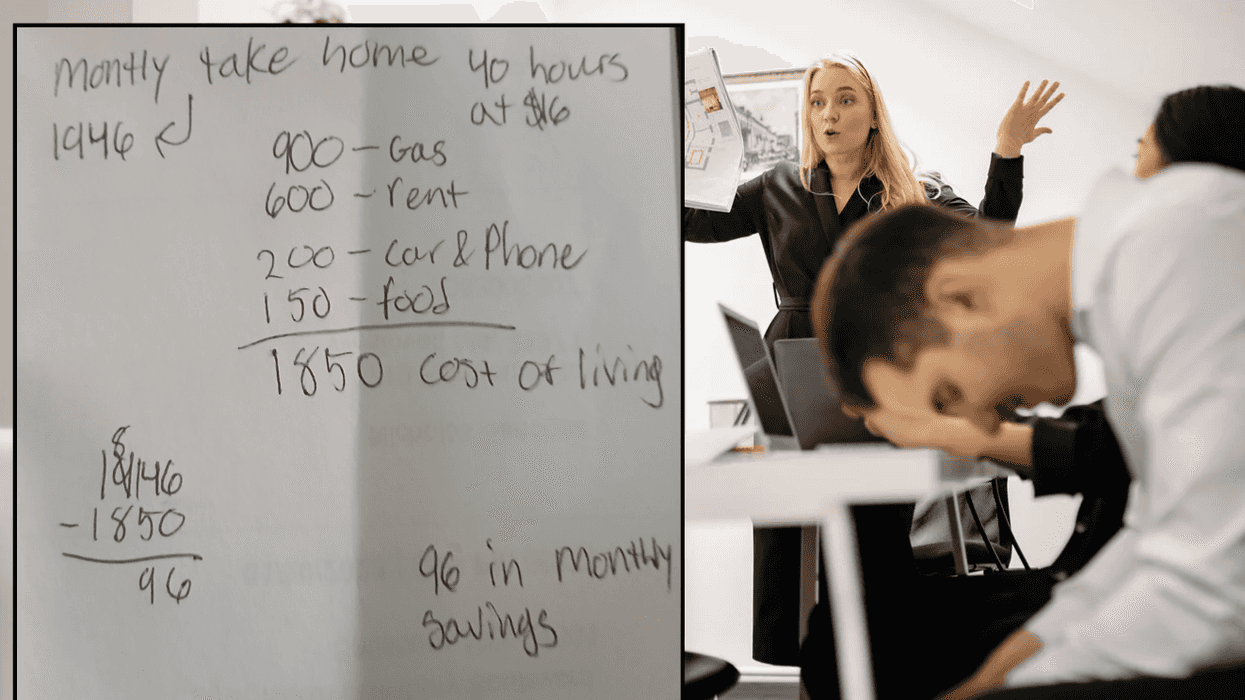

A young person doing their monthly budgetCanva

A young person doing their monthly budgetCanva

A couple engages in a serious conversationCanva

A couple engages in a serious conversationCanva

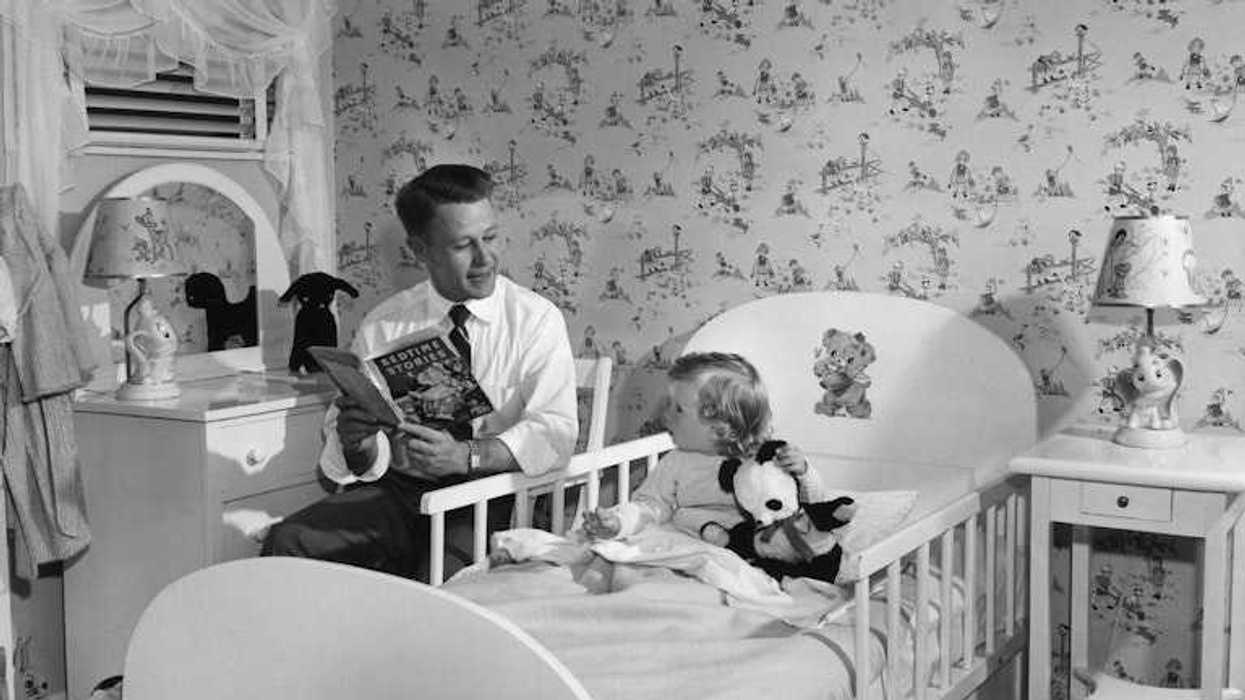

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025.

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025. Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.

Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.