Few things are the subject of fiercer fights than food. In our new series “Food Wars,” we’re going to the front lines of the dishes and debates that matter most. This week, writer Saidat Giwa-Osagie explains why this pan-African dish inspires fierce debate, accusations, and the occasional Hillary Clinton meme.

Here is a recipe ripe for dissent. Take a popular one-pot dish, add millions of West-Africans into the mix, and watch as a heated contest simmers over one question: Which country’s dish reigns supreme?

Jollof rice, darling of West Africa, is the crowd-pleaser that just can’t please everyone. A tantalizing fusion of blended tomatoes, onions, scotch bonnet peppers and rice are the basic building blocks. However, it’s not just its savory spiciness that sets it apart. Jollof’s duality as an emblem of both national and pan-African pride makes it a source of never-ending debate. Though I am partial to several versions of the dish, I am just one voice out of 290 million West Africans and counting.

[quote position="full" is_quote="false"]When Jamie Oliver made the unheard-of additions of lemon and parsley, the controversy was quickly dubbed ‘Jollofgate.’[/quote]

A sprawling West-African diaspora means the debate has gone global. If Helen of Troy caused a thousand ships to set sail with her beauty, then Jollof rice is her culinary equivalent. Inspiring thousands of tweets to bid battle in the name of #jollofwars, the favorite rice dish has many willing defenders. The hashtag is the digital manifestation of the playful rivalry between different West-African countries, and the fight rarely lets up.

Jollof’s derivative origins contribute to the debate of which version is the best. Each country’s take represents a unique slant on the dish. Jollof originates from the Wolof people of Senegal and Gambia, which was an ancient empire spanning the 14th to 19th century. However, historian James McCann notes the far-reaching influence of the dish may be due to a form of “cultural dispersion.” Through this form of dispersion, it is thought that the recipe became popular in different regions and women within those areas used locally available ingredients to put their own spin on the dish.

As the recipe travelled through people to different countries, it evolved in a unique way, characteristic of the locale it had reached. In Liberia, shrimp is added, while in Senegal, a mixture of vegetables and fish makes the dish. It is thought that Jambalaya—a New Orleanian dish composed of rice with a mix of meat, fish and vegetables—is a distant derivative of Jollof.

Comparisons between versions, however, are highly contentious. On a recent trip to Nigeria, Mark Zuckerberg sampled the dish and lightheartedly recounted how he was told not to compare Nigerian Jollof to any other country’s. Earlier this year, Ghanaian singer Sister Deborah released her food-inspired diss track, “Ghana Jollof”, which was met with a mixture of laughter and annoyance. The song extols the virtues of her nation’s version and simultaneously pokes fun at Nigeria’s rice.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=IGEr7TQA2eQ

Then, there are the memes —humorous takes infused with unexpected pop-culture relevance. #Jollofwars is a means for digitally attuned generation to playfully roast one another and competitively flex in the name of national pride. A snapshot of just 1500 #jollofwars tweets have reached over 432,000 Twitter users. The hashtag is one of the ways the digital diaspora is having this debate. #Jollofwars spans beyond West Africa, with fierce arguments coming from diasporic countries including the U.S.A., South Africa, the U.K. and more.

Even though there is little agreement on the best version of the Jollof online or off, there’s a shared emphasis on the importance of preserving the cultural hallmarks and culinary traditions of the recipe as it pertains to each country, despite its many “original” versions. At the same time, there is an accepted level of creative freedom dictated by personal taste. For instance, the spiciness of the rice may change depending on the cook, or the audience. Some cooks might add red peppers for richer color, or prefer to use one type of rice over another. Such quirks can lead to further debate, but they’re both allowable and expected.

Jollof is not a rigid recipe with precise measurements; it’s a recipe of experience, cooked with the eyes as much as it is with the heart. But any attempt to reinvent Jollof without careful consideration of its context is taken seriously and immediately shot down and labeled a form of cultural appropriation.

When celebrity chef Jamie Oliver tried his hand at the dish with unheard-of additions of lemon and parsley, the controversy was quickly dubbed “Jollofgate”. The recipe drew 4,500 comments, with many complaining about the lacklustre nature of the dish. The African blogger who goes by Motely Musings wrote: “How can you gentrify Jollof rice to the extent that it starts looking like paella? Sacrilege!”

Though Oliver’s representative tried to calm the furor by stating the recipe was the chef’s “twist”, it was perceived as an inaccurate depiction of the dish. UK supermarket chain, Tesco, had to remove its Jollof rice recipe from its website after many complained of the dish’s inauthenticity, due to its lack of rudimentary Jollof sauce. After all, what gives Jollof its orange color, except its tomatoey and pepper-infused base? Instead, the recipe substituted the sauce with chopped bell peppers, and was met with ire on social media.

Recent food trends have inspired Jollof variations such as Jollof bulgur and Jollof cous cous. In London, Nigerian pop-up restaurant “Chukus” is even serving Jollof quinoa. Torn between a devoted love of the traditional rice dish and my strong curiosity, I have yet to sample the superfood spin-off. However, diners have flocked to the dish, and lauded it for adding flavor to a health-conscious alternative.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]How can you gentrify Jollof rice to the extent that it starts looking like paella? Sacrilege![/quote]

Sure, as a dish known for reinvention, Jollof rice is subject to transformation—but whether it’s among West-African countries or internationally, such reinvention requires delicate care. Despite its tendency to stir debate, Jollof rice is actually a highly effective pan-African unifier. From personal experience, if there’s a gathering hosted by a Jollof-loving host, the dish is an anticipated highlight; though contentious, appreciation for Jollof is part of an appreciation for life’s big events. It even has its own celebratory day: August 22, 2016 marked the second ever World Jollof Rice Day.

At surface-level, the argument about which country has the best Jollof could be taken as typical neighborly rivalry, but behind the squabbles are a rich tapestry of West African history and culture. Jollof’s richness in flavor is only superseded by the passion of its staunchest fans. Though the argument rages on, there’s almost one thing that’s universally agreed on: get to the party before the Jollof is gone.

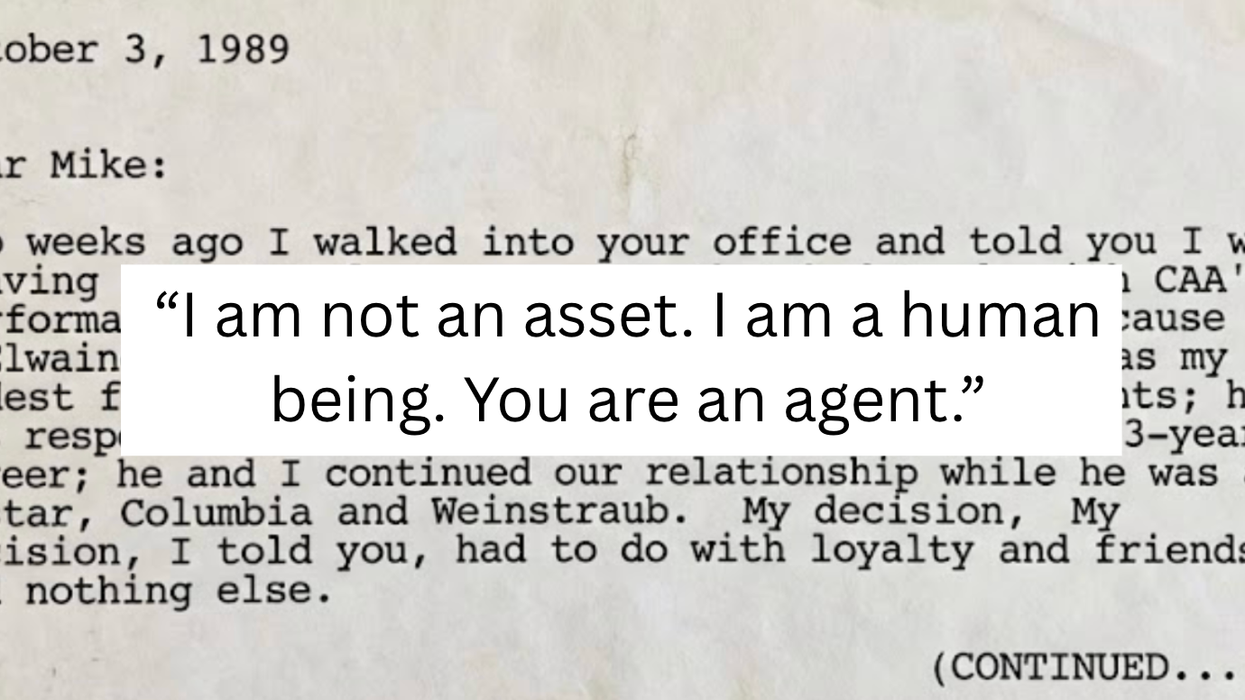

Robert Redford advocating against the demolition of Santa Monica Pier while filming "The Sting" 1973

Robert Redford advocating against the demolition of Santa Monica Pier while filming "The Sting" 1973

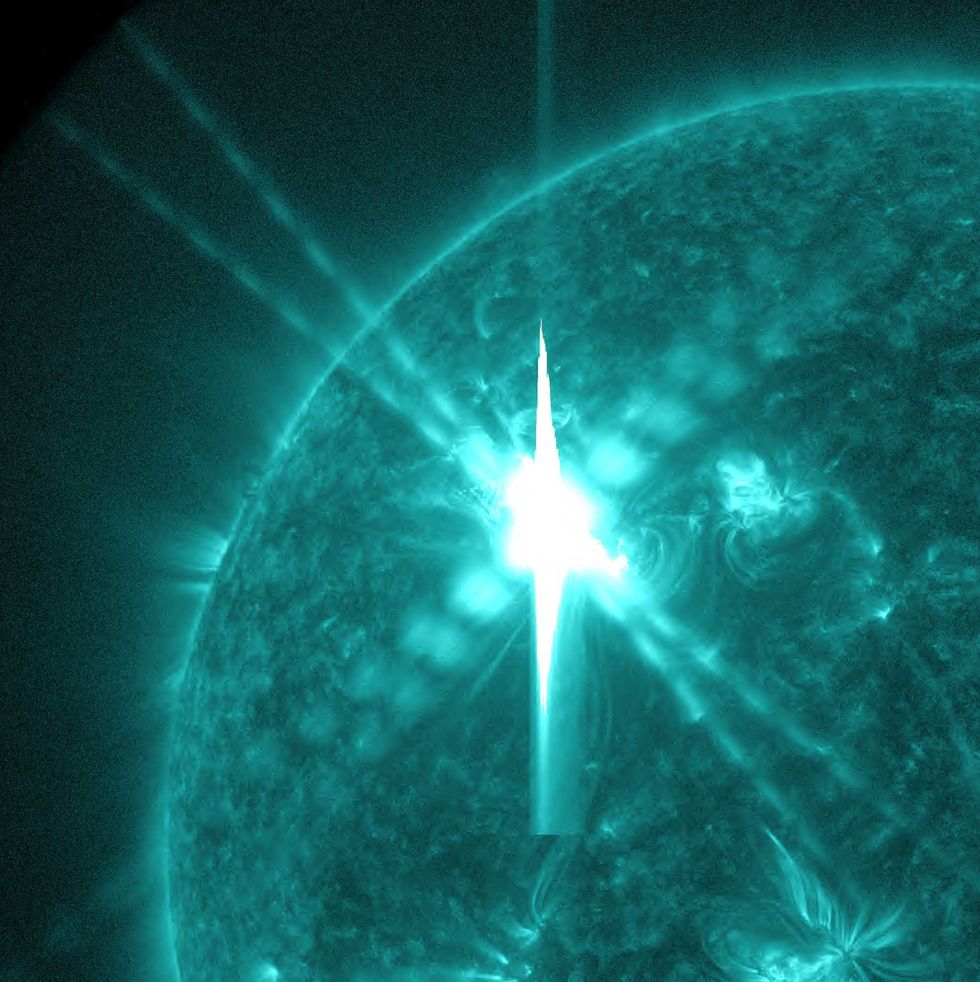

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Ladder leads out of darkness.Photo credit

Ladder leads out of darkness.Photo credit  Woman's reflection in shadow.Photo credit

Woman's reflection in shadow.Photo credit  Young woman frazzled.Photo credit

Young woman frazzled.Photo credit

A woman looks out on the waterCanva

A woman looks out on the waterCanva A couple sits in uncomfortable silenceCanva

A couple sits in uncomfortable silenceCanva Gif of woman saying "I won't be bound to any man." via

Gif of woman saying "I won't be bound to any man." via  Woman working late at nightCanva

Woman working late at nightCanva Gif of woman saying "Happy. Independent. Feminine." via

Gif of woman saying "Happy. Independent. Feminine." via

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.