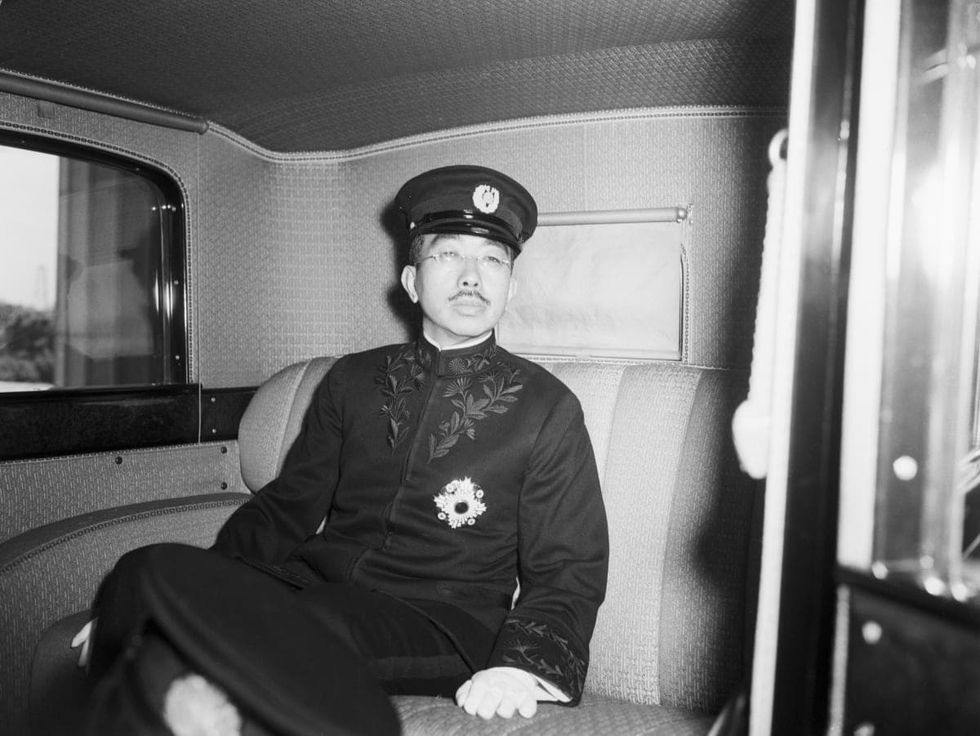

In August 1945, WWII was ravaging the planet. So, to bring an abrupt end to the fighting, the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Tens of thousands of people lost their lives. Japan formally surrendered, as announced by Emperor Hirohito in a broadcast speech in which he asked people to “endure the unendurable and suffer what is unsufferable.” Amidst all this, there was one Japanese soldier who refused to believe that the war had ended.

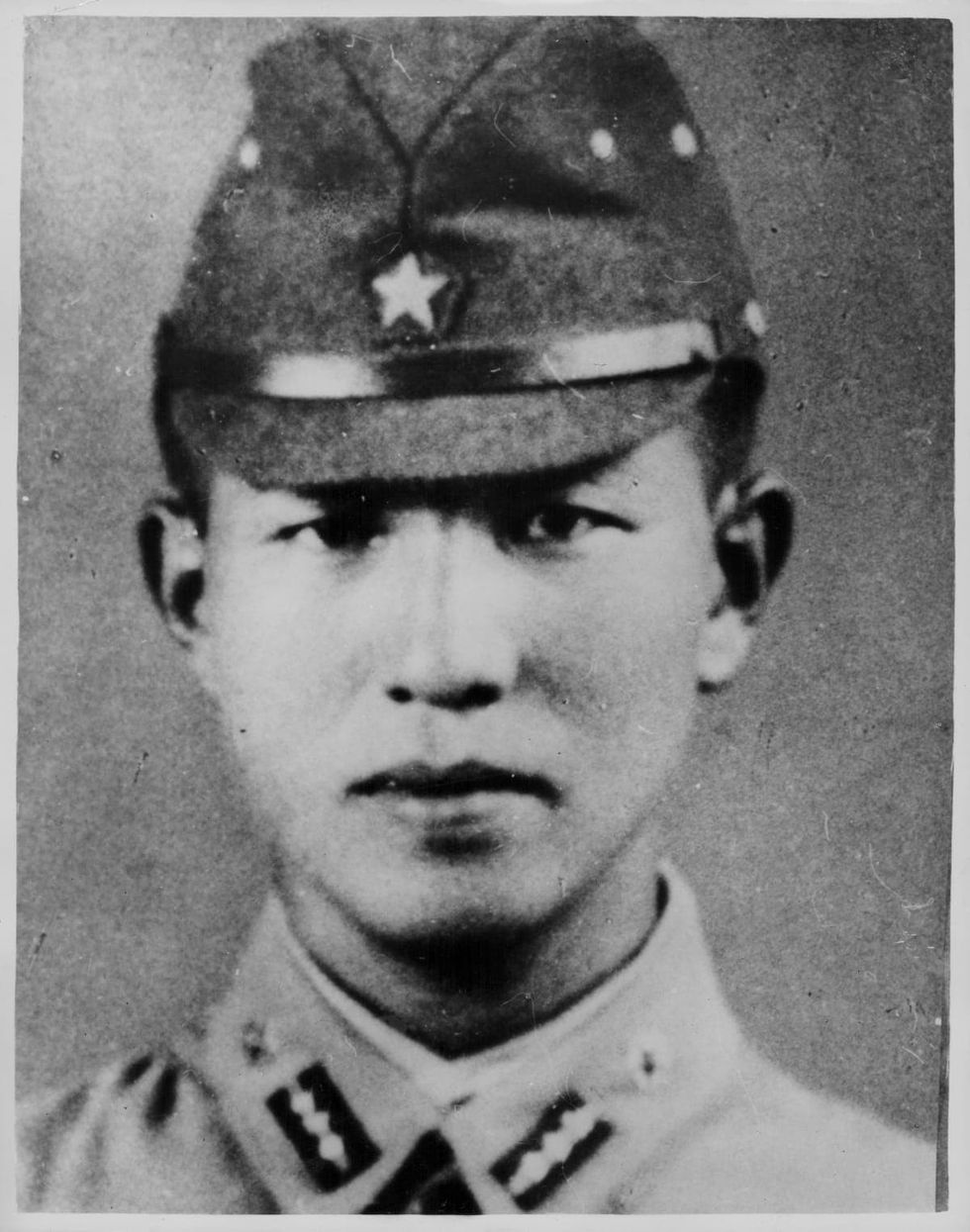

Hiroo Onoda, a native of Wakayama prefecture, was an intelligence officer of the Imperial Japanese Army. Despite the war’s hostile environment culminating to a close, Onoda still stalked the Lubang island of the Philippines, committed to watching the skies for American bomb blasts while surviving on coconut milk, bananas, and slabs of meat that he would cut off the cows he butchered.

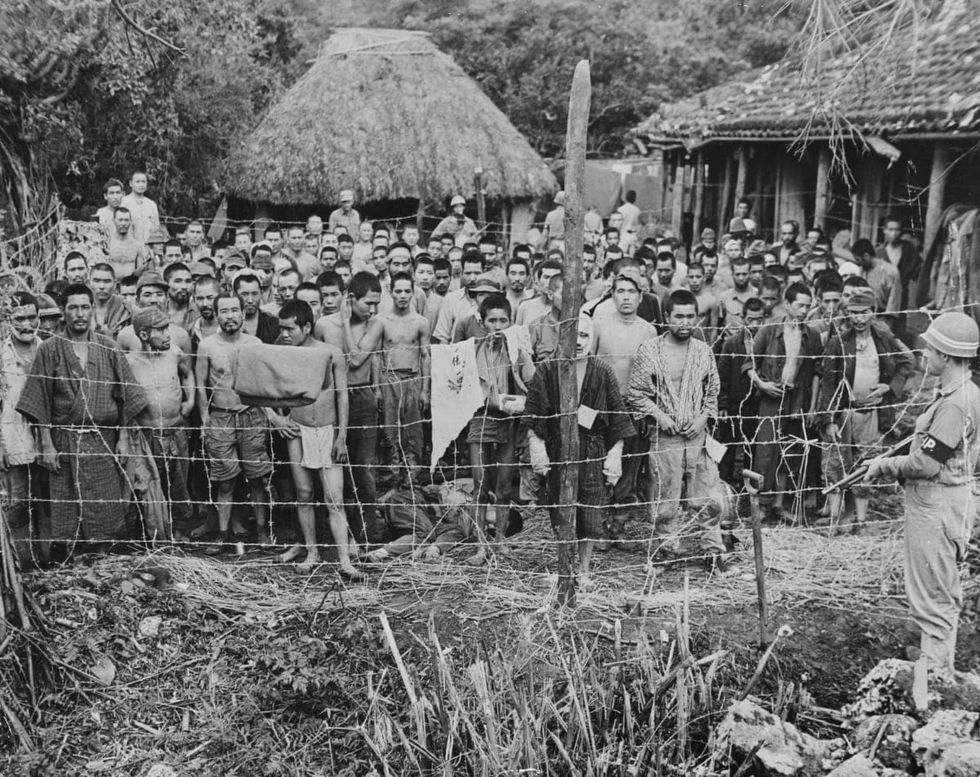

Caught in a time warp, the Japanese holdout soldier hunkered for 29 long years in the Philippine jungles, after World War II, initially with three comrades and then alone after the two soldiers died in clashes with Filipino villagers and soldiers. Denying Japan’s surrender, he reckoned that it was just propaganda.

Standing firm in his mission, Onoda continued his training in guerilla warfare and killed nearly 30 civilians whom he mistakenly believed to be enemy soldiers. As time floated by in a haze, he blatantly ignored all attempts to get him to surrender. He dismissed leaflet drops and search parties thinking it was a deception of the enemy. "The leaflets they dropped were filled with mistakes, so I judged it was a plot by the Americans," he told ABC.

One day, he was walking by a road and noticed something that made him sad about the war, “On the way, I saw American chewing gum wrappers by the side of the road. In one place a wad of chewing gum was sticking to the leaf of a weed. Here, we were holding on for dear life, and these characters were chewing gum while they fought! I was more sad than angry. The chewing gum tinfoil told me just how miserably we had been beaten,” Onoda wrote in his book “No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War.”

"Every Japanese soldier was prepared for death, but as an intelligence officer, I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die," he told the ABC four years before his death in January 2014, at the age of 91. "I became an officer and I received an order. If I could not carry it out I would feel shame. I am very competitive."

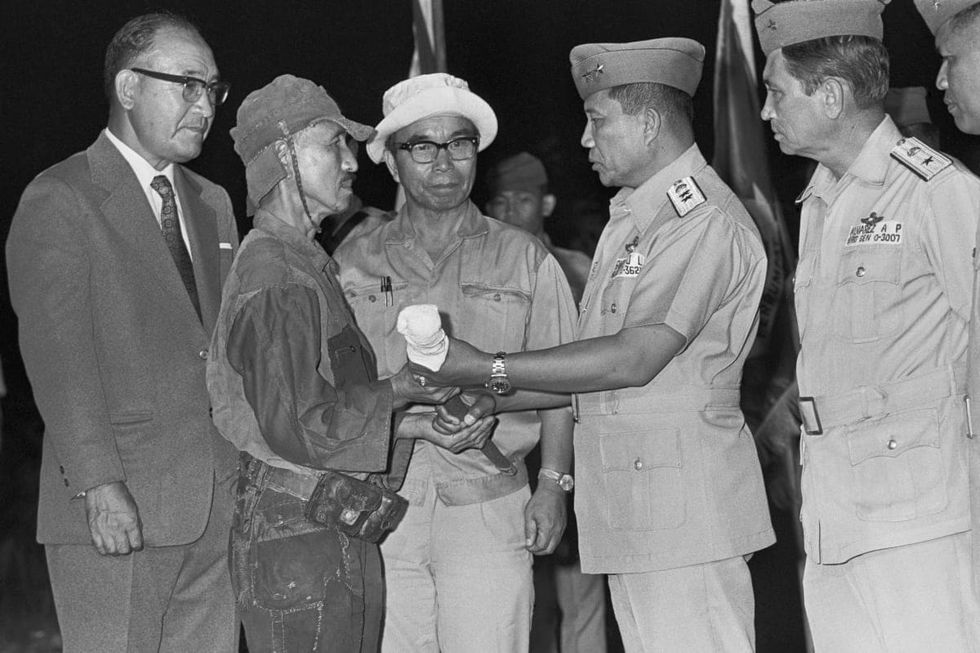

In 1974, when a Japanese commanding officer and adventurer located him and relayed the message that the Emperor wanted him to return to Japan, he had no choice but to lay down his arms and return. In his homecoming to Japan, Onoda was bestowed the prestige of being seen as a hero. He stepped up to second lieutenant in the Imperial Japanese Army and authored several books about his experiences.

When Onoda surrendered, the Philippines government forgave him for his involvement in the killing of the thirty islanders. He too extended generous donations towards the island people, in the form of musical organs, school supplies, crayons, pencils, and more, when he visited there in the early 1990s, ABC reported.

Lubang even developed a tourist attraction called the “Onoda Trail” in 2010, inspired by Onada’s adventures in his jungle stronghold. Onoda Trail is a network of pathways that Onoda and his fellow soldiers took to escape their enemies. The trail extends from Barangay village in Lubang to the neighboring Looc town, a loop of about 8 km.

In 1975, Onoda emigrated to Brazil where he worked as a cattle breeder on a ranch. In January 2014, he died of heart failure at a Tokyo hospital. Officials from Lubang Island sent their condolences to him.

Onoda’s distinguished story was documented in Arthur Harari’s 2021 narrative feature “Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle,” which was also screened at Cannes. His story also makes the main theme of Werner Herzog’s 2022 novel, “The Twilight World.”

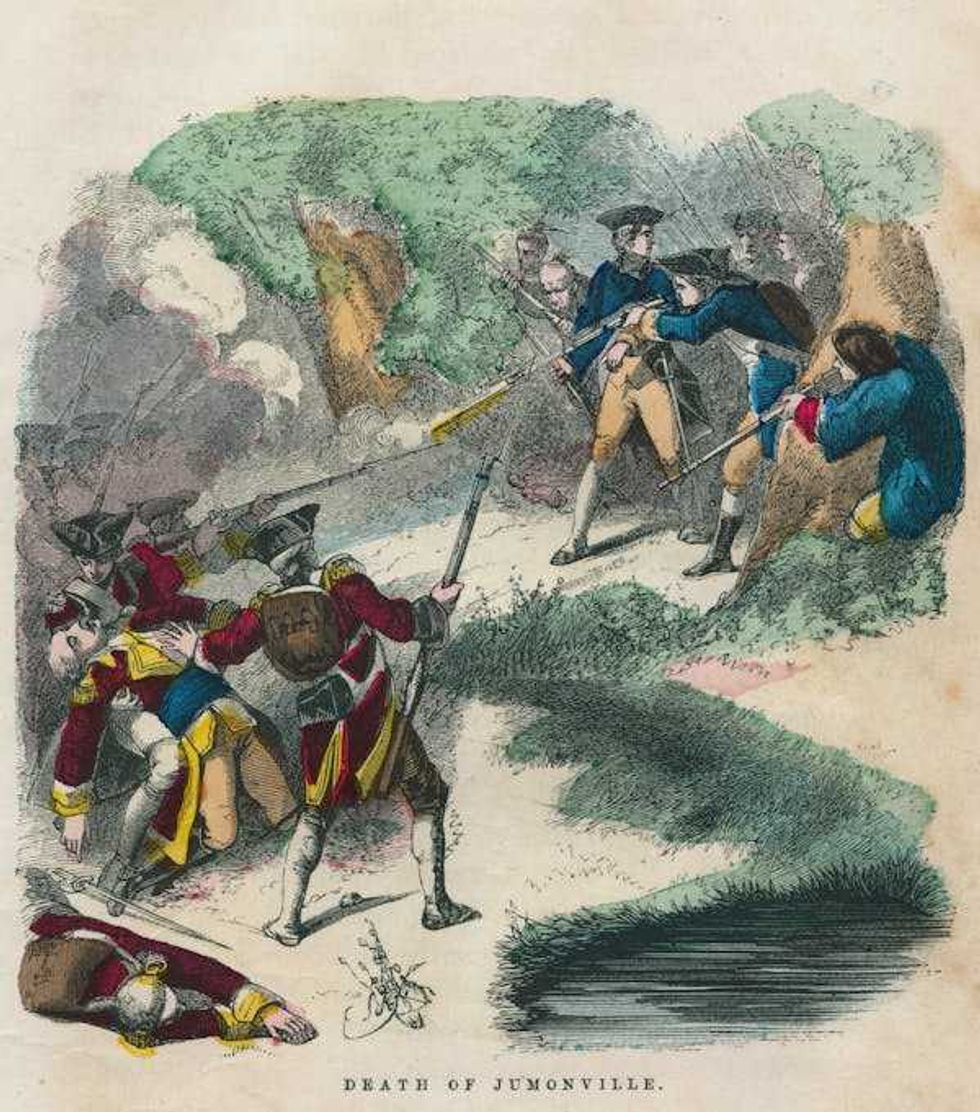

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War.

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War. Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity.

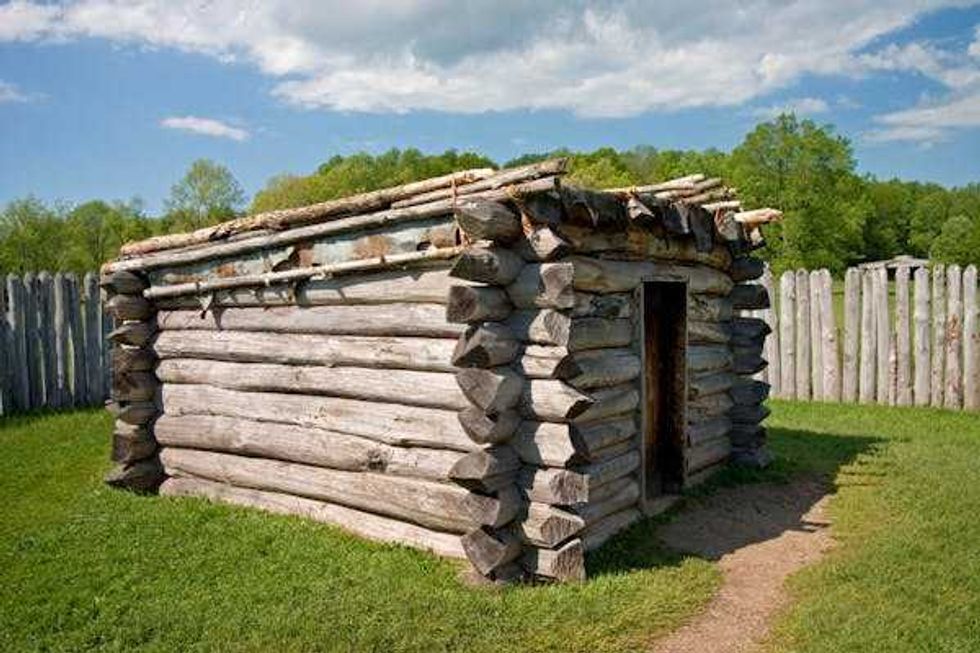

Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity. A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

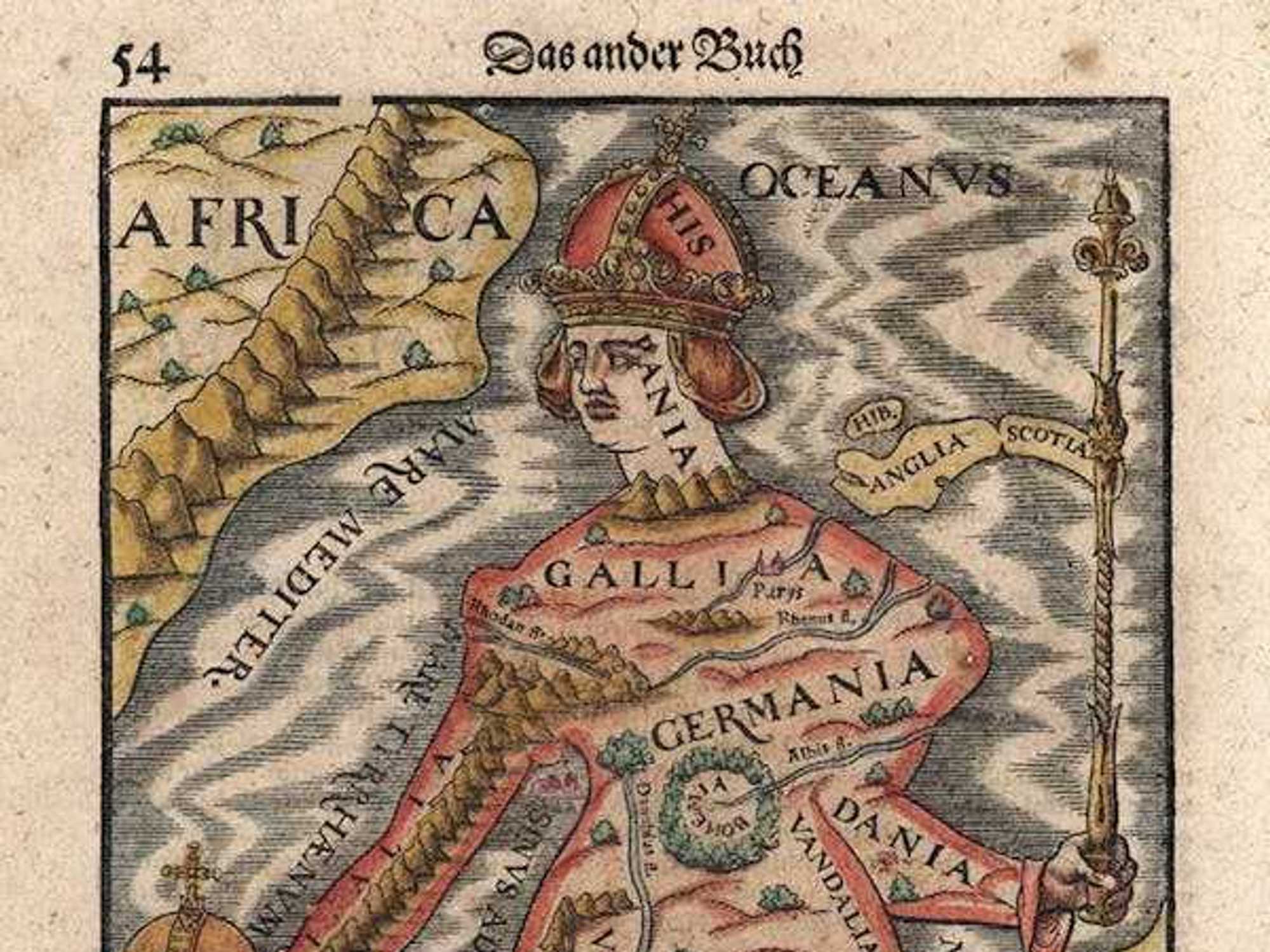

Europa Regina (1570).

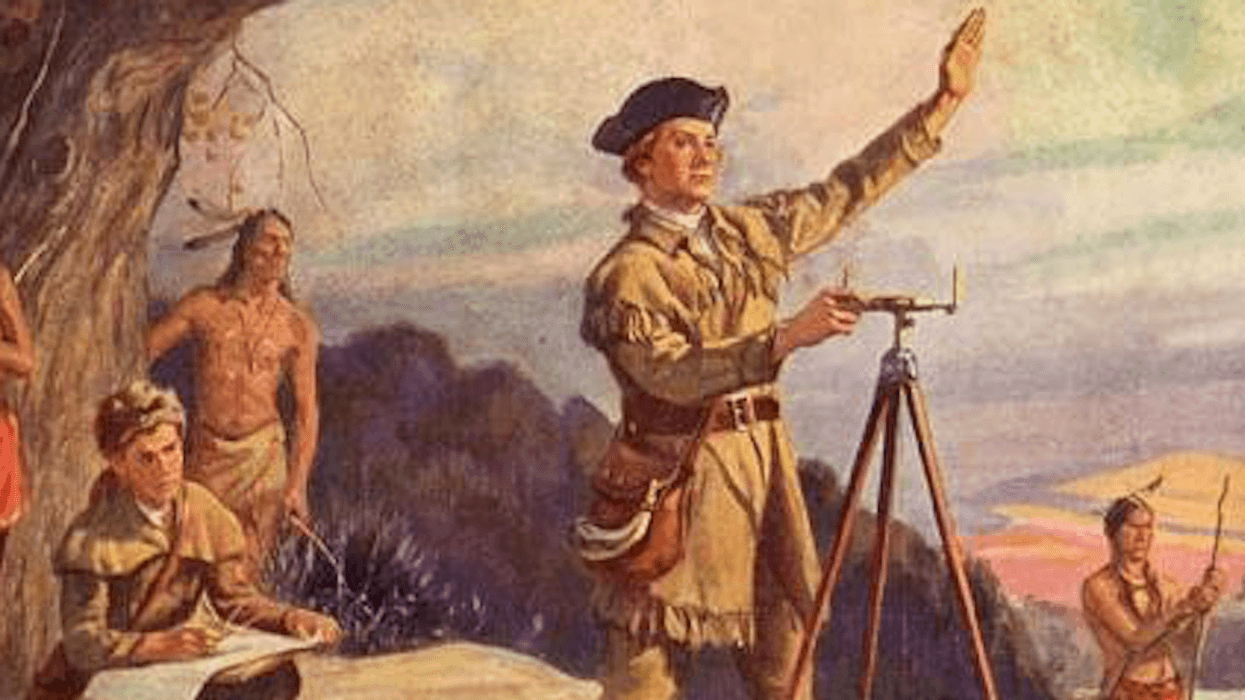

Europa Regina (1570). The ‘Military Mapping Maidens’ created tens of thousands of maps during World War II.

The ‘Military Mapping Maidens’ created tens of thousands of maps during World War II.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents. Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.

Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.

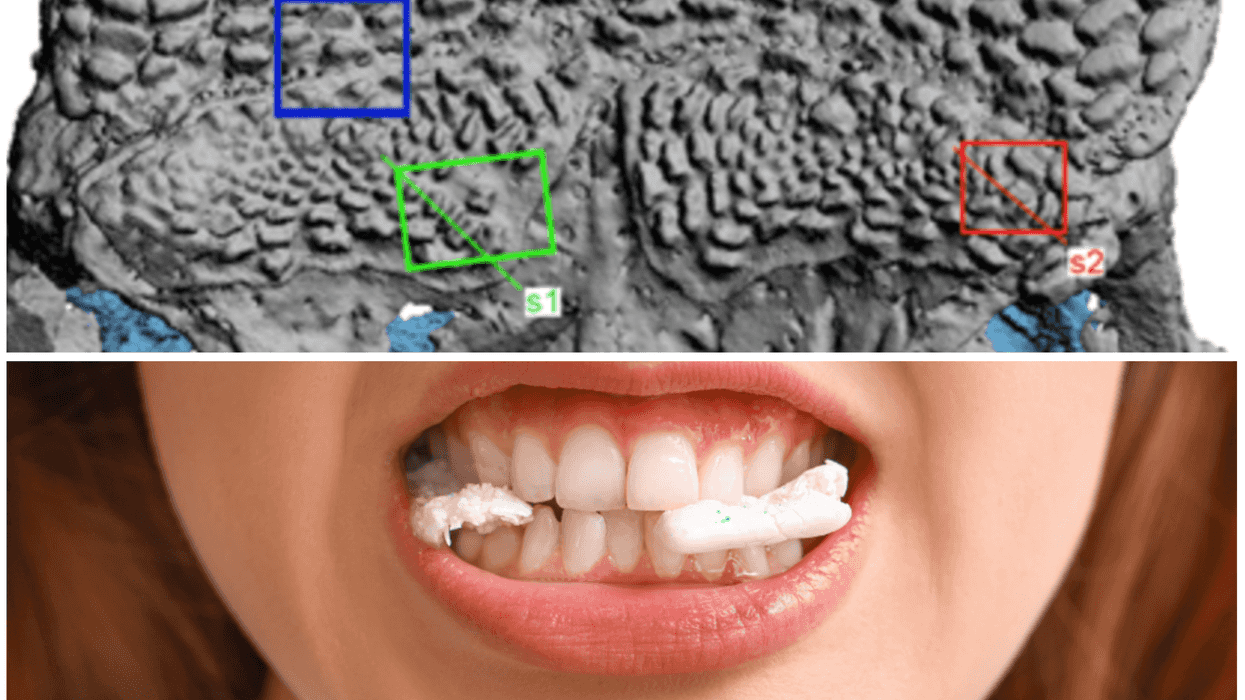

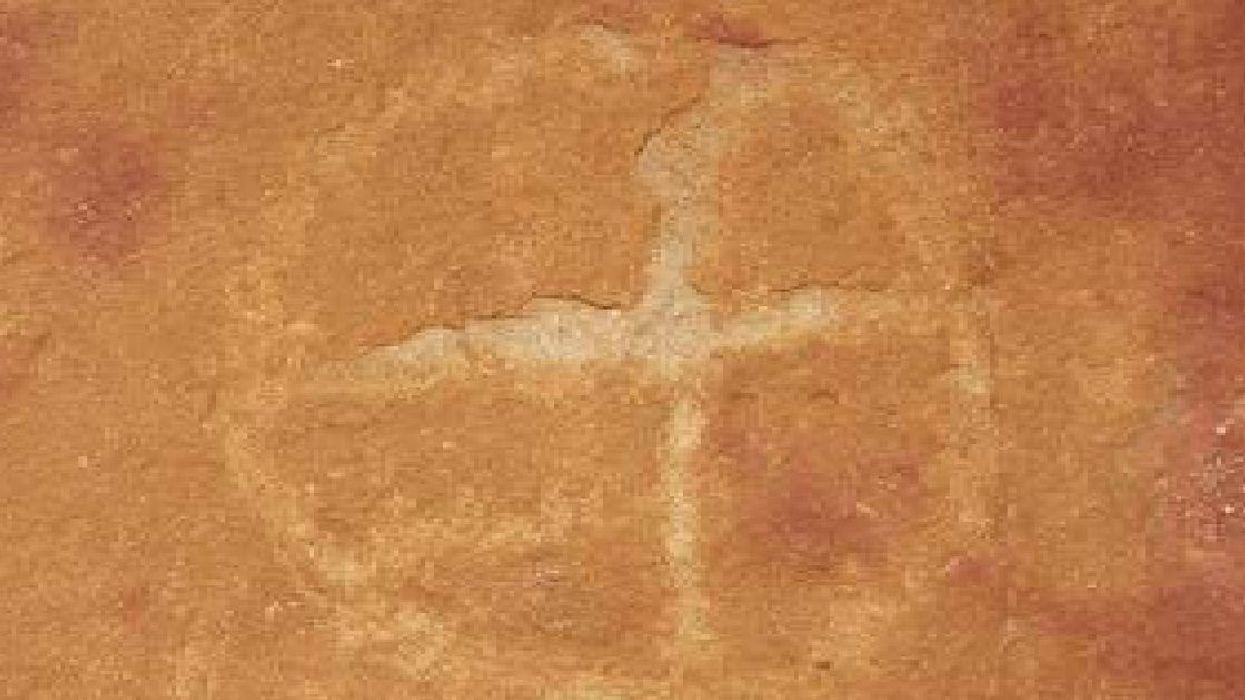

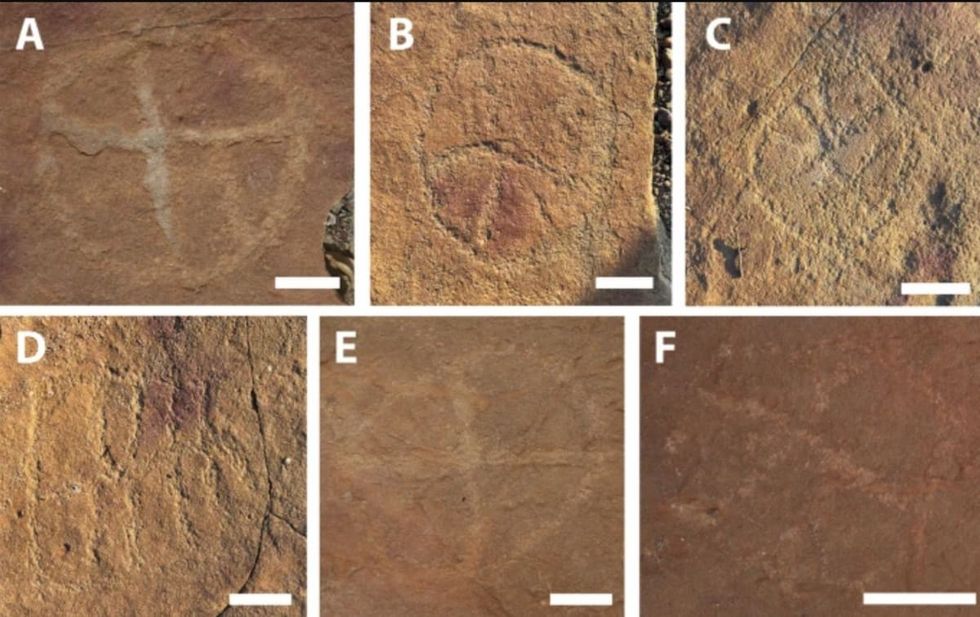

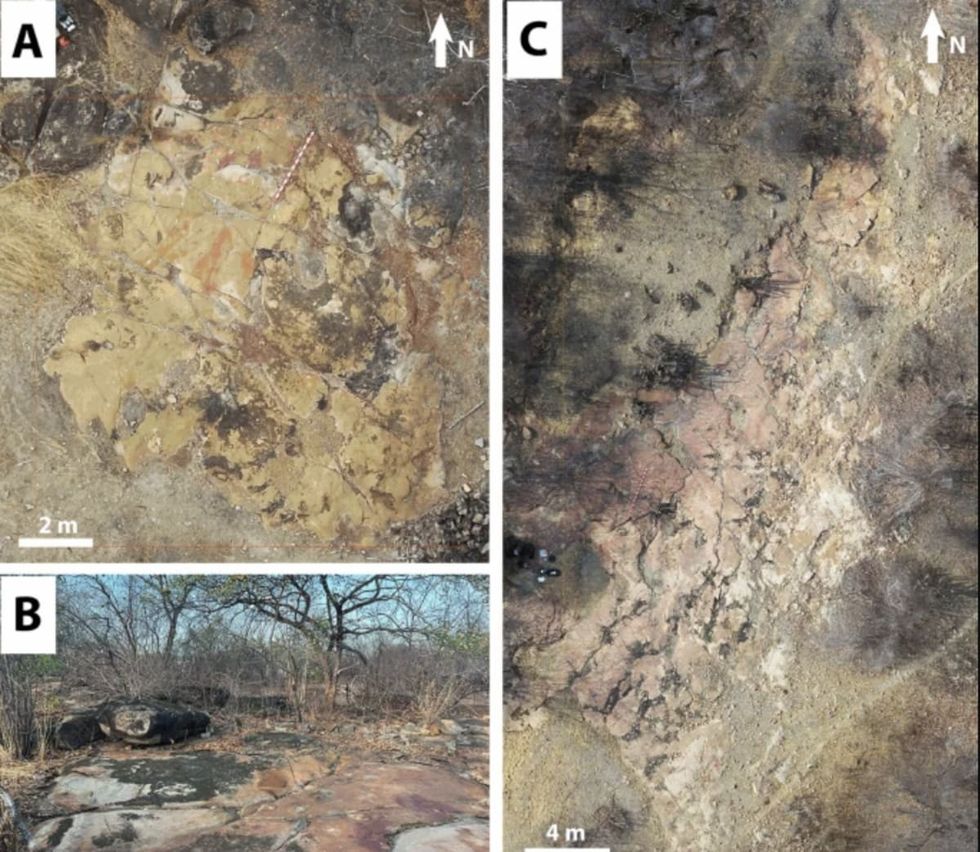

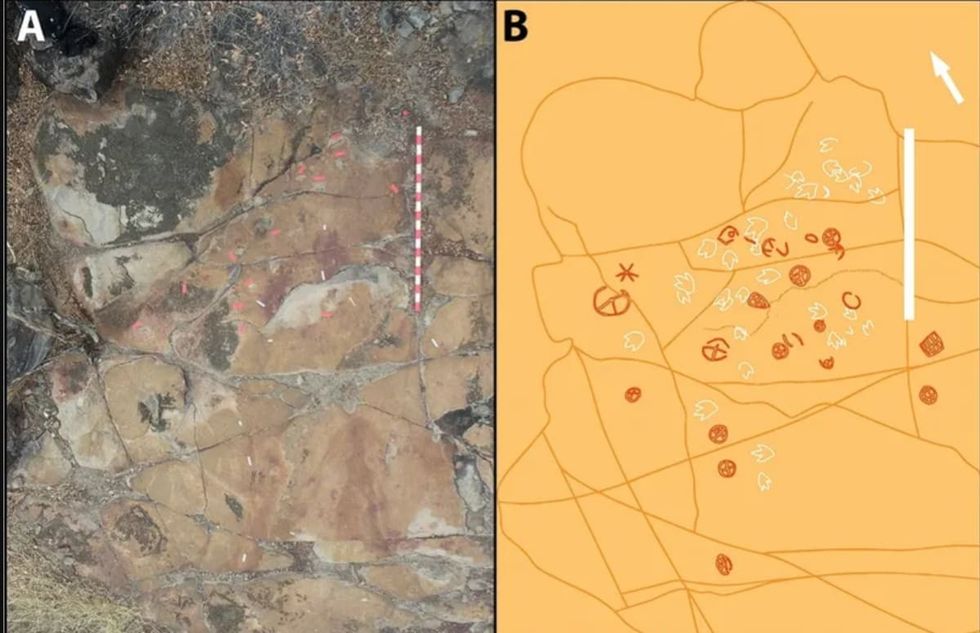

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

Sergei Krikalev in space.

Sergei Krikalev in space.