When we’re taught history, one of the first things we learn is about ancient maritime exploration. But we’re often missing something: we know that people traveled by boat, of course, but what we often don’t know is how. Scientists at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo, among other institutions in Japan and Taiwan, now have an answer to the latter.

In a project that took six years, these scientists learned exactly how ancient peoples traversed dangerous currents to travel from Taiwan to Japan by doing it themselves. It took 45 hours to complete the 140-mile journey in a dugout canoe crafted from a single Japanese cedar. In doing so, they revealed exciting facets of history that had once been unknown.

Traversing the Kuroshio current is no joke, and scientists learned a lot about the strength of ancient peoples. 7 Days of Science, www.youtube.com

In the course of their research, scientists learned “that around 30,000 years ago, humans made a sea crossing—without maps, metal tools or modern boats—from what is now called Taiwan to some of the islands in southern Japan, including Okinawa,” the University of Tokyo shared in a press release. The goal this team of 60 scientists had was to learn how they did it by initiating their own experimental archaeological test: which is to say, they’d do their best to create a scientifically and historically accurate duplication of how ancient peoples did it tens of thousands of years ago.

This included first figuring out the best kind of boat material to choose: early choices of reed and bamboo did not cut it and could not withstand the dangerous Kuroshio current, one of the strongest in the world. The next choice became a dugout canoe, which was made from a hollowed out tree with tools modeled after those that would have been used in the Stone Age. Still, this boat needed work: the initial model would flip over in the rushing water. Eventually, scientists were able to forge a version that worked after burning and polishing parts of the canoe and making several test trips.

Five members of the team set sail on their voyage in June 2019, and the results of their experiment have just recently been published. Like the travelers before them, they too used no maps or compasses and had only their knowledge of wind, sky, water, and instincts to guide them, the University of Tokyo shared. Their journey paddling, often for many hours without stopping, was a taxing one, and gave insight into what ancient peoples must have endured.

Scientists also learned there was no way ancient peoples came across any of this information by accident. Quite the opposite: it took a huge knowledge base and high levels of navigational skill to complete such a task, they wrote, not to mention incredible perseverance and strength. “Those male and female pioneers must have all been experienced paddlers with effective strategies and a strong will to explore the unknown,” project leader Professor Yousuke Kaifu said.

Their experimental archaeological expedition also revealed that it would have been difficult to go home once they arrived. “We do not think a return journey was possible. If you have a map and know the flow pattern of the Kuroshio, you can plan a return journey, but such things probably did not take place until much later in history,” Kaifu said. This means it’s possible that once these Paleolithic explorers left home, they may not have returned.

“Scientists try to reconstruct the processes of past human migrations, but it is often difficult to examine how challenging they really were,” Kaifu said. “One important message from the whole project was that our Paleolithic ancestors were real challengers. Like us today, they had to undertake strategic challenges to advance.”

Reuse over time and looting shifted and damaged the contents of an ancient Egyptian tomb. This displaced mummy mask could have a relationship to other artifacts already in museums around the world.Carlo Rindi Nuzzolo

Reuse over time and looting shifted and damaged the contents of an ancient Egyptian tomb. This displaced mummy mask could have a relationship to other artifacts already in museums around the world.Carlo Rindi Nuzzolo Archaeologists can use handheld 3D scanners to noninvasively map objects in very fine detail.Carlo Rindi Nuzzolo

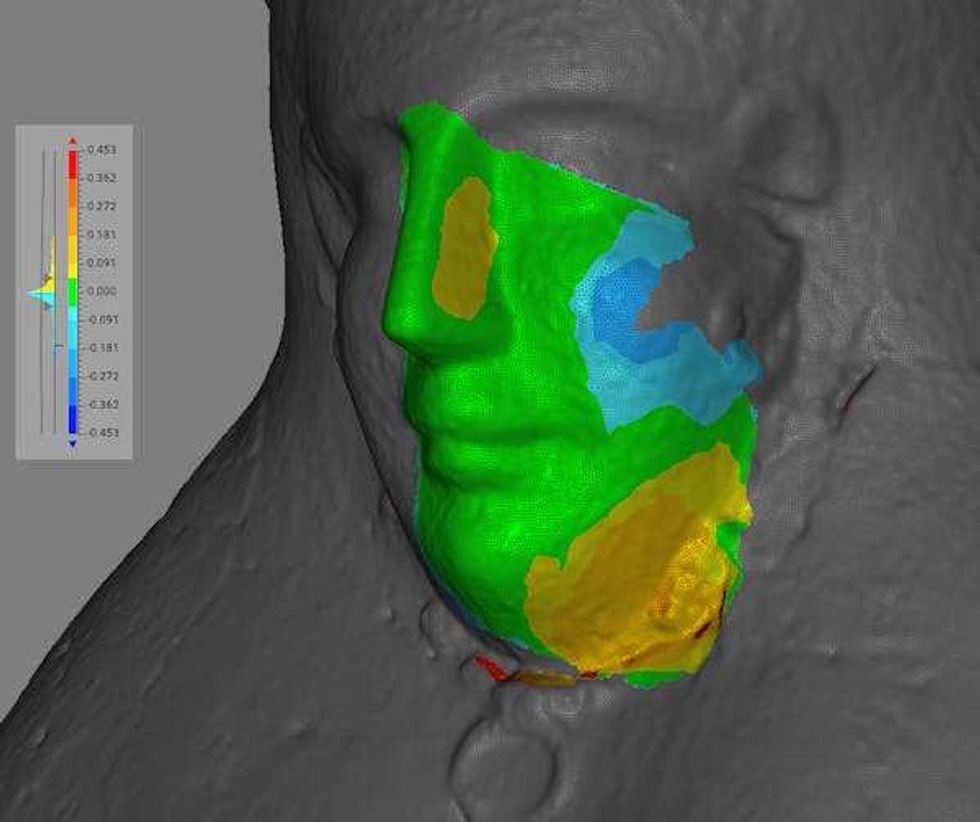

Archaeologists can use handheld 3D scanners to noninvasively map objects in very fine detail.Carlo Rindi Nuzzolo The mask reference surface is shown in gray, while the aligned fragment is colored based on the surface-to-surface distance at each point. Green indicates a good match with almost no distance. Cooler colors show areas where the fragment lies below the reference mask, and warmer colors show where it lies above.Carlo Rindi Nuzzolo

The mask reference surface is shown in gray, while the aligned fragment is colored based on the surface-to-surface distance at each point. Green indicates a good match with almost no distance. Cooler colors show areas where the fragment lies below the reference mask, and warmer colors show where it lies above.Carlo Rindi Nuzzolo The mask fragment was a very close match to a complete mask, suggesting they were made in the same mold.Carlo Rindi Nuzzolo

The mask fragment was a very close match to a complete mask, suggesting they were made in the same mold.Carlo Rindi Nuzzolo

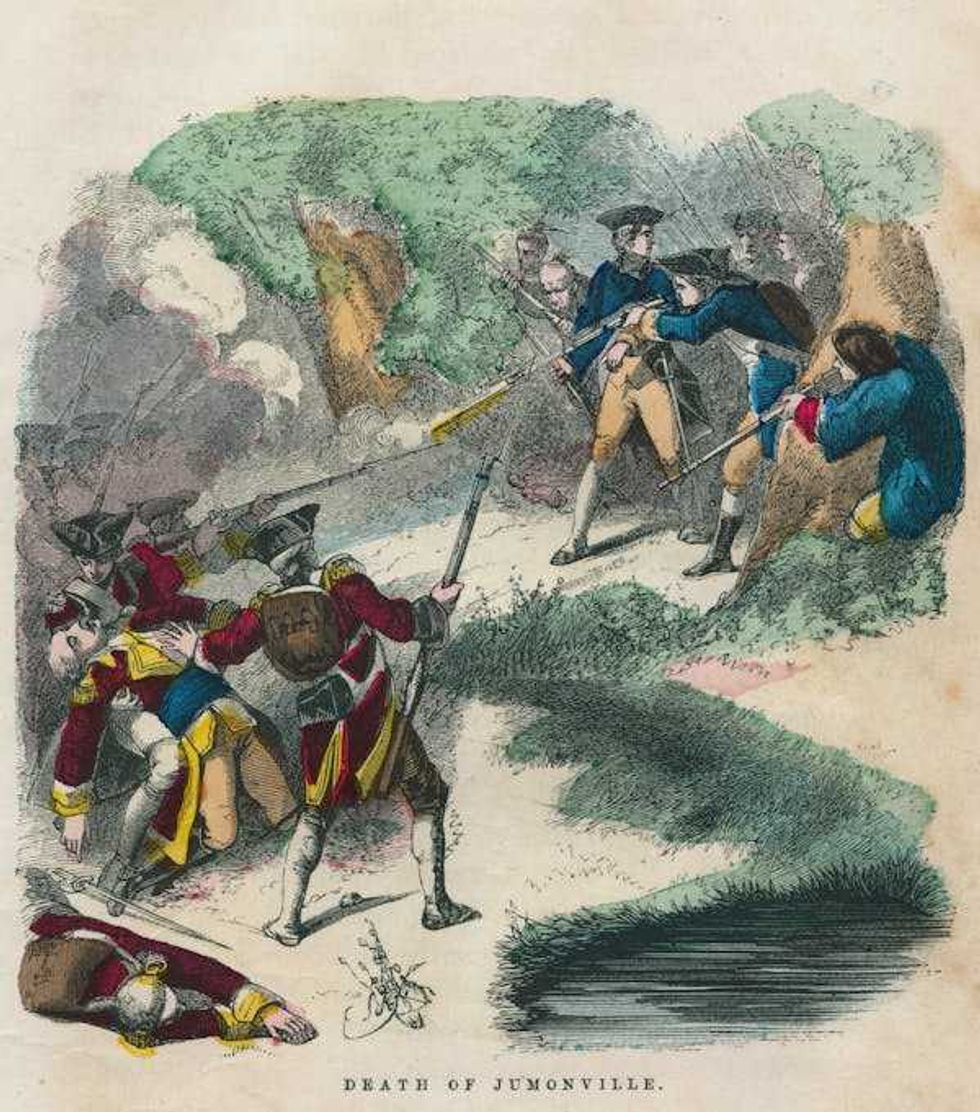

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War.

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War. Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity.

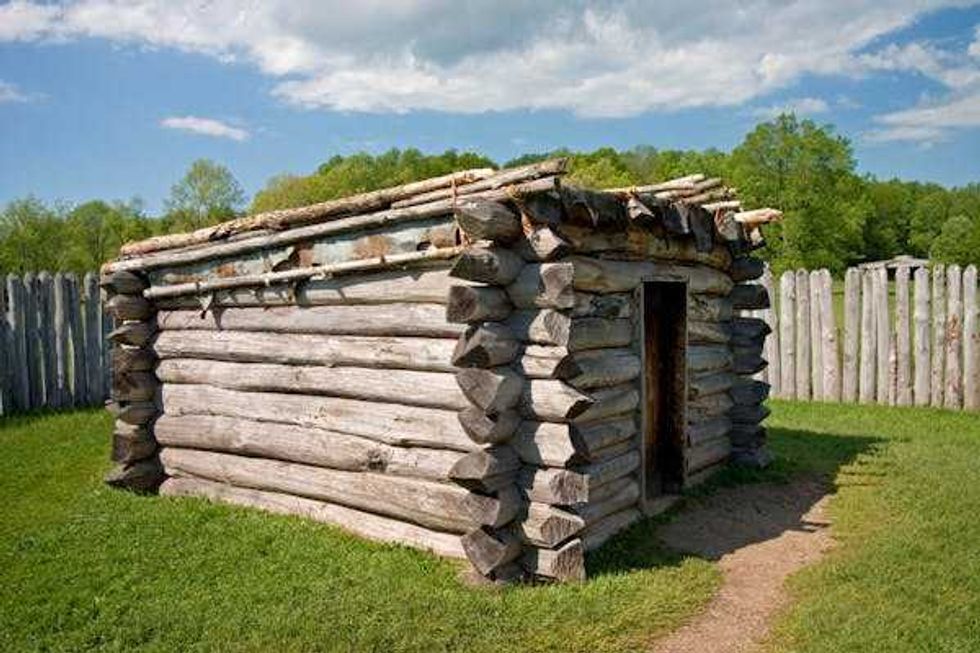

Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity. A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

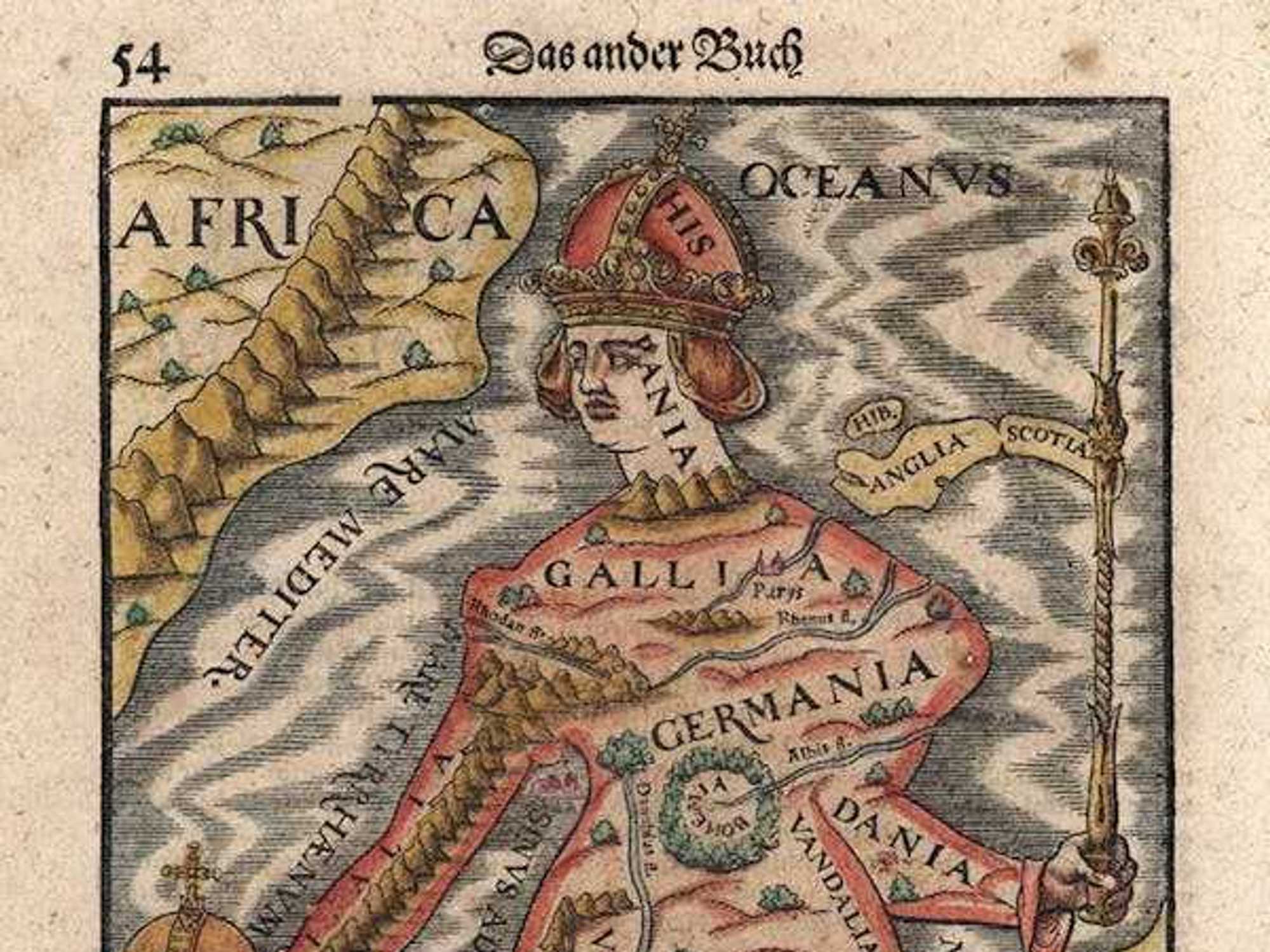

Europa Regina (1570).

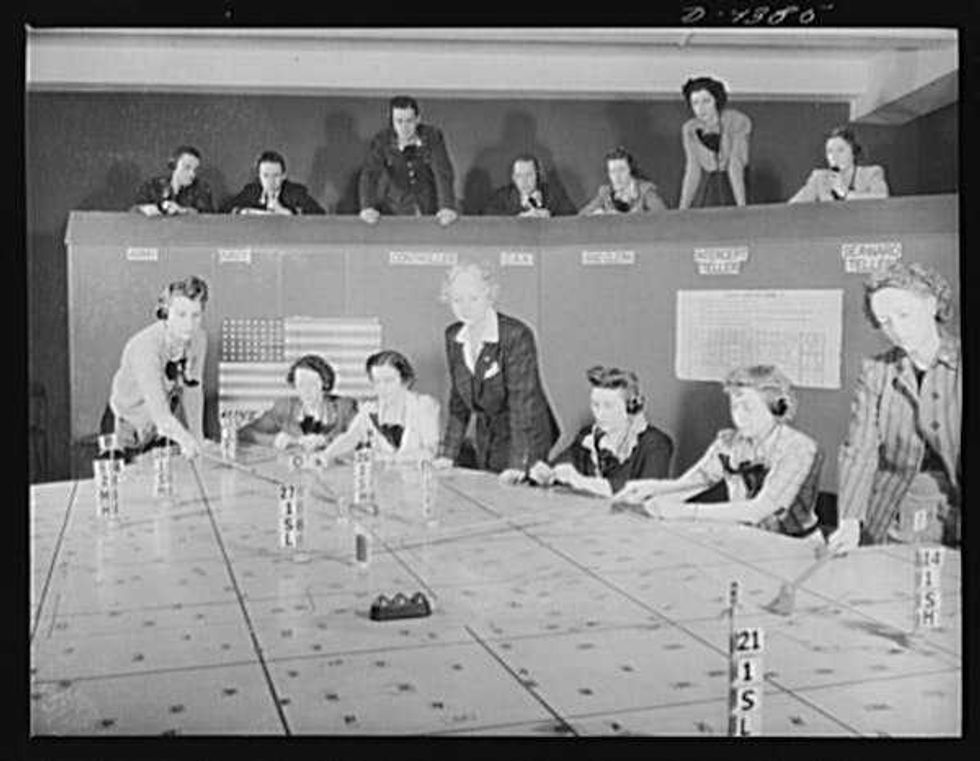

Europa Regina (1570). The ‘Military Mapping Maidens’ created tens of thousands of maps during World War II.

The ‘Military Mapping Maidens’ created tens of thousands of maps during World War II.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents. Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.

Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.

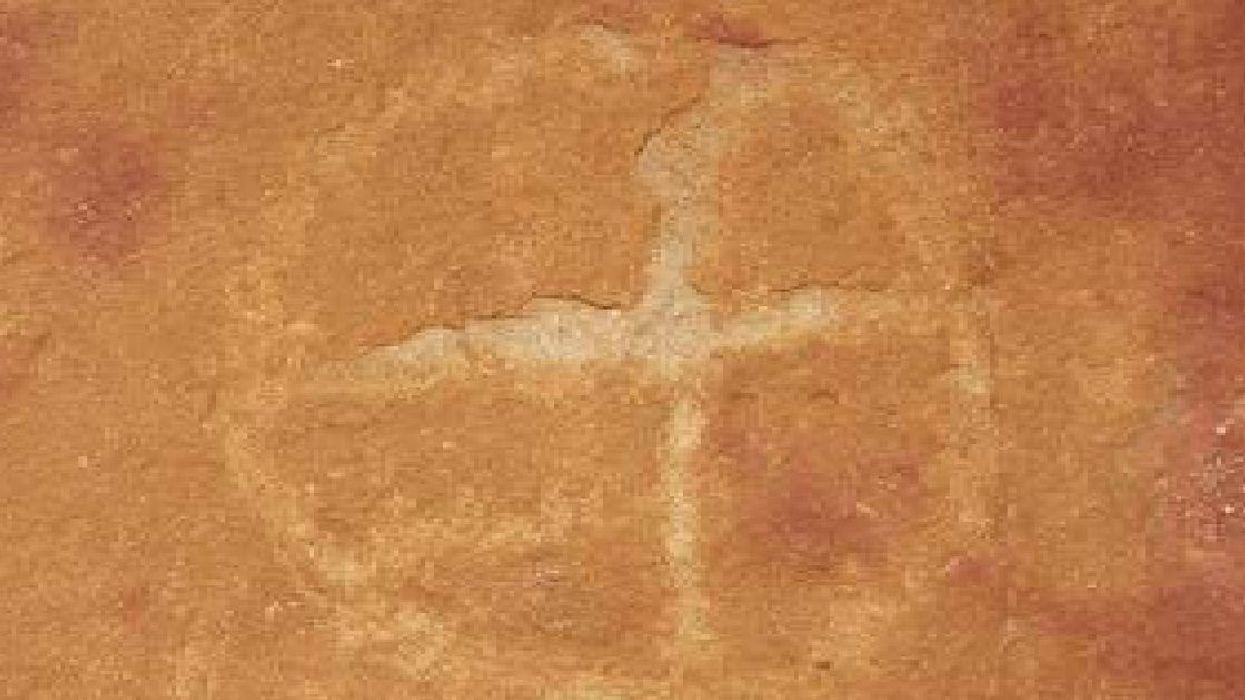

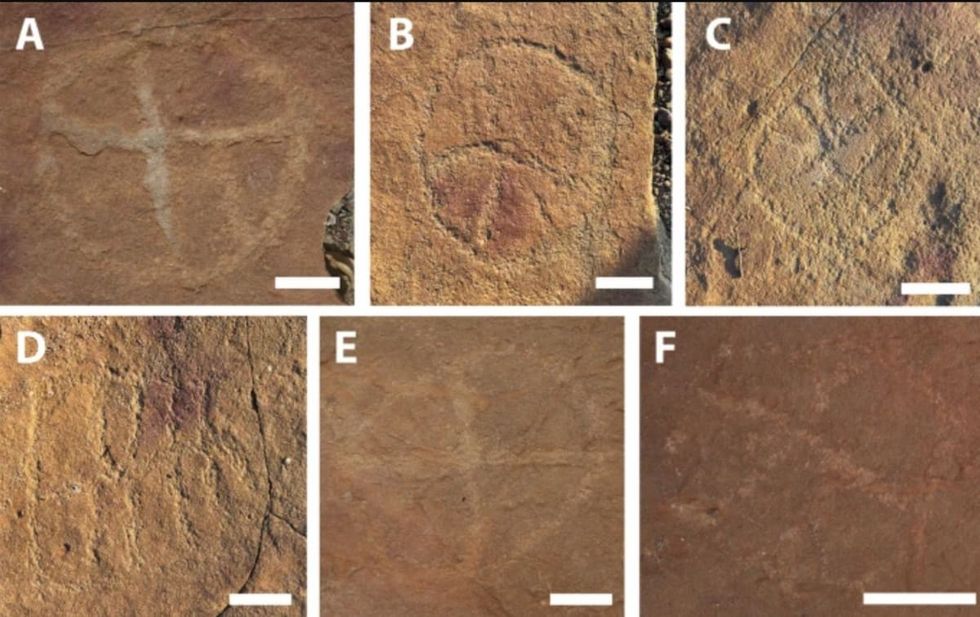

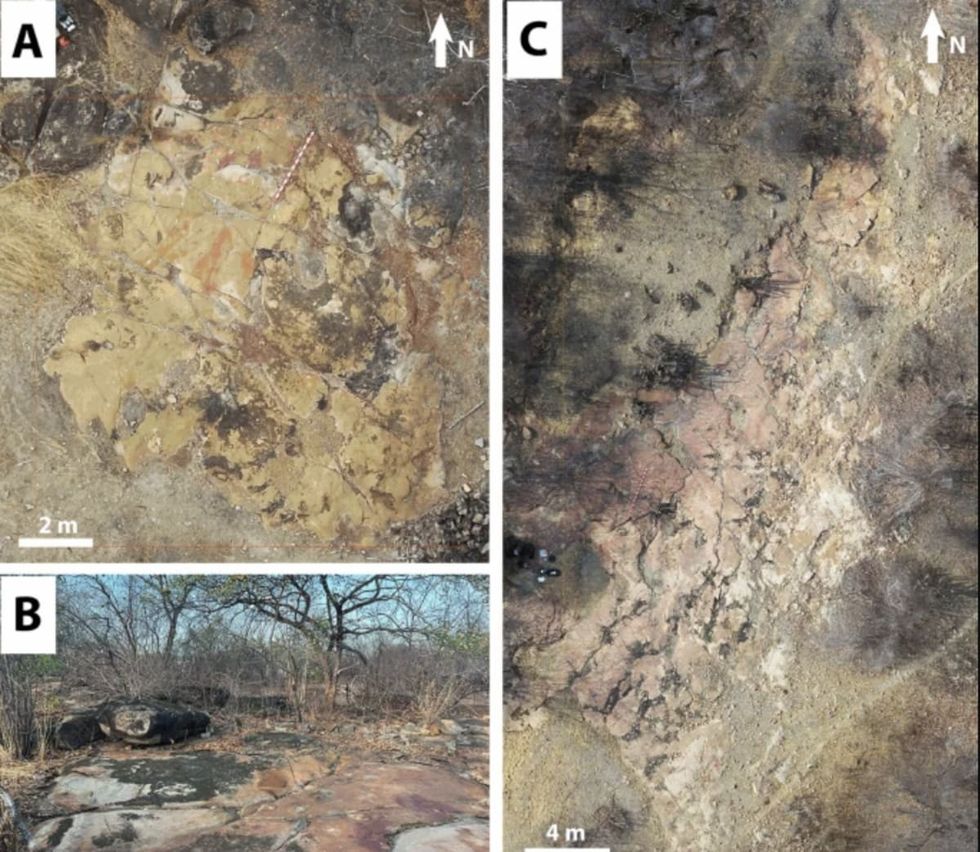

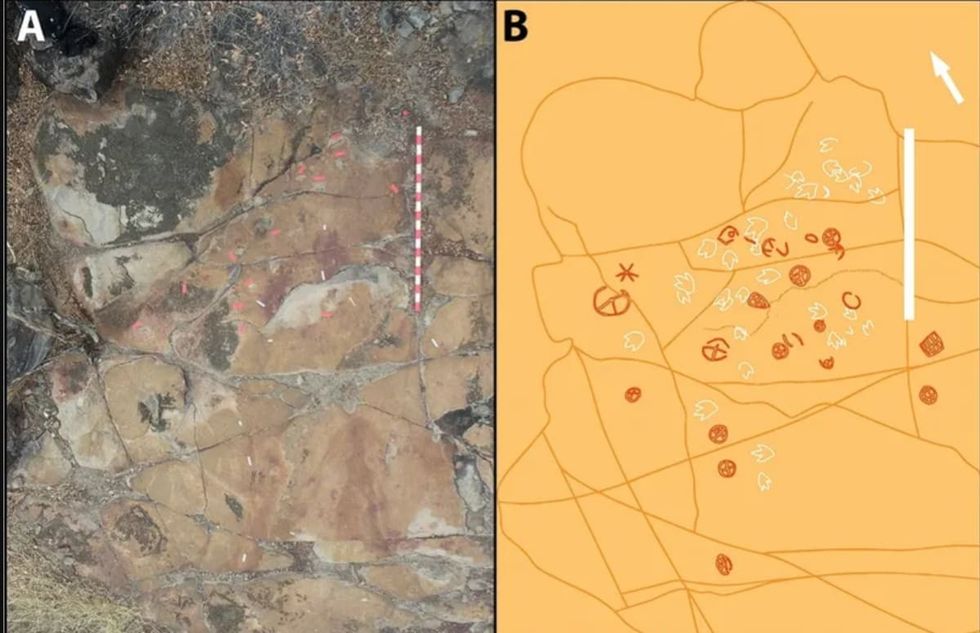

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

Sergei Krikalev in space.

Sergei Krikalev in space.