In case you missed it, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick sat down Friday night during a pregame performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” (Kaepernick did the same thing in his two previous games, but this time reporters noticed.) Asked why, the quarterback responded, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color.”

Amidst an uptick in political outspokenness by high-profile athletes, Kaepernick struck a uniquely sensitive nerve. Messing with the national anthem really angers Americans. (Sorry Gabby Douglas!) While the NFL, Players Association, and 49ers supported Kaepernick’s right to protest, bloggers, talking heads, Twitter goblins, and Tony Stewart attacked, claiming the quarterback had no respect for his country, and no reason to complain. The San Francisco police union demanded an apology.

We’ve been here before, debating an American athlete’s anthem etiquette in the context of making a political statement. A month before the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, Manhattanville College women’s basketball player Toni Smith began turning her back to the flag before games. “The government’s priorities are not bettering the quality of life for all of its people, but rather expanding its own power,” Smith said. “I can no longer, in good conscience, salute the flag.”

Smith, an obscure Division III athlete, became national news, enduring protests and heckling for the rest of the season. News media cast Smith as a traitor, implying her actions helped Saddam Hussein. Smith defended her behavior as patriotic, saying pride isn’t limited to performing an “empty slogan.”

Seven years earlier, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, a sweet-shooting Denver Nuggets guard with a quick release, made a similar decision. In the middle of the 1995-1996 season, Abdul-Rauf—who had converted to Islam several years earlier—told the Nuggets he wanted to avoid the national anthem, calling the tradition “nationalistic ritualism,” which the Koran forbids. After sitting down during the anthem later that season, Abdul-Rauf was suspended and forced by the NBA to compromise: He would stand for the song, but could bow his head and cup his hands in prayer.

Newspapers dubbed him a “disgrace.” Boos followed Abdul-Rauf on road trips, hate mail rained, the Nuggets traded him, and soon NBA teams stopped calling. “After the national anthem fiasco,” Abdul-Rauf said in 2010, “nobody really wanted to touch me.” In his first year out of the league, Abdul-Rauf’s Mississippi home was burned down (arson wasn’t ruled out) after being vandalized with Ku Klux Klan symbols.

This rabid defense of “The Star-Spangled Banner” often extends into the absurd. Mere musical re-interpretations have sparked outrage.

Before Game 5 of the 1968 World Series in Detroit, Puerto Rican singer Jose Feliciano performed a bluesy rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” on the acoustic guitar—pop-styled national anthems weren’t yet a thing. Thousands called the stadium to complain, and radio stations briefly stopped playing Feliciano’s records.

“I wanted to sing an anthem of praise to a country that had given my family and me a better life,” Feliciano wrote in 2011. “A great controversy was exploding across the country because I had chosen to alter my rendition of the national anthem to better portray my feelings of gratitude.”

In each case, claims to a patriotic identity, performed in non-traditional ways during “The Star-Spangled Banner,” offended fans. The argument typically goes that these inappropriate displays of dissatisfaction or difference insult America, like burning the banner itself. This argument typically disregards the possibility of expressing citizenship through accountability, or patriotism—in Feliciano’s case—through altered rendition.

Yet the song itself is an altered rendition. Francis Scott Key wrote the original poem, describing an American victory over British forces in Baltimore during the War of 1812, to the tune of an 18th century British drinking song.

Key, a slaveholding lawyer who prosecuted abolitionists, also originally wrote four verses—the third cheers how “blood has washed out” the “hireling and slave,” referring to black Americans who fought for the British in exchange for their freedom. America altered that part out.

The first high-profile instance of “The Star-Spangled Banner” at a sporting event came a century later, during Game 1 of the 1918 World Series. The day after the Chicago Federal Building was bombed, seventeen months into World War I, attendance was low. As a promotional stunt, the Chicago Cubs scheduled a military band to play Key’s song during the seventh-inning stretch. The performance drew the crowd to its feet. It still helps sell tickets today.

This is the tradition from which Kaepernick allegedly broke: a remix continuously molded by time, self-protection, conflict, and creative intervention into something more inclusive and American.

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

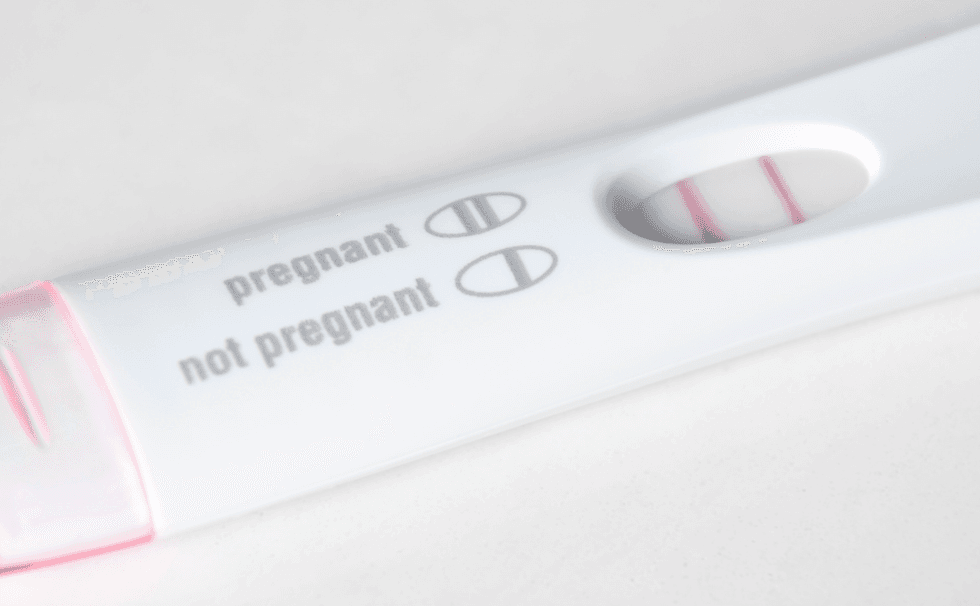

A home pregnancy test Canva

A home pregnancy test Canva

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

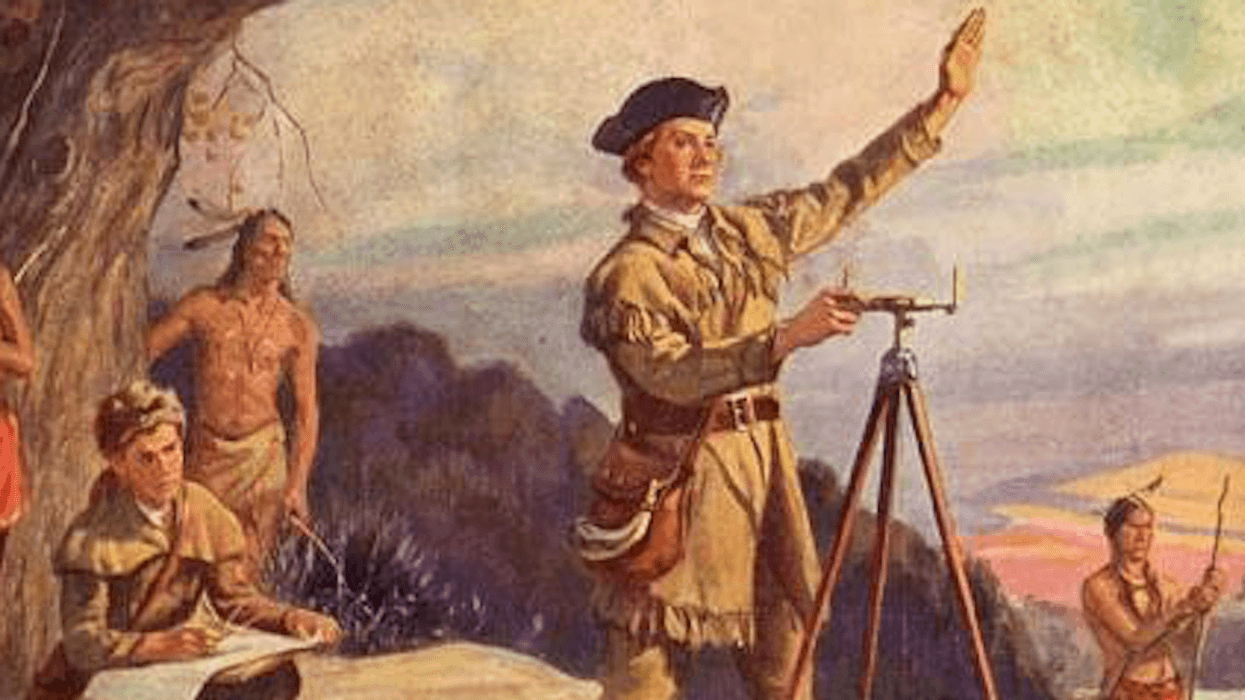

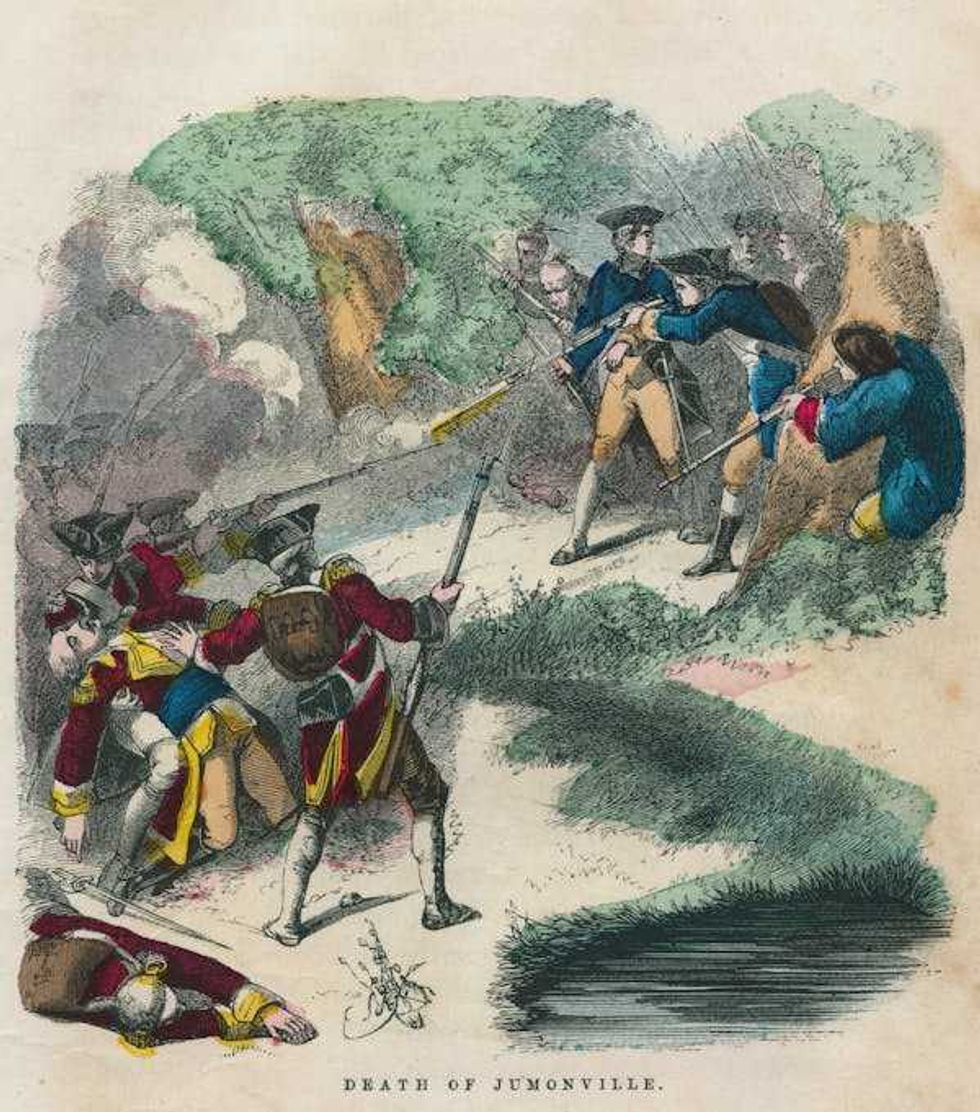

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War.

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War. Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity.

Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity. A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

A young woman scrolling on her phoneCanva

A young woman scrolling on her phoneCanva Gig of two cartoon penguins watching TV via

Gig of two cartoon penguins watching TV via  Gif of a storm trooper flipping through sings that say 'no' via

Gif of a storm trooper flipping through sings that say 'no' via