Parents are prepared for kids to bring home sports-related injuries, such as cuts, bruises, and scrapes—but not a concussion. Most parents don’t know the symptoms or the treatment guidelines for a brain injury. And unlike a bruise or a broken bone, children can’t see a concussion, leaving them just as confused about the injury and the severity.

That’s the number one reason kids give for playing through concussion symptoms: They didn’t know the risks and they weren’t aware of concussion symptoms, says Dr. Robert Cantu, a neurosurgery professor and codirector of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at the Boston University School of Medicine and senior advisor to the NFL Head, Neck, and Spine Committee. The second reason kids play through concussions is because they do not want to let the team down or lose a spot on the team.

Researchers are only beginning to understand the impact of concussions on youth. A 2015 study at the Boston University School of Medicine found an increase risk of CTE in the brains of kids who take repeated blows to the head before age 12. (Researchers used the brains of 40 former NFL players who played tackle football before the age of 12). Girls are roughly twice as likely to suffer a concussion as boys in similar sports, according to an 11-year-study of high schools published by the American Journal of Sports Medicine.

Ideally, parents, coaches, trainers, and kids should all to be aware of concussion symptoms and have a game plan for talking to their athletes about them. It’s not as easy as it sounds. To help parents talk to young athletes about brain injuries, Cantu authored the book, Concussions and Our Kids. GOOD spoke to Dr. Cantu and Dr. Jarrod Spencer, a sports psychologist for Mind of the Athlete, for advice on teaching kids about concussions, which they recommend for parents of kids involved in any sport where a collision is a possibility, from football to skateboarding to soccer.

When to talk

Sit down with your athlete early on in the preseason or first week of practice. As with any conversation about sports, wait until your child is showered, changed, fed, and rested, Spencer advises. Your child is much more likely to be receptive when she’s not famished and sweaty.

The main message is threefold, Cantu says, first and foremost, make it clear there’s an open door for your kid to talk to you about how they are feeling physically and emotionally. Second, stress the importance of valuing health, so that your child understands why it’s ok to seek professional help when something is hurting. Third, teach them the early signs and symptoms.

How to talk

Use age-appropriate language: “Being confused or foggy means a totally different thing to a high school athlete than a kid at age 5,” Cantu notes. For a 5-year-old, use words such as “different”—as in “Is there anything different with your balance or your thinking?” You can also ask about headaches, dizziness, trouble with eyesight or sensitivity or differences with light and noise. For a high schooler, you can go into more detail about how cognitive processes might slow down after a concussion. Make sure they are aware that short-term memory is commonly impaired with concussions, so they can take note of whether their homework is taking longer than usual or whether certain tasks, such as memorizing vocab lists, seem more difficult following a head injury.

Parents should vary the frequency, duration, and intensity of these conversations depending on the age of the child, Spencer says. While it may seem that concussion messaging is omnipresent these days, the ultimate responsibility for concussion education rests with parents, he says. “A conversation about concussion is a conversation about taking care of your overall health and well-being while playing sports,” he says. And, especially in youth sports, where concussion policies vary widely.

Plan recovery

It’s not necessary to go into detail on the mechanisms of how concussions impact the brain. Instead, emphasize that if recognized and treated, symptoms usually clear up and the athlete can go back to his sport. Remind your athlete that severe consequences can occur when people try to play through symptoms. If your athlete wants more details, you can share the two main risks of playing through a head injury. Although rare, second impact syndrome, or additional brain trauma before the brain is properly healed, can be fatal, Cantu says. The more common risk is that an additional hit before recovery can exponentially lengthen the time it takes to overcome symptoms.

Keep the mental health of your athlete front and center, Spencer advises. While almost everyone in our society is aware of concussions today, very few are aware of the mental health challenges that accompany concussions. “If you shut down a high school athlete who’s used to working out intensely every single day, they probably won’t feel so good,” he says. Removing the daily boost of endorphins and serotonin, along with time spent with teammates, can provoke anxiety or depression, he says.

Think prevention

Make sure that kids in concussion-prone sports aren’t taking on unnecessary brain impact. While safer practices are being instituted at the highest levels of sport, not all youth organizations have caught on. NFL players are now allowed to hit at only 14 practices during the season, and not at all in the offseason, Cantu points out. If your kid wants to play football before age 14, he recommends flag football. For soccer players, make sure they’re not heading the ball under age 14. Ice hockey players should not be involved in full-body checking before age 14. While most youth leagues are heading in that direction, it’s ultimately up to parents to find out how policies are implemented. “I think what you’re going to hear is that everyone is saying all the right things, but the reality in how they’re actually carried out may vary,” Spencer says.

Don’t worry about being a helicopter parent if your kid sustains a blow to the head: You know your kid better than even the best coach, and sometimes a parent can intuit whether a kid is “off” with just a word or a glance. Don’t hesitate to pull him/her from the game “We the adult have to protect the athlete from themselves,” Spencer says. “Because left unto themselves they will not take themselves out. It’s the coaches’ and parents’ responsibility. ”

Be prepared

Get a baseline test at your clinic or do it at home: After talking to Cantu, I spent 30 minutes running my kids through various balance exercises, memory tests, and symptom checklists at home. (On Cantu’s recommendation, we used the BESS test for balance, the King-Devick test for vision tracking, and the SCAT for symptoms. The kids loved it, and I feel a bit better knowing that the next time one of them ends up on the ground, I’ll know what to do.

Finally, don’t obsess. The most important thing to understand, Cantu says, is that no brain trauma is good, but if we react well, it will probably turn out ok. “If you can avoid it, avoid it, but if you can’t, so be it,” he says.

A woman relaxes with a book at homeCanva

A woman relaxes with a book at homeCanva An eviction notice is being attached to a doorCanva

An eviction notice is being attached to a doorCanva Gif of Kristen Bell saying 'Ya basic!' via

Gif of Kristen Bell saying 'Ya basic!' via

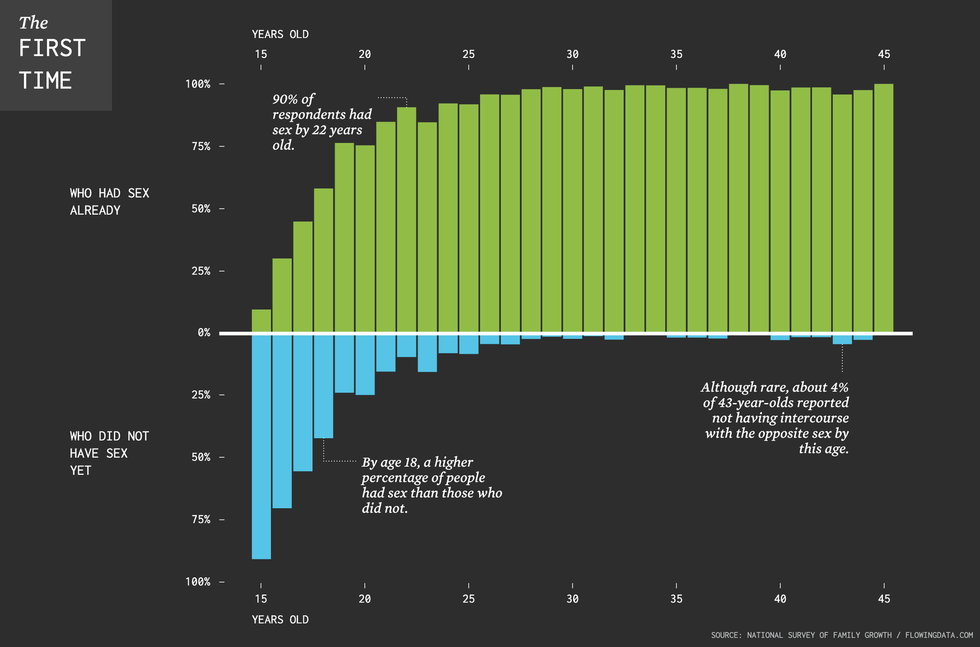

The chart illustrates that between ages 16 and 20, roughly half the population loses their virginity. By age 22, 90% of the population has had sex.

The chart illustrates that between ages 16 and 20, roughly half the population loses their virginity. By age 22, 90% of the population has had sex. A group of young people hold their phonesCanva

A group of young people hold their phonesCanva

(LEFT) Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale and (RIGHT) Ray Bolger as Scarecrow from "The Wizard of OZ"CBS/

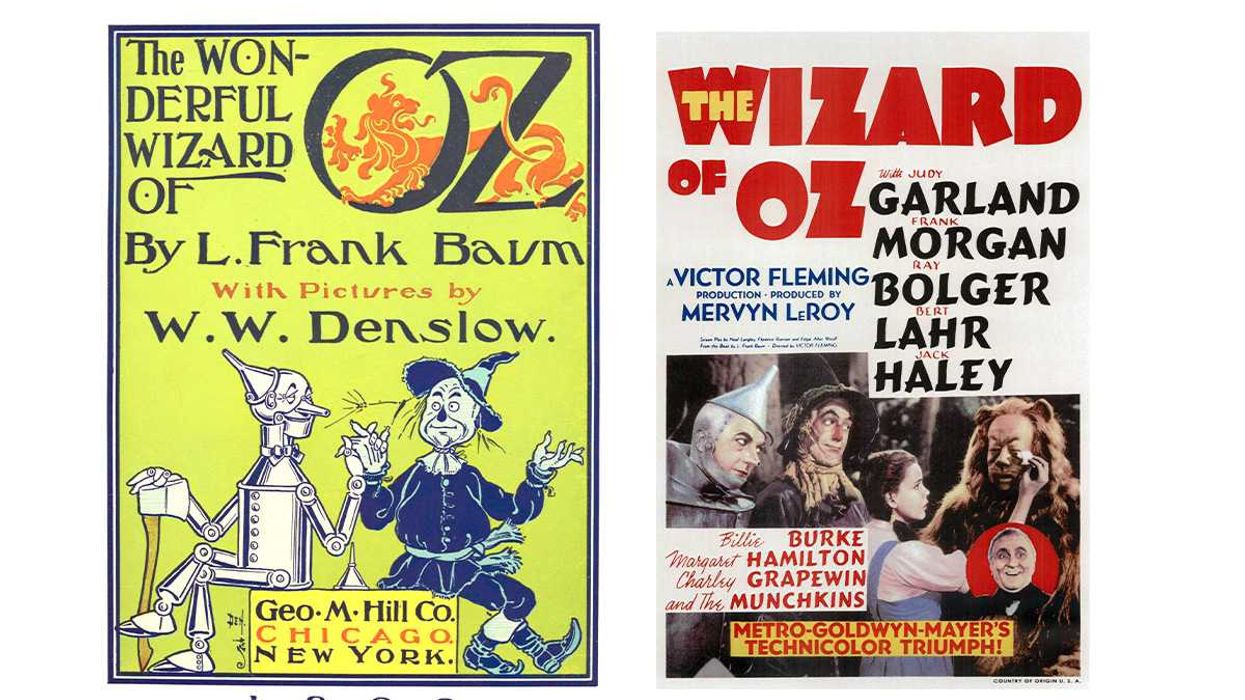

(LEFT) Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale and (RIGHT) Ray Bolger as Scarecrow from "The Wizard of OZ"CBS/  (LEFT) The Wonderful Wizard of Oz children's novel and (RIGHT) The Wizard of Oz movie poster.William Wallace Denslow/

(LEFT) The Wonderful Wizard of Oz children's novel and (RIGHT) The Wizard of Oz movie poster.William Wallace Denslow/

A frustrated woman at a car dealershipCanva

A frustrated woman at a car dealershipCanva Bee Arthur gif asking "What do you want from me?" via

Bee Arthur gif asking "What do you want from me?" via

A couple on a lunch dateCanva

A couple on a lunch dateCanva Gif of Obama saying "Man, that's shady" via

Gif of Obama saying "Man, that's shady" via

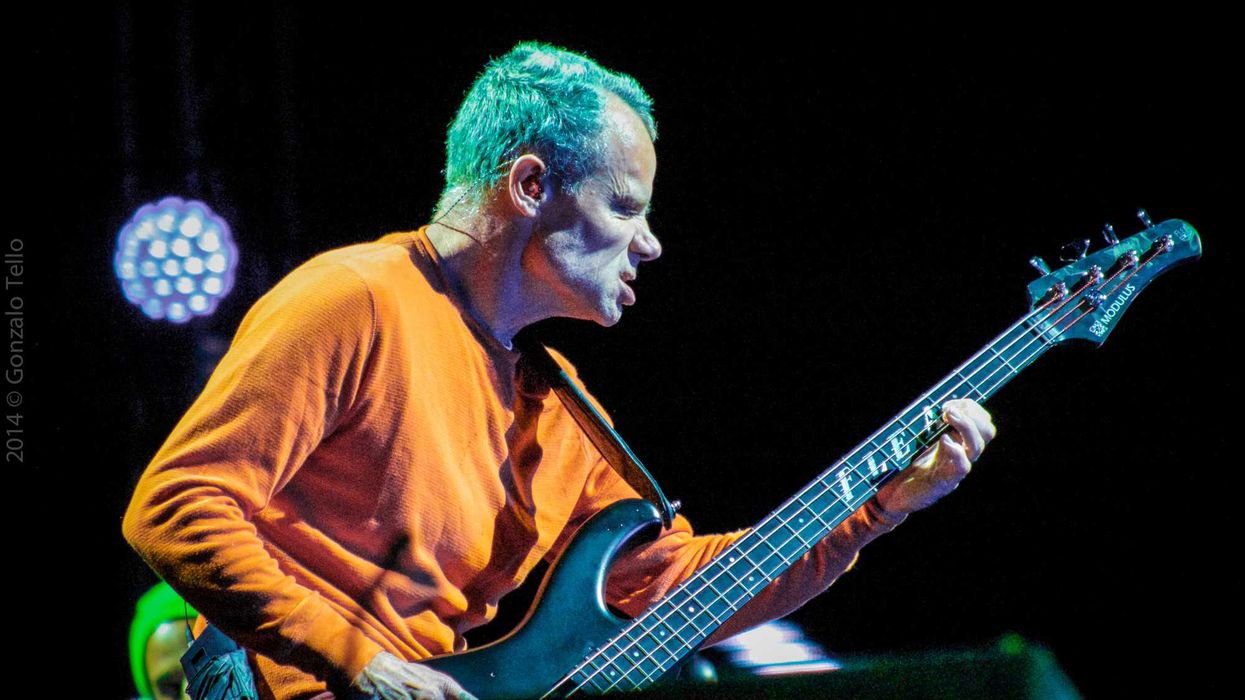

Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea at Lollapalooza Chile in 2014.Cancha General/

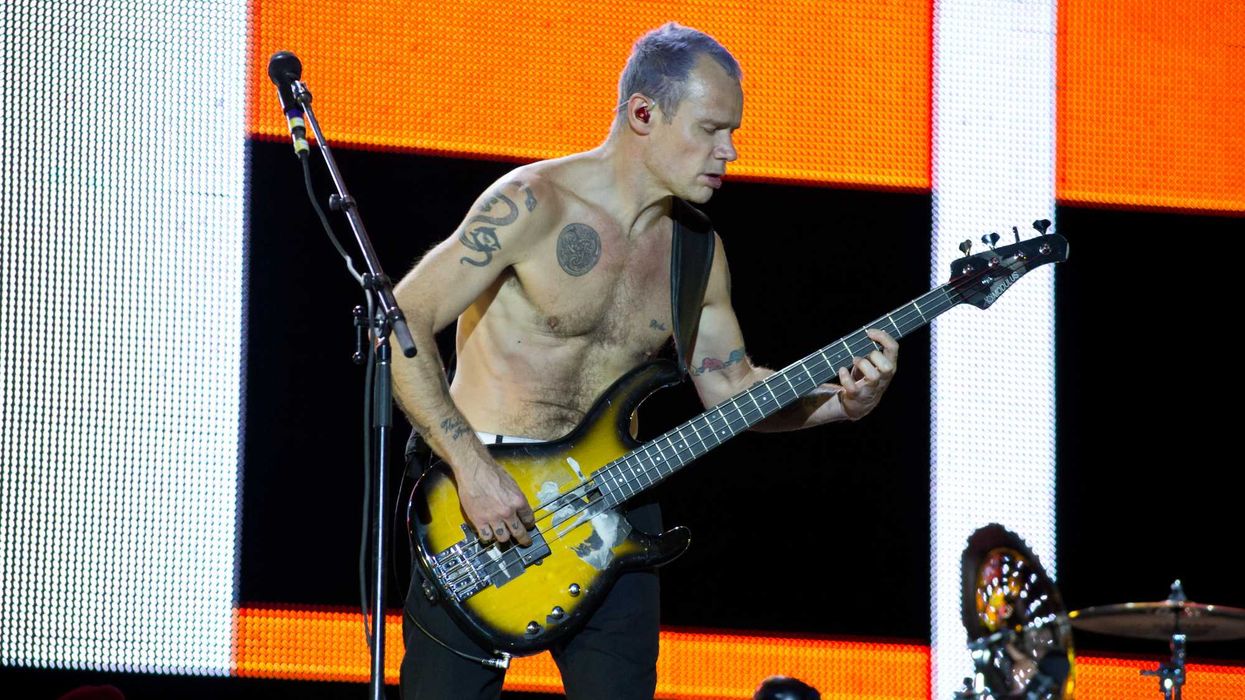

Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea at Lollapalooza Chile in 2014.Cancha General/  Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea at Rock in Rio Madrid in 2012.Carlos Delgado/

Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea at Rock in Rio Madrid in 2012.Carlos Delgado/