Former punter Chris Kluwe is participating in a medical marijuana study. (Photo by KDoebler via Wikimedia Commons)

It’s been a landmark year for medical marijuana in football. This season we saw the first active players publicly advocate for cannabis, backed by a choir of retirees; American universities undertake unprecedented studies into marijuana’s medical effects on current and former players; and even the NFL Players Association launch a committee to investigate pot for pain management.

Meanwhile, the NFL itself refuses to acknowledge any legitimate medical interest in the plant. None of the $100 million that the NFL recently pledged for player health research will go toward studying cannabinoids, the chemical compounds in cannabis. The league enforces its uniquely strict prohibition with an iron fist; it recently suspended Buffalo Bills offensive tackle Seantrel Henderson, who has Crohn’s disease—one of New York state’s qualifying conditions for medical marijuana—for 10 games. After election day, 23 of the NFL’s 32 teams now play in states that have approved medical marijuana.

The league’s climate of resistance also works to obstruct science. Late this summer the University of Pennsylvania and Johns Hopkins University invited active players to participate in an anonymous study designed to track health, injuries, and opioid and cannabinoid use during this season. Despite meeting with the study’s lead researcher, the NFLPA sent players a letter warning that their identity might not be protected from the league if they participated, leading the few players who already signed up to drop out.

Constance Finley of Constance Therapeutics. (Image via Twitter)

But the industry is pushing forward. Constance Finley, a 63-year-old psychologist turned investment advisor turned pharmacologist, runs Constance Therapeutics in Richmond, California. The company, which Finley founded in 2008, was one of the country’s first to professionally manufacture cannabis oils for medicinal use.

This spring Constance Therapeutics formed a partnership with the Gridiron Cannabis Coalition, a consortium of retired NFL players dedicated to tackling the league’s concussion and opioid crisis by supporting and advancing medical marijuana research. Monroe, two-time Pro Bowl lineman Kyle Turley, legendary Dolphins running back Ricky Williams, ex-Minnesota Vikings punter Chris Kluwe, and former New Orleans Saints tight end Boo Williams count themselves as members.

Constance Therapeutics and the Coalition announced their first move in July: an eight-week pilot study quantifying the effects of Constance’s oils on retired players’ pain symptoms. Finley tells GOOD that GCC is still recruiting participants, but that “about 30 players” have agreed to join. The Pennsylvania and Johns Hopkins researchers are also recruiting participants for a study of retired NFL players’ health and substance use, which they announced alongside the active player study. Scientific research about marijuana’s influence on football’s debilitating health effects is coming.

The underdogs leading the way

Finley has one of those medical marijuana stories that sounds like a myth—or maybe a miracle. A severe autoimmune disorder left her housebound for 10 years, starting in the mid-1990s, and she says her prescribed medications “almost killed” her. While researching alternative care online she discovered Canadian Rick Simpson’s homemade topical cannabis oil, Phoenix Tears, which he claimed cured his skin cancer. A self-declared cannabis skeptic, Finley started making her own oil—“I was out of options,” she says—and found it relieved her chronic pain.

“I got so much better that my doctor started asking me about it,” Finley says. “I thought they would look askew at me. I finally did tell them. They said, ‘Oh my god, everyone here needs that.’”

Finley’s doctor started referring to her patients with Stage IV cancer—the “hopeless,” she says—for treatment with the oil, supplementing their existing treatments like chemotherapy. When SF Weekly published a cover story on Finley’s work in 2013, she claimed that 25 of her 26 patients over the past year survived. “I realized we had to take this very, very seriously,” she says.

Finley began attending conferences held by European cannabinoid research societies and networking with and taking classes from phytochemists and pharmacologists, while searching stateside for partners and investment to fund her own research. Last November, she reached out to the Gridiron Cannabis Coalition, which had launched five months earlier.

“Constance is one of a handful of companies, and people, who we consider on the forefront of whole-plant medicine,” Matthew Bucciero, a San Diego-based cannabis venture capitalist and GCC’s co-founder, tells GOOD. “Their interest (supported) our ability, we felt, to achieve the first stage of our long-term goals, which is getting real information under us.”

In April, Constance Therapeutics and GCC announced a partnership dedicated to advancing “research into the benefits that whole plant cannabis extracts can offer athletes suffering from chronic pain, brain trauma, and other sports-related injuries.” In July they unveiled plans for a pilot study coordinated by Dr. Arno Hazekamp, head of research and development for medical cultivator Bedrocan BV, which supplies the Dutch Health Ministry’s marijuana program, to document pain symptoms in retired players and the effects of different cannabis oils.

“The current pilot study setup is designed to learn as much as we can under the current California medicinal cannabis regulations,” Hazekamp, whom Finley befriended at an International Cannabinoid Research Society symposium, tells GOOD. “It is our hope that this will change the landscape for cannabis research in the U.S. and pave the way for future clinical studies.”

At the beginning of an eight-week time period, an independent medical professional will assess players’ full medical histories, including past and present substance use. Over the course of the study, players will take recommended doses of cannabis oil and track their health using self-reporting scales like the McGill Pain Questionnaire and the Beck Depression Inventory. At the end of the eight-week protocol, a third party will repeat the original medical assessment procedure.

The study’s results will be the first data showing how cannabis influences pain in retired NFL players.

The long game

Bucciero and Mike Cindrich, an attorney and GCC co-founder, both played college football—the former at Lehigh, the latter at Bucknell. Cindrich, son of renowned sports agent Ralph Cindrich, grew up in NFL locker rooms. After discussions with noted pro-pot retiree and fellow San Diegan Kyle Turley, whose attorney Cindrich met surfing in Costa Rica, they launched the coalition to explore cannabis’ ability to confront two problems: traumatic brain injury and opioid dependency.

“We really don’t have a viable pipeline to getting this information. We felt it was our responsibility to work with these guys,” Bucciero says. “Whether it ends up being cannabis is the answer, or part of the answer, or very little, I don’t know the answer to that question. But right now, it’s about options.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]The study’s results will be the first data showing how cannabis influences pain in retired NFL players.[/quote]

Toward that end, Bucciero and Cindrich are expanding their operation. In September they launched the Gridiron Cannabis Foundation, a 501(c)(3) specifically designed to support research, education, and treatment—including coordinating efforts like the Constance Therapeutics study. Bucciero says that GCF is working on future research and is also developing a cannabinoid-oriented pain treatment facility specifically for athletes, which he hopes will be operational in the next two years.

The NFL’s resistance to cannabis won’t stop these efforts—nor the development of synthetic cannabinoid medicines by pharmaceutical upstarts like Kannalife and GW Pharmaceuticals—which could serve as a blueprint for whenever the league does embrace the plant. Still the question remains, why the resistance?

“We should be asking ourselves, why are we so unwilling to perform basic scientific due diligence on this one specific compound or series of compounds?” Kluwe tells GOOD. “This can help players, but this can also help other people. If it is a better alternative, well, we should know that. That means being able to do research on it.”

Maya Angelou reciting her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993.William J. Clinton Presidential Library/

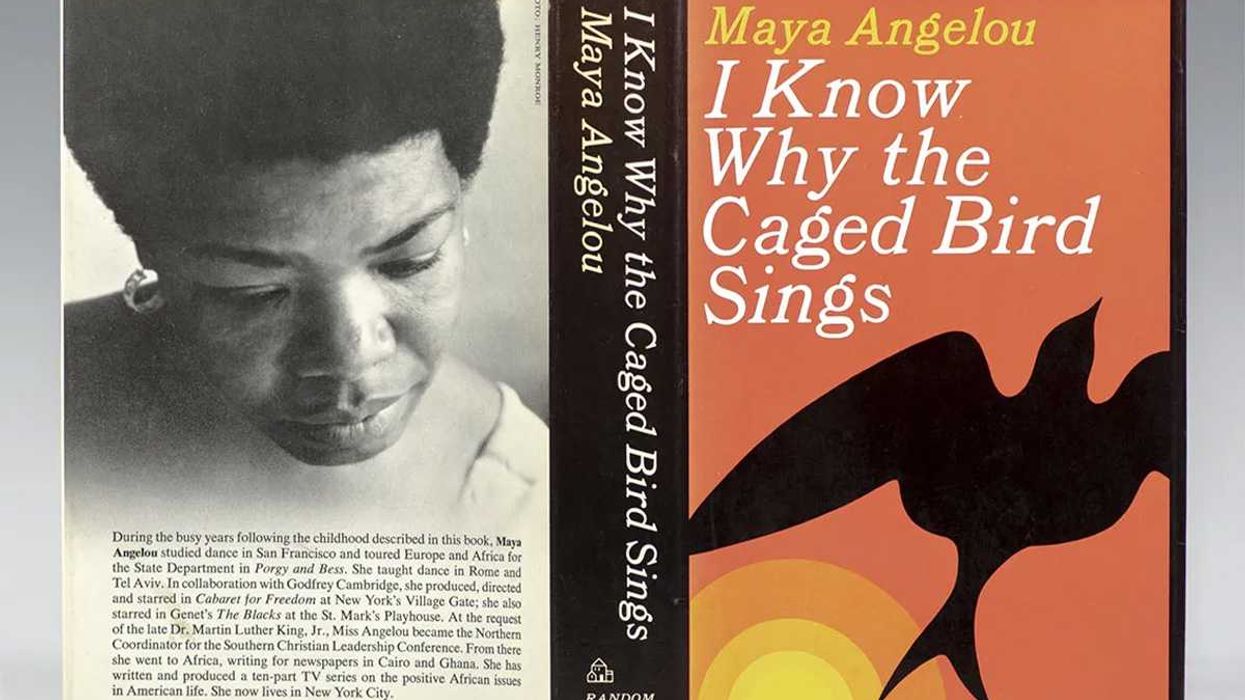

Maya Angelou reciting her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993.William J. Clinton Presidential Library/  First edition front and back covers and spine of "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings."Raptis Rare Books/

First edition front and back covers and spine of "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings."Raptis Rare Books/

Tow truck towing a car in its bedCanva

Tow truck towing a car in its bedCanva  Sad woman looks at her phoneCanva

Sad woman looks at her phoneCanva  A group of young people at a house partyCanva

A group of young people at a house partyCanva  Fed-up woman gif

Fed-up woman gif Police show up at a house party

Police show up at a house party

A trendy restaurant in the middle of the dayCanva

A trendy restaurant in the middle of the dayCanva A reserved table at a restaurantCanva

A reserved table at a restaurantCanva Gif of Tim Robinson asking "What?' via

Gif of Tim Robinson asking "What?' via

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva