Lance Armstrong won a record seven Tour de France titles, until this past Monday, when he won exactly zero—he was unceremoniously stripped of his victories, banned from cycling for life, and sent home with his underwear pulled over his head. The verdict had come down from the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, and was quickly supported by the Union Cycliste Internationale, the world’s cycling governing body. As more information is released and more Armstrong-era riders come forward, it appears that Armstrong not only doped, but encouraged doping among his teammates, even supplying them with the necessities.

“Doping” is a term whose ambiguity allows for interesting visuals: Lance under a city bridge, slapping a vein, Lance snorting a line in the back of the team van, Lance sitting on a bare mattress, holding a lighter under a bent spoon.

But doping, at least in regards to performance enhancement, has little in common with this, save for a needle. Many believe that the reason Armstrong got away with it for so long—and why his tests were so often clean—was due to the fact that he was doping his blood with a substance that’s extremely difficult to detect on a drug test: blood.

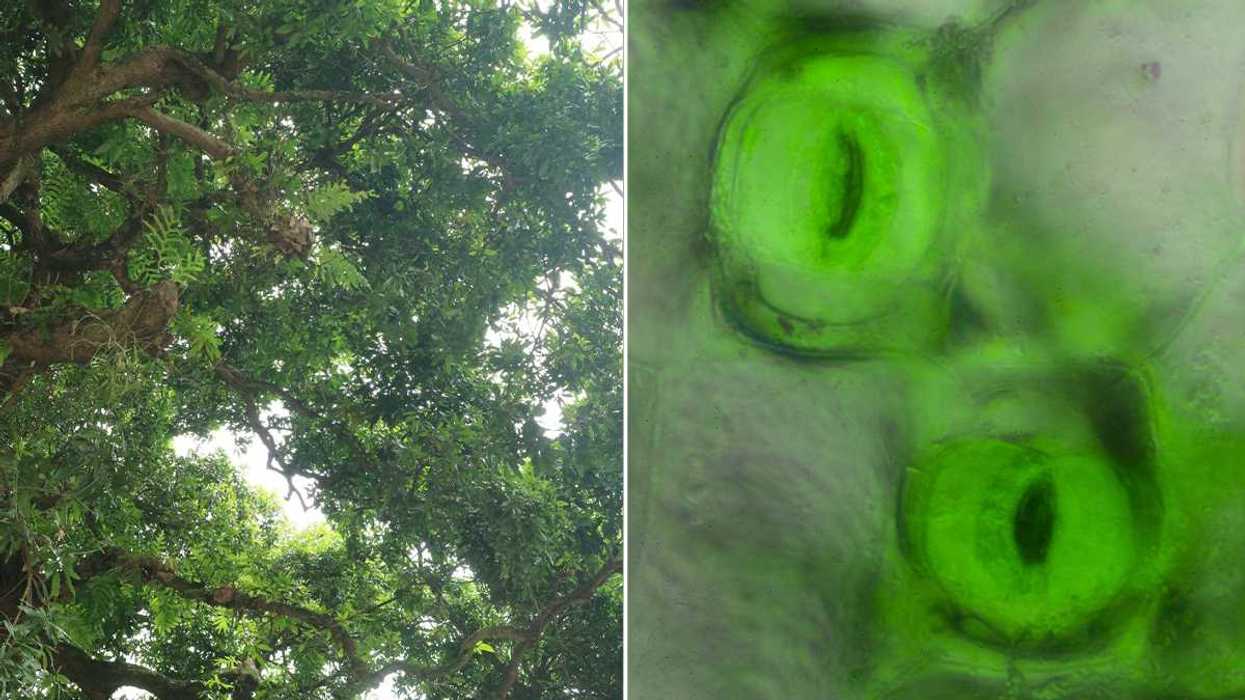

“Blood doping” is a way to increase the number of red blood cells in the bloodstream in order to enhance athletic performance. Red blood cells are responsible for carrying oxygen from lungs to muscles, thus a higher concentration of red blood cells means a higher capacity to carry oxygen, resulting in improved aerobic capacity and endurance.

Increasing the concentration of red blood cells is fairly easy; take blood from a compatible donor or from the athlete well in advance, spin it in a centrifuge to concentrate the red blood cells, and then inject the concentration before the competition. Red blood cells can even be frozen and later thawed with little loss of viability. It’s “au natural.”

One man’s tragedy is another’s triumph, however. Lance Armstrong had rules to play by—the U.S. Military does not. In 1993, Special Forces commanders gave soldiers a small injection of concentrated red blood cells before a mission. These soldiers could run farther, carry more, and stay alert for longer. This “blood loading, ” as the military calls it, is especially effective in high altitude environments like Afghanistan where oxygen is already scarce.

Research and funding into blood loading continues today, and considering its relative ease, safety, and benefit, it may become standard protocol for future soldiers. Unlike cycling, all’s fair in love and war.

Image (cc) flickr user Neeta Lind

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.