Artist Marije Vogelzang has been working with food for more than a decade, but she still finds the subject to be exhaustingly complex. “I don’t think anybody really understands the whole food system,” she concedes. A self-described “eating designer” and teaching artist, Vogelzang combines design with the eating experience in an effort to rewire the way we think about our meals. Through her eponymous studio, two lab-slash-restaurants, a coffee table book, and an eating design department she recently founded at the prestigious Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands, Vogelzang addresses the politics and experience of food for an audience that has grown to appreciate her sensitive, circuitous approach. “When I started,” she says, “everyone was thinking it was about creating beautiful food. ... Now they understand it can be more.”

Recently, she designed a collection of “plant bones,” imagining the shapes vegetable skeletons might take. Her latest project involves partnering with a chicken farmer in the Netherlands who earns his living in a way that Vogelzang finds emblematic of the global food chain’s more incongruous qualities.

Since 2009, a government-mandated program has cut antibiotics fed to Dutch livestock by more than half, a move stemming largely from concern over antibiotic-resistant bacteria incubating in animals and moving to humans once consumed. The farmer Vogelzang is working with has taken that practice to its most extreme conclusion: raising his chickens completely antibiotic-free. It’s an increasingly common practice, even in the U.S., as concerns about such biologically unsound methods grow. Yet this farmer’s primary income involves selling fertilized eggs to other countries, where the chicks are hatched and eventually slaughtered. According to Vogelzang, some of that meat is shipped back to the Netherlands, by which time it has often been pumped full of the same antibiotics her farmer eschewed in the first place. “It’s a really complex and strange thing,” the 36-year-old artist says.

Vogelzang is aware of how knotty the global food system can appear, particularly to ordinary citizens unfamiliar with its intricacies. In the course of a phone call from her home in the Netherlands, she frequently references what she considers a major problem in the way food is produced, consumed, and experienced: “A lot of people in the food system are specialists. It can be really hard to look beyond those specialisms.” Individual tweaks to the system, she thinks, may not be enough. As she plans to demonstrate with her still nebulous poultry project, Vogelzang believes it’s possible to improve the food industry if we—farmers, line cooks, and grocery shoppers alike—think critically about our culinary habits.

In her internationally exhibited installations and art pieces, Vogelzang creates experiences that upend what she considers thoughtless eating rituals. In Budapest, Roma women feed visitors while telling them their life stories. In Tokyo, shoppers’ memories of rice are printed on rice bags and taken home by strangers. In Milan, Tokyo, Rotterdam, London, and New York, a pop-up café serves labor-intensive food—hand-pressed orange juice, personally whipped cream—cooked and served by seniors. In some cases, the farther away a dish’s ingredients were produced, the smaller the plated portion. For one Christmas dinner that Vogelzang designed, she hung tablecloths from the ceiling, cutting holes so that only diners’ faces and hands were visible to the table. For another project, she created the “pasta sauna,” a steam-room-slash-spaghetti-cooker in which the dining environment is meant to match the intrinsic quality of the food. These projects could either be interpreted as art in the service of social commentary—the message being: consider what enters your mouth more carefully—or high-design versions of supper clubs in which “slow food” applies to both the means of production and the ritual of eating. In any case, Vogelzang’s intent with these elaborate food-art experiences is to rewire eating customs by reorganizing meals in a way that erases our most deeply ingrained habits.

Accordingly, the artist and her team have also redesigned snacks for schools by color-coding them, an attempt to get students away from the associations they’ve acquired in their short lives—for example, that green is healthy and therefore gross. They’ve also consulted for hospitals, where they found that cutting food into smaller pieces encourages malnourished patients to eat more.

With Vogelzang’s “Food Non Food” department at Design Academy Eindhoven now in its second year, the artist is intentionally vague about her hopes for future alumni. The program, which last semester sent students to slaughterhouses, farms, and food retailers, will in the coming months focus on bio-art—Vogelzang cites designer Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s explorations of the ethics of lab-grown meat as one major inspiration in this arena. She says the industry—and an interest in sustainable, ethical food practices—is changing so much, her program may prepare students for a future in which “there are new jobs we just don’t know of yet.” Still, she has faith that the “strange design twist,” “the creative vision that changes the way something works,” will prove useful when it comes to reorienting how food is grown and consumed. Vogelzang ticks off a few specific problems: our level of meat consumption, the lack of biodiversity in the soil, and that our “seas are getting ruined.”

Even in the last decade, says Vogelzang, “the openness for this kind of work is greater,” and with the creative class clamoring for organic meats, slower food, and heirloom vegetables, it’s clear that there is a market for her brand of playful, sustainability-inflected design. Appealing to the broader public is often questionable with high-concept design, but the artist remains hopeful. “I think when you look back into history, all changes to food culture happened in a kind of elitist niche,” she says. “Small things”—multi- course meals, silverware—“are adopted by a bigger group. It eventually spreads.”

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

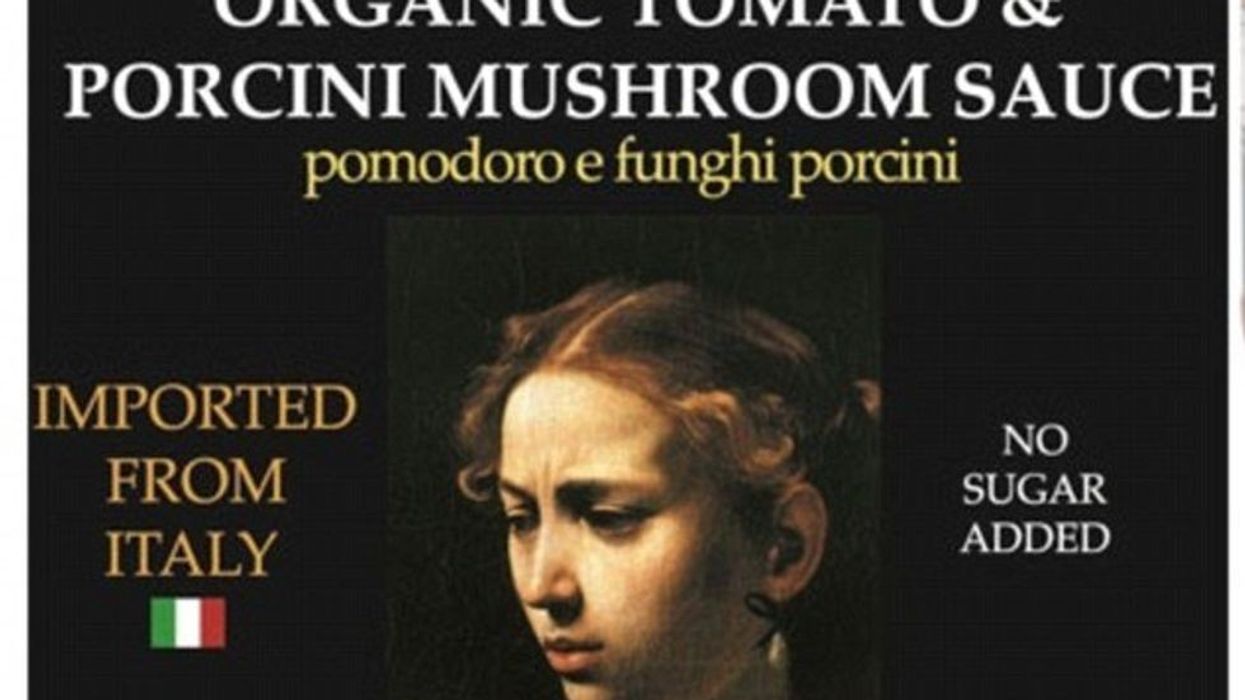

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)