“Do you know what the word ‘taboo’ means in its root context?” I don’t, but I have a feeling Miki Agrawal is about to tell me.

“‘Taboo’ stems from the Polynesian root word ‘tapua,’ and do you know what ‘tapua’ means?” she asks, not waiting for an answer this time. “Menstruation.”

Agrawal pulls this piece of trivia out of her pocket triumphantly, attempting to drive home the unease in patriarchal societies when it comes to talking about, and dealing with, periods. As the inventor of Thinx, the “period panties”—which absorb menstrual blood and preclude the necessity of tampons or pads—Agrawal experiences no such discomfort.

The 37-year-old entrepreneur and her sister, Radha, came up with the idea for Thinx at a family reunion. “It took us three and a half years to develop the product, working with textile technologists, working with anyone who would listen,” she says.

“A lot of these technologies exist, but they’ve never been used for the most intimate part of a woman’s body. I got a lot of hang-ups in my face.”

When Thinx launched in 2014, it attracted press attention that skewed largely adulatory. The underwear—made of a special fabric blend that is antimicrobial, stain-resistant, and leak-proof—didn’t just provide a solution to a problem many women face monthly. The product also latched onto a wider conversation about menstruation that was starting to pick up steam internationally.

In 2015, we couldn’t stop talking about periods. Whether it was period art—both cringe-worthy and profound—or the “tampon tax” protests that were taking place outside the hallowed parliamentary halls of Australia and the U.K., the subject of menses was in the spotlight. Early in the year, Canadian poet and artist Rupi Kaur lodged a protest against Instagram after the social media site removed photos from a series she created depicting the menstruation process, blood stains and all. Instagram eventually bowed to pressure and reinstated her post.

[quote position="full" is_quote="false"]For as long as women have been bleeding, there has been a man standing somewhere nearby, primitively grunting to signal his disgust.[/quote]

Later in the year, Kiran Gandhi, a drummer and music industry consultant, made headlines when she “free-bled” while running the London Marathon in April to challenge the stigma of menstrual blood and to raise awareness of those who lack access to sanitary products. When the Daily Mail published photos of her mid-race, they censored the dark stain between her legs, underscoring Gandhi’s point.

Now activists are even bringing menstruation to the forefront of economic policy discussions, staging campaigns around the world to eliminate consumer taxes on feminine hygiene products. They succeeded in Canada, where the government responded to pressure by repealing the tampon tax. In the U.K. and Australia, however, tampons continue to be taxed as “luxury goods” or “nonessential items.”

Agrawal, too, found herself at the center of a period-related controversy in 2015, when the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) advertising contractor, Outfront Media, rejected a series of Thinx ads slated to run in New York subways. The posters featured a halved grapefruit and read: “Underwear for Women With Periods.” Outfront Media told Agrawal that she had to make changes to the copy before they could approve the ads. Agrawal refused, and went to the press instead.

“It was really wild that even the word ‘period’ was not acceptable in the subways because the advertising industry, or at least the signage industry, is run by old white guys,” she says. “The only way we got them to approve the ads was because it got enough press and angry tweets. You can use grapefruits to show augmented breasts, but you can’t use grapefruits to show something that occurred naturally?”

The stigma of menstruation is one that has survived thousands of years of human history and progress. For as long as women have been bleeding, there has been a man standing somewhere nearby, primitively grunting to signal his disgust. In ancient Rome, women were believed to acquire the magical ability to stop hailstorms or halt lightning during their monthly periods. Menses could render crops “barren” and drive dogs “mad,” the Roman author Pliny the Elder wrote in his 1st-century encyclopedia, Natural History. The Victorians viewed menstruation as an illness, and women were confined to private quarters during their periods. Victorian etiquette, in fact, prohibited any discussion or mention of the fact that women bled at all. Even today, representations of menstruating women in popular Western culture frequently trade in stereotypes that depict them as mercurial or volatile.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]It was really wild that even the word ‘period’ was not acceptable in the subways because the advertising industry, or at least the signage industry, is run by old white guys.[/quote]

These persistent ideas about periods—what they are, how they affect women—aren’t just offensive. They’re damaging to women. In the United States, homeless women often go without hygiene products because aid agencies forget altogether that the need exists. Elsewhere around the world, young girls are prevented from going to school while on their periods, because they don’t have access to pads, or because they’re considered unclean. A few years ago, Agrawal was visiting South Africa, and spoke to a young girl who told her that her “week of shame” prevented her from attending school. “I realized that feminine hygiene or menstruation management is a root cause of cyclical poverty,” says Agrawal. “So I came back super angry and pissed off.” Now, for every pair of Thinx someone buys, the company sends money to AFRIpads, a Ugandan organization that trains women in developing countries to manufacture and sell reusable sanitary pads to local women.

It’s a philanthropic model she uses for all her businesses. She also has launched Icon Undies—underwear for women who experience leakage when they sneeze or laugh, sales from which benefit the Fistula Foundation. And this year she’s working on Tushy, an easy-to-install device that turns toilets into bidets, which will send funds to the nonprofit group charity: water. If it appears that Agrawal has a fixation on all the things that happen below the waist, it’s because she does. “All I’m going to be focusing on for the next several years of my life is peeing, pooping, and bleeding,” she says.

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

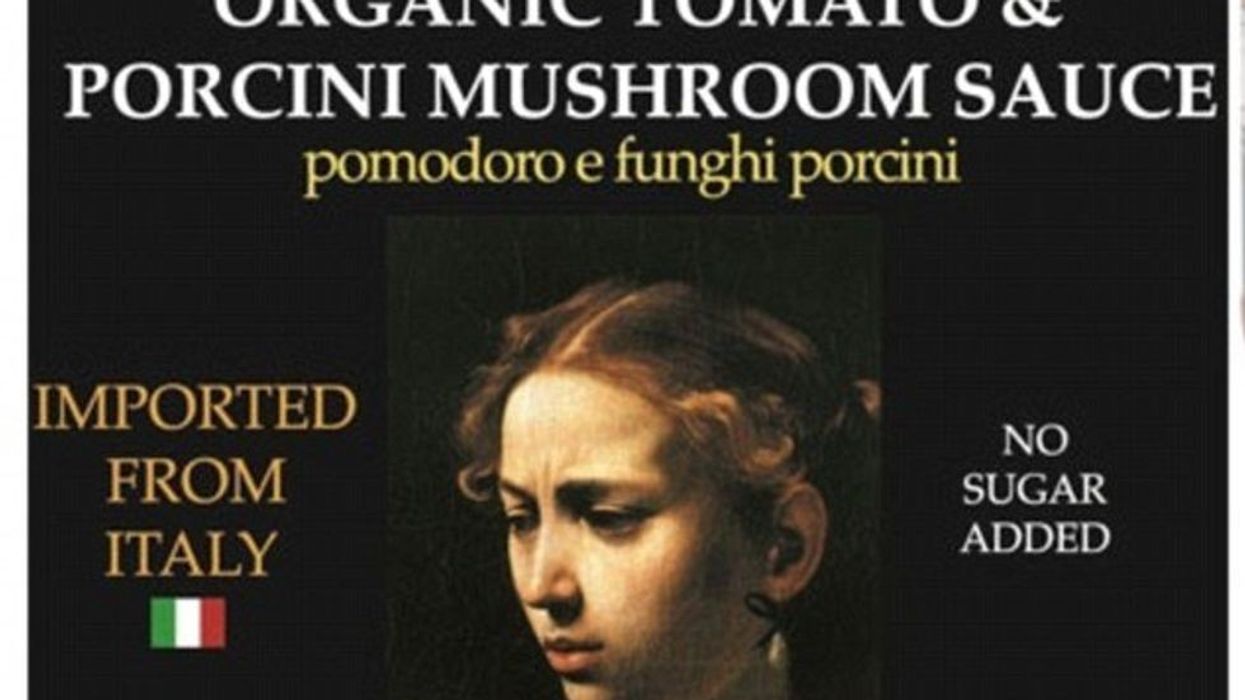

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)