IT WAS NEW YEAR’S EVE, AND EVERYTHING WAS SUPPOSED TO CHANGE. A number of local friends came over to my apartment in Istanbul, where we toasted the end of 2016—the bloodiest year in Turkey’s recent history. At midnight, a woman named Ozum screamed with joy: “Thank God it's over.” Moments later, my WhatsApp erupted with panicked messages from acquaintances who were barhopping that night. A deadly attack had taken place at a nightclub called Reina, a short drive away. I rushed to the scene to report on the terror incident for USA Today.

I remember the rotating drum of red lights from the ambulance parked outside, along with a man weeping so stiffly he choked. But what lingers most strongly may be two women in their 20s lurching out of Reina, the first carrying her wounded friend using one arm; she used the other to support her own injured knee. Together, the pair limped urgently to get out of the frenzy. I hurried to help them and pressed a water bottle to the injured woman’s mouth so she could drink. She smiled and said “Tashakula” (thank you).

Once one of the world’s great empires, Turkey—which shares its largest border with Syria—is a member of NATO, and just four years ago was hailed as a model of democracy by a number of world leaders. The European Commission, which had been considering Turkey a candidate to join the European Union for years, released a positive 2013 progress report commending the nation for a democratization package, judicial reforms, the establishment of human rights institutions, peace processes, and more.*

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]We’re suspicious of what might lurk around the corner, overly grateful whenever nothing has gone wrong. [/quote]

Since then, internal politics and regional meddling by Turkey’s sitting party have caused the EU to reconsider its democratic values, freezing its membership process. The nation’s then-Prime Minister, now President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has been consolidating power for himself, making new alliances only to abandon them, working to instill fear and a lack of trust within his nation so severe that even an attempted military coup last July hasn’t stopped him.

On Sunday, April 16, Turkey will hold one of the most important votes in its history: whether or not to relinquish a parliamentary democracy in favor of an executive presidency (essentially a dictatorship). If the polls are to be trusted, those in favor of democracy are losing, and the predicted outcome will set a precedent for authoritarian rule that may irreparably disrupt the Middle East and possibly much of the West, as well.

Since he was elected in 2014, Erdogan has veered down a dangerously tyrannical path, hunting down so-called “terrorists” against the state, arresting and imprisoning tens of thousands of journalists, human rights activists, lawyers, and security officials, paralyzing national institutions and throwing nearly everyone—whether they support Erdogan or oppose him—into a near-constant state of panic.

Turkish citizens are alert at all times, suspicious of what might lurk around the corner, overly grateful whenever a stretch of time passes and nothing has gone wrong. Each time I see him, my grocer says things like this to me: “Thank God you were not hurt at Reina.” A few weeks later, after a car bomb goes off at a courthouse: “Thank God you were not in Izmir.” The following month, after a suicide bombing at police headquarters: “Thank God you were not in Gaziantep.” Then we nod at each other, rather than acknowledge our shock that we’re both still alive aloud.

“There is something about living in fear that I don’t trust,” says my good friend and psychologist Pinar Din, who at 41 has so far been successful in keeping her 2017 resolution to practice making scrambled eggs and learn how to swim. Ordinary life is her resistance. “There is something wrong with silently fearing something. I think we should speak out every time we don’t trust something we are told.” Pinar often comes by my apartment to seek a couch from which she can furiously type notes to friends, nudging them to participate in a protest. “We must ask, ‘Who is a terrorist? Why can’t the government protect us from them? Why are so many people in prison?’” she writes. “We should ask until we find clarity.”

Elif Kaya, a 36-year-old who runs a coffee shop in the hip Istanbul neighborhood of Cihangir, is also suspicious of her government for not prioritizing the safety of its citizens. “Erdogan is not doing anything for his country. He just wants to draw power for himself,” she says. “Even if there are terrorists who hurt us, it is the government’s job to protect us.”

What I saw at that massacre taught me a lot about what’s at stake for the Turkish government, its people, and for democratic countries with populist leanings, including France, Britain, and the United States. Ozum later told me she was stunned that the new year didn’t bring new tides as she’d expected, instead snatching away any reassurance she had that instability would be over soon. For me, what has remained is the person who remembered to say “thank you” in a crisis. Even in daunting times, when our long-standing democratic protections do not hold, there’s plenty of reason to keep faith in our power to resist.

As Sunday’s vote approaches, people rush to ferry boats as if the fear of crowds has completely vanished from their minds. There’s an old saying here in Istanbul, a city of 15 million tobacco-chewing artists and builders who cross its historic bridges over the Bosphorus Strait every day; parents taking their children to graffiti-dotted playgrounds, pedestrians hopping into taxi cabs during rush hour to race to work, and fishermen toiling beneath them just before dawn: “We are the bridge people, and for some reason everyone knows that everybody will pass through.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]Even when democratic protections do not hold, there’s plenty of reason to keep faith in our power to resist.[/quote]

My journalist and writer friend, 43-year-old Ece Temelkuran, puts it more simply: “There is a wisdom in this country, to wait for things to be over.” I fear that if those who want to resist Erdogan do not come out to vote, waiting for things to pass could be their only option.

Of course, being patient is, in its way, a form of resistance, or at least resilience. It reminds me of chewed tobacco—wretched and somehow beautiful, too. Having spent more than two years in and out of Turkey, traveling through its oft-forgotten Kurdish towns along the border, witnessing the flux of refugees from Syria and elsewhere, I can say that the country offers a case study about what can happen when we allow those in power to increase their strength too quickly. But, depending on what happens on Sunday, it may also reveal what’s possible when citizens fight back.

Volunteers at the St. Francis Inn pray together before serving a meal on July 19, 2021.

Volunteers at the St. Francis Inn pray together before serving a meal on July 19, 2021. Police close down a section of Kensington Avenue to clear a homeless encampment on May 8, 2024.

Police close down a section of Kensington Avenue to clear a homeless encampment on May 8, 2024.

Left: A robotic arm. Right: Rice grains.Photo credit:

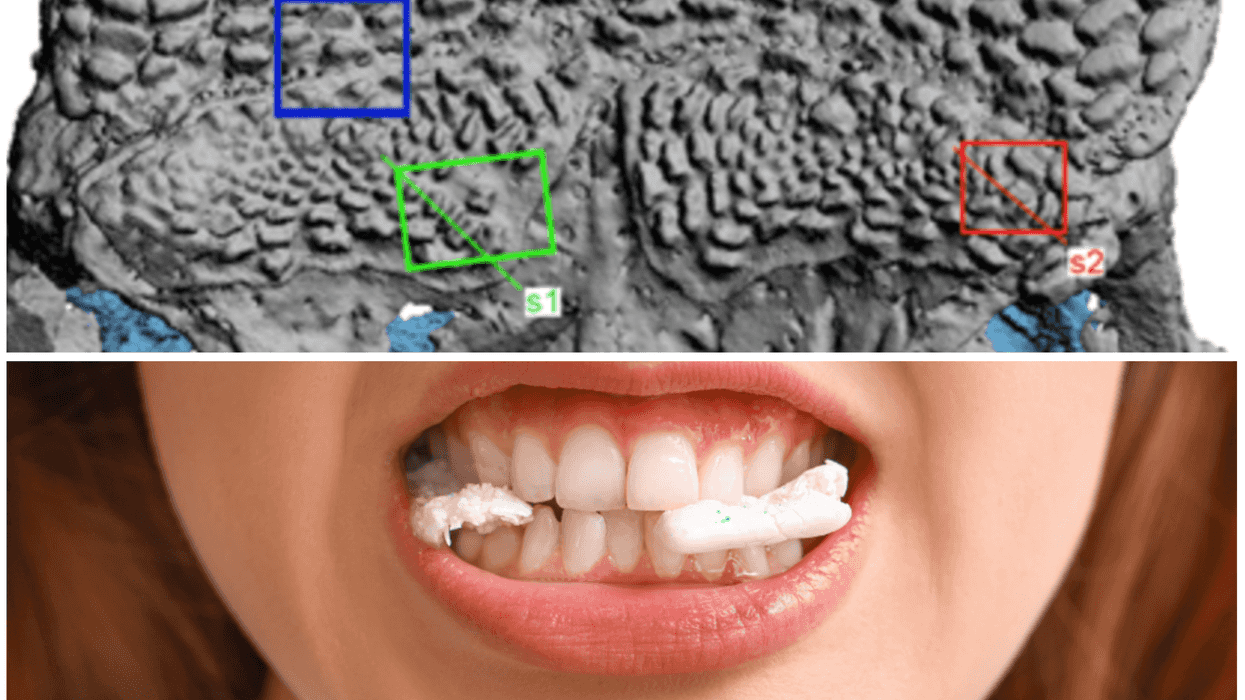

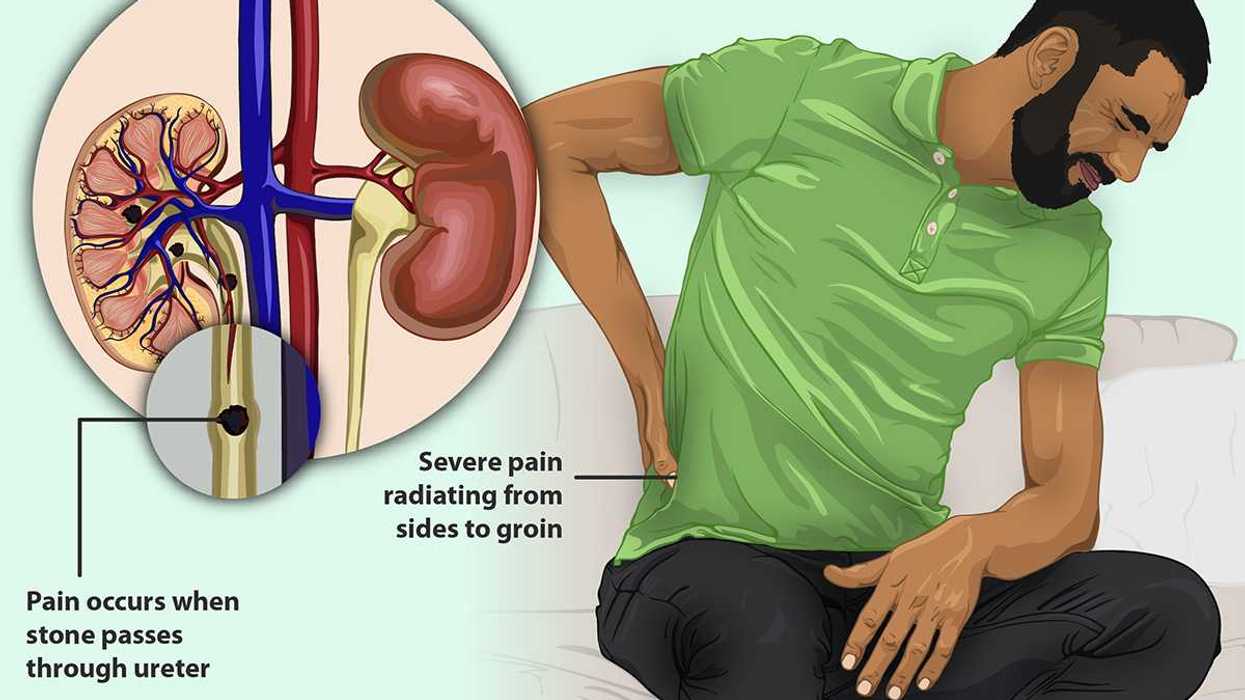

Left: A robotic arm. Right: Rice grains.Photo credit:  A diagram on kidney stones.myupchar/

A diagram on kidney stones.myupchar/

A couple engages in a serious conversationCanva

A couple engages in a serious conversationCanva

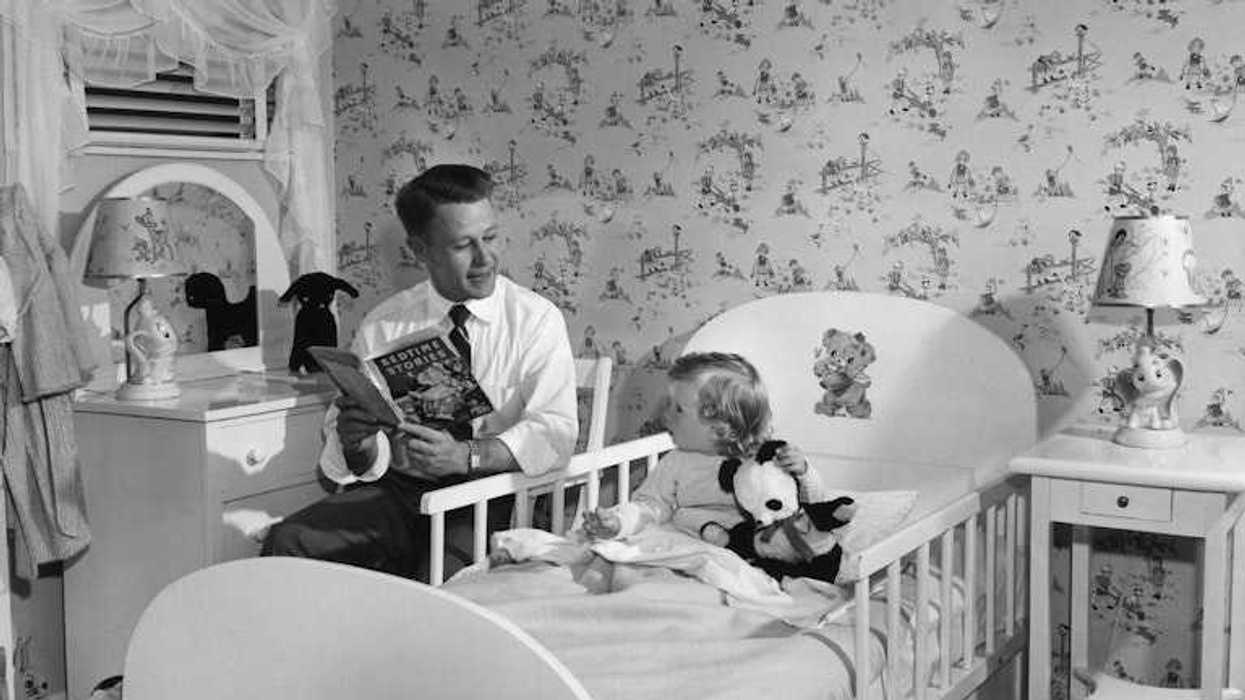

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025.

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025. Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.

Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.