In 2009, music journalist Yancey Strickler stood in the packed audience at Brooklyn’s Monster Island venue and caught an inspiring performance by the San Francisco rock band Girls. Strickler had liked what he heard and so he approached the band about releasing their first single “Hellhole Ratrace” digitally, through his micro-imprint eMusic Selects. Before too long, Girls had become a critically adored band with a coveted Best New Music-designation on Pitchfork, sold-out nationwide tours, and received coverage in major magazines like Vogue and Rolling Stone. Even back then, Strickler believed that it’s one thing to appreciate the arts, but it’s another thing to be actively involved in them.

And now, years later, Strickler, along with his two partners Perry Chen and Charles Adler, has made a business out of patronage. With the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, just about anyone can be as actively involved in the arts as Strickler was, by, for example, supporting and investing into something as admirable as an Academy Awards nominated documentary or helping relaunch the educational Reading Rainbow program, to funding feats of pure silliness like the bronzing of a bunny sculpture in San Francisco’s Lower Haight neighborhood or backing a dude determined to make his first potato salad (the latter, incidentally, raised $55,000).

The CEO and co-founder greets me in one of the sun-drenched conference rooms in the company’s new Greenpoint, New York location. Our interview comes at an important time in the startup’s history: Among the many things we have to discuss—one of them being the aforementioned potato salad undertaking which ostensibly only succeeded because of the new lax, if not inexistent, review process—Kickstarter is in the process of expanding its reach while also maintaining its organic community-feel. A contradictory move to many, inciting the most zealous of us to start brandishing the red ink “sellout” stamp. However, despite this pervading sense of it all becoming crass consumerism when marquee names like Spike Lee or Kenny Loggins launch a campaign, Strickler, whose indie roots are well established, really seems to be the perfect person able to maintain the Kickstarter philosophy no matter how big they get. Which, ultimately, goes back to that summer night in 2009, when a young Village Voice writer saw a band he believed in and did his part in bringing their music to the masses.

How did you move from writing about music to being a startup entrepreneur?

I wouldn’t categorize myself as a natural entrepreneur. I’m just someone who has thought of ideas and followed through on them. I started a zine in college, started a really ridiculous baseball website that was popular for a minute, and then when I was at eMusic, I started a record label. It was called eMusic Selects, and I would go to shows, see baby bands and try to put out their CD-Rs. Out of that, we put out the first High Places record, the first Crystal Stilts, the first Best Coast, and the first Girls’ single. And it was just me seeing interesting things and feeling like I had a pulse on what was good. But that was the first time I was actively involved in creating something and shaping it. This was happening concurrently while Perry and I were talking about Kickstarter. That gave me a bit of a bug, and in my day job, I started exploring that a little.

So you’ve always had a desire to incubate?

It’s sort of like that, but all I ever wanted was to be a writer when I was growing up. Same with one of my best friends, who now runs a coffee roasting business. We talk about the fact that we became objective business people and how weird that is. Maybe this is just an American way to explore trying to shape things in the universe. Like I have a point of view of the world, and wanted to actively be a part of it. And as I’ve matured and gotten to know myself better as a person, I’ve become more aware of that. I care about music and culture and I always wanted to be a writer, wanting to highlight what I thought was the vanguard of really quality work, and then trying to create Kickstarter along with Perry and Charles—I see both of these efforts as the same thing in a sense.

As a former writer and champion of the arts, is it possible that you’ve seen how difficult it is to maintain a creative career, and maybe subconsciously you’re now doing everything you can to help actualize other people’s visions?

It is possible. Perry had the idea initially from a personal experience. For me, it was once removed. When I was working in the music industry, there was a lot of conversation about how we could monetize it. But there was no conversation about where the music came from, what it took to make a record, or what the various obstacles were that you had to surpass. The industry treated music as an infinite resource that would always flow through, as if it was only a matter of selling it.

I was always witnessing what my friends and the bands I loved were going through, and even watching what David Lynch had to go through to make a movie... I knew that the real challenge was far earlier in the process, and this was being ignored. Kickstarter came about because of the problem that most creative people experience, and things like box office numbers... that’s a business problem, not a creative problem. A lot of it came from questions like: Why aren’t people looking earlier? Why aren’t people looking at how things are actually getting made? It’s just presumed that there will always be a steady output of culture and that the culture industry will always produce. And there are parts of the industry that will keep doing that. But there’s other parts that are constantly living on the edge, and how things get made under those conditions is miraculous because it’s a real test of will.

We were just thinking about the problem in a different way.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]I have no qualms about more established people using Kickstarter because it’s a tool that helps people create… I’m totally empathic to the response people may have to celebrity campaigns, but it’s open to everyone.[/quote]

Based on that thought, I’m curious if we can get specific in discussing the future of the music industry and how instrumental Kickstarter will be to it?

I don’t know if we will be. But I think there are six industries that have changed since Kickstarter launched: indie films, video games, product design, hardware, comic books, and dance. Music, I would not put in this list. I think that the cost production for music is a lot lower. There’s more you can do with music with less money. And I think the biggest currency in music is “cool.” Like that’s it. You want to be mysterious. The transparent musician is a space that few people can occupy, like Amanda Palmer and ?uestlove maybe. And those musicians stand out. But most of the others benefit from being somewhat removed. Kickstarter is very transparent, and you are very much out there so it doesn’t work as effectively in maintaining coolness.

I think that for those reasons the music industry’s response has been very different from the ones made by the game and film industries. And to be honest, I think the future of the music industry is the same hodgepodge we see now. Musicians will look to brands to help fund them, which has been a strong source of revenue for 10 years and will work for cool music. But that being said, if you’re not making cool music, you’re in a tougher spot.

Speaking of cool music, I see you backed Kenny Loggins on Kickstarter.

I did back Kenny Loggins.

How do you make sure that the brand remains a tool for regular people? What happens when guys like Kenny Loggins are the dominant campaigners on Kickstarter?

Many more people are backing projects other than Kenny Loggins’. It just so happens that Kenny Loggins on Kickstarter gets a lot more press. They get a lot of press attention because they’re celebrities and that naturally comes with the status. I think the impact is more on perception because of media than on the website itself. I have no qualms about more established people using Kickstarter because it’s a tool that helps people create. I have seen reactions to these kinds of projects and there’s a presumption that people will automatically back it because they see a shiny celebrity involved. But I think people who are making the decisions are very smart and have discerning tastes. People know what they want and what they don’t want. So I don’t see any conflict with this. I get that since money is involved it ratchets up the apprehension, but this is never a question people would ask when a celebrity joins Twitter because Kickstarter is the people’s space. And I like that people feel protective of it. It’s a positive thing. I think that says something great about what we’ve accomplished so far, Kickstarter is a tool for all and that’s what we’re all about. I’m totally empathic to the response people may have to celebrity campaigns, but it’s open to everyone.

I’d like to talk about the changes that were made at Kickstarter earlier this year. Will they impact the brand and dilute the quality of projects?

Well, what do we care about? We care about creative projects, about enabling them, about making them possible. This considered, a mandatory review process, doesn’t seem to be in the service of the creativity. When we looked historically, we found that 80 percent of the projects were being approved anyway, so why make these people wait in line for the 20 percent of projects that weren’t being approved? That, and the Potato Salad thing has brought tremendous growth to us.

You see the Potato Salad stunt as a good thing for Kickstarter?

Yeah. You would look at that project in a completely different manner had it not gone viral. It’s all about context. The very first successfully funded project was called Drawing for Dollars and it was this guy who said if you would give me $5, I’ll draw you something. I don’t think that Drawing for Dollars and Potato Salad are that dissimilar.

Well, with Drawing for Dollars, you got a picture, but with Zack Brown’s Potato Salad, you got nothing. He made a potato salad and didn’t share it with you.

What I think about Potato Salad is that it communicated to people that there really is accessibility to creating something. Projects have become bigger in terms of time and more mega overall in the last few years. Some of them have been very serious undertakings. Do they possibly intimidate people from wondering: “Here’s an idea that I’m going to float to the world and see what happens.” Certainly Potato Salad asks questions about brand identity, but it also says a lot of things about fun. I would rather have that much more nuanced identity when seriousness and frivolity can live side by side. If you had asked me two months ago whether a project like Potato Salad would have shifted the conversation about Kickstarter, I would have been very confused.

It may have even done Kickstarter a service?

It’s not a purely good thing. It brings questions as well to sort through. But there were a lot of positives.

You talked about the 80 percent of the projects that were approved but let’s talk about that other 20 percent. I’d like to hear about those potentially controversial projects falling through the cracks.

The shift in workflow is really about: “Let’s make sure people with great projects don’t go through speed bumps with us.” A lot of it was small print and we were asking how much of this is really necessary. The things that are not permitted now are small things, they’re rounding errors. But the website is pretty much the same. Same philosophy, same values. I hope the fact that we changed the rules makes Kickstarter a more inviting place. I want everyone to feel welcome, and I don’t know if everyone in the past felt that way. For the past three years, we went through every project, but for the first two years, we did not. This is, in a way, a return to where we were.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]If you had asked me two months ago whether a project like Potato Salad would have shifted the conversation about Kickstarter, I would have been very confused.[/quote]

When the announcement was made about the new rules, people warned of scams. Are scams possible?

Sometimes things will get labeled as scams, but we’ll stop it before it happens, and no money will trade hands. I have no examples of verified cases of people committing fraud.

Is it a concern of yours that some campaigns have a flashier presentation with high budget videos, which inadvertently may reintroduce that intimidation factor?

I would love to put more of a light on things that are more amateur. We don’t have the resources for that yet, but we would love to eventually move in a direction in which, say, someone shot something on their iPhone and we could be involved in bringing it the attention it deserves.

Do you think Kickstarter has made people more entrepreneurial?

Yeah. How many people looked at the Potato Salad guy and thought: “Man, I gotta do something.”

So, I can look forward to the Cole Slaw project?

Those happened. And they didn’t get funded. We have a brilliant mechanism that’s core to the design in which the public decides what gets funded. Each person decides on their own. So no, I don’t see a grave moral danger in Cole Slaw.

We talked about music, and culture as a whole. But once the product is made, we still have a problem with distribution and marketing? How do you solve that problem?

Well, that’s again what the music industry focuses on; the distribution of something that already exists. But our inspiration was to focus on the first part. We’re addressing the part that inspires me, and a lot of people that work here.

As a former journalist, what’s it like being interviewed?

It’s great. It allows me to articulate what I’m thinking.

And how was your Charlie Rose appearance?

Wild. That was a very intense experience. We never expected Kickstarter to be as successful as it has become. And truthfully, patronage existed before Kickstarter. We didn’t invent it. The first example of Kickstarter before Kickstarter that I can mention is a translation of the “Iliad” by Alexander Pope from Greek to English in 1713, I think. He got 750 subscribers to pledge support and they all got their names printed in the first edition.

I think a lot of people admire the Kickstarter brand because of how protective they are of it. How do you maintain that relationship even when a brand gets to be as large as you’ve become?

I think it’s being honest. People understand that there is a true spirit, at the center of all of this.. How do we apply that old spirit to the new challenges that come up? I think people have a decent albeit vague sense of our integrity and what that spirit means.

What Kickstarter project would blow your mind?

Probably one created by David Lynch. I think that would mean a great deal to me personally if he hosted a campaign on the site.

Winter weather.

Winter weather.

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from  A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from

A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from

Siblings engaging in a pillow fightCanva

Siblings engaging in a pillow fightCanva

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

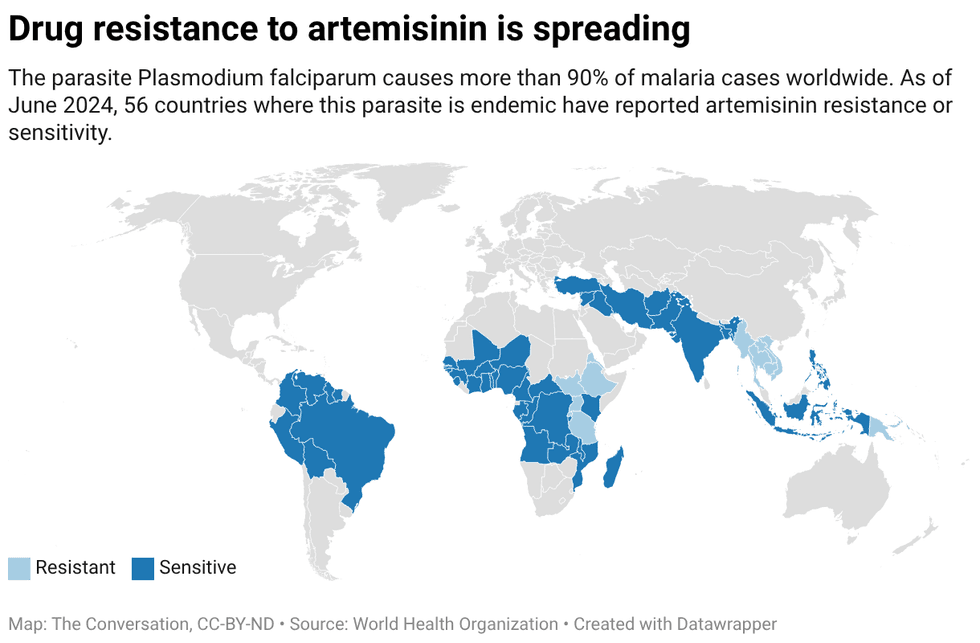

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Created with

Created with  Where to turn off autoplay in your account on Facebook’s website.Screen capture by The Conversation,

Where to turn off autoplay in your account on Facebook’s website.Screen capture by The Conversation,