Editor's Note: GOOD's parent company is a proud partner with Global Witness, sharing stories of their mission challenging abuses of power to protect human rights and secure the future of our planet.

There's one major oil corporation that touts itself as, "the human energy company." Like many good slogans, the meaning deepens with double-entendre: "human" serves as an adjective twice, both to humanize their business, and describe the kind of energy in which it deals: human energy. People power. The stuff of "creativity and ingenuity."

The company in question is, of course, Chevron, and—as a brief scan of their website reveals—they're really into this "human" angle. On their homepage alone, they offer up lines like, "it's only human to want a better life," "powering human progress takes energy," and, "our greatest resource is our people."

That sounds nice. But if behind the scenes, a company continues to pollute and fail safety measures, funding politicians who roll back pro-environment policy and questioning climate change, the slogan acquires a darker tinge. If a company that prioritizes profit over public health it doesn't generate human energy so much as consume it—depleting the original source.

For a salient example, look no further than Richmond, California, Chevron's home base since 1902, where health conditions disproportionately impact residents. According to a recent Global Witness report, Children have roughly twice the rate of asthma as in neighboring areas, and communities bordering Chevron's facility are in the 99th percentile for respiratory illness. Organizers have long fought for their health and safety, battling in the courts to try and hold Chevron to account for pollution violations and failed safety measures. But Chevron remains largely impervious, arguably because of the political and legal influence they buy.

Despite claiming to protect the environment, Chevron continues to fund senators with overwhelmingly anti-environment voting records—politicians both dismissive of new green initiatives, and working to dismantle those already in place. Take Sen. Martha McSally, for example, who admits only to a "likely" human effect on climate change, and denies the connection between fossil fuel emissions and global warming. Or Sen. John Cornyn, who acknowledges climate change is real, but consistently votes as though, "it's a big hoax." How meaningful is Chevron's support for the Paris Agreement, when they support politicians who nominated Andrew Wheeler, a former coal lobbyist, to the EPA? A man who has moved to "dramatically weaken," climate change initiatives designed to curb emissions?

The oil major also operates in what can be viewed as insidious ways, perpetuating climate disinformation, and accusations of environmental racism. Just last month, according to the same Global Witness report, E&E News revealed Chevron was likely behind a public relations scheme to convince journalists to push the message that environmentalists advance "radical" climate policies, such as the Green New Deal, that would hurt minority communities. But some argue minority communities can't be the real concern—more than 80% of those pollution-sickened Richmond residents are people of color.

You can see the bind Chevron's in: the oil industry's business model is still heavily reliant on practices that contribute to dangerous levels of climate change. They have admitted, "Regulations designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions might also render the 'extraction of the company's oil and gas resources economically infeasible.'"

The overwhelming scientific evidence states that climate change is real. That's a truth that must be faced, immediately, not endlessly delayed and distorted to perpetuate an increasingly untenable status quo.

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |  Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva A female artist in her studioCanva

A female artist in her studioCanva A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva

A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva  A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva

A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva  A woman flexes her bicepCanva

A woman flexes her bicepCanva  A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva

A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva  Two women console each otherCanva

Two women console each otherCanva  Two women talking to each otherCanva

Two women talking to each otherCanva  Two people having a lively conversationCanva

Two people having a lively conversationCanva  Two women embrace in a hugCanva

Two women embrace in a hugCanva

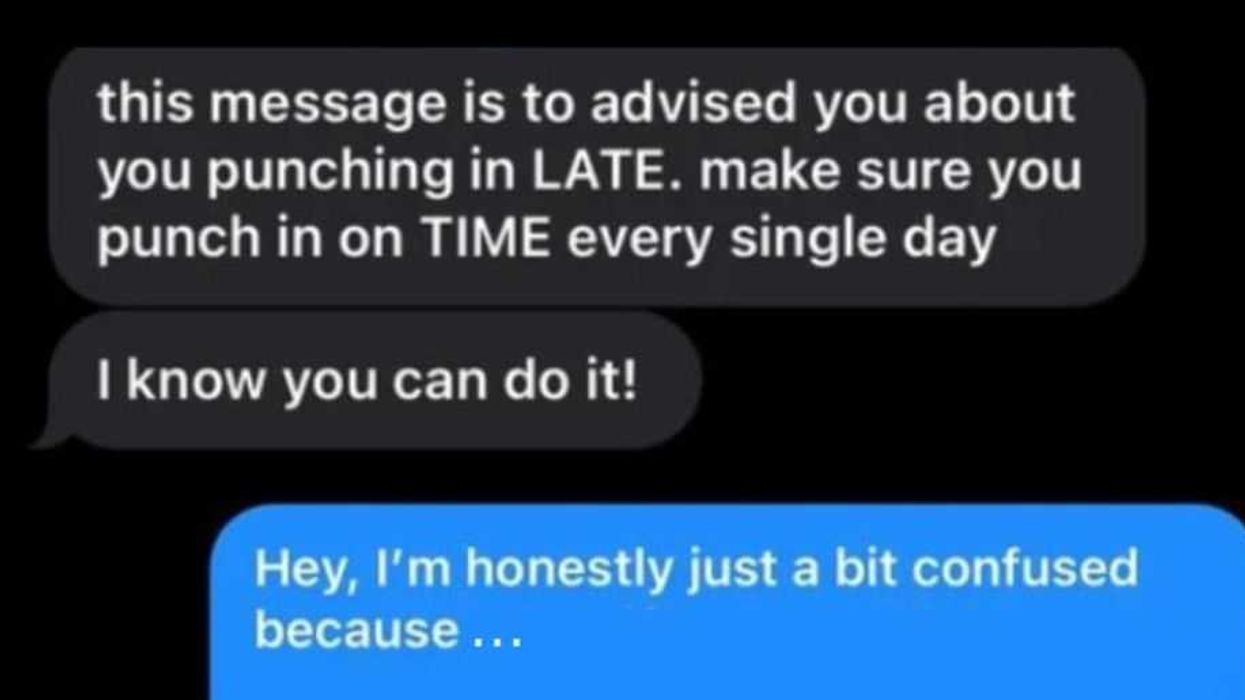

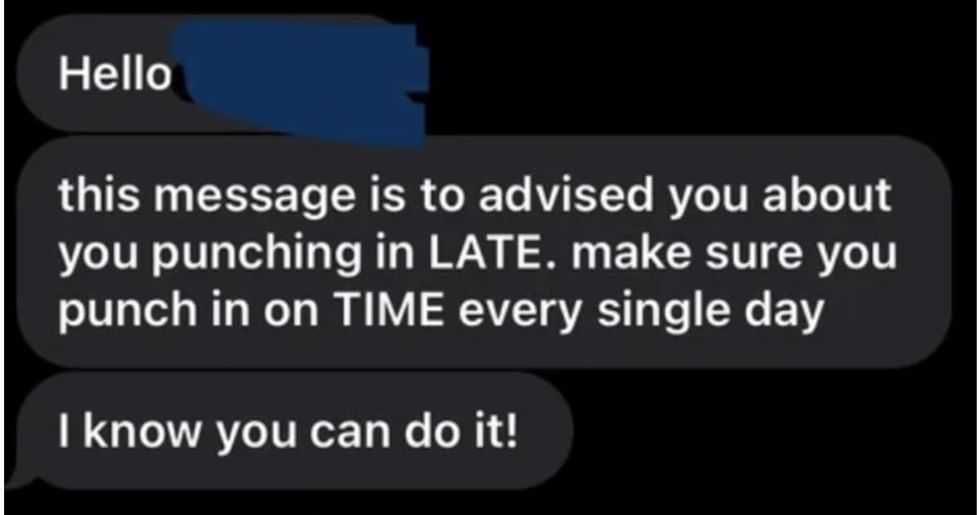

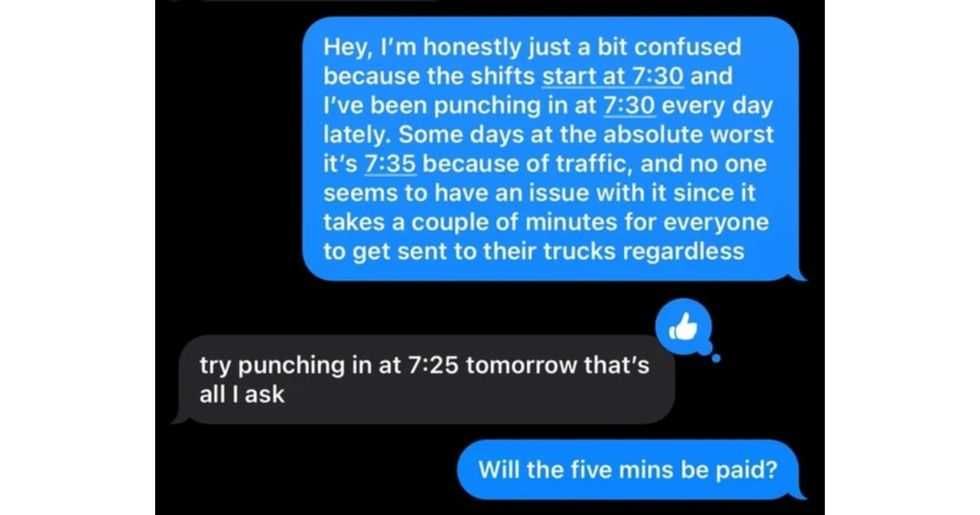

A reddit commentReddit |

A reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

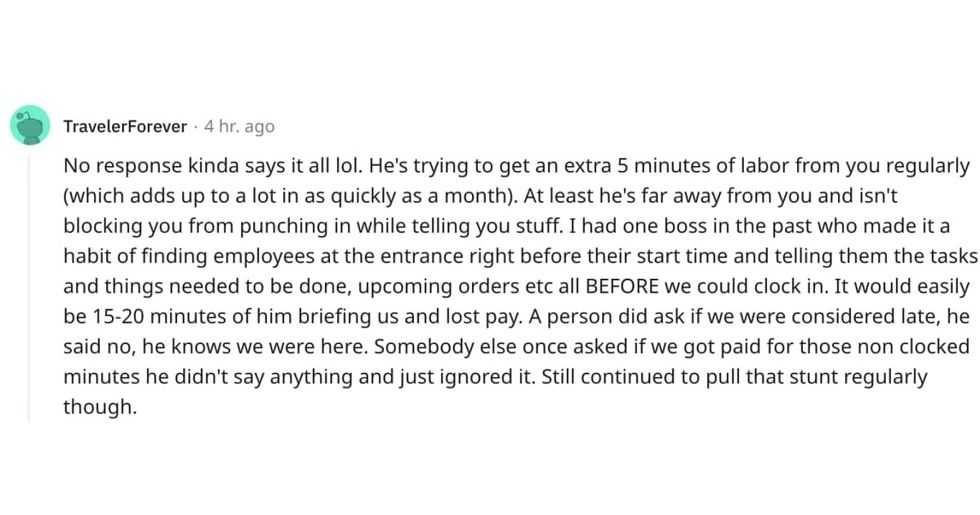

A Reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

A Reddit commentReddit |  Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via

A bartender makes a drinkCanva

A bartender makes a drinkCanva