Like most Egyptians, Nesyamun, an ancient Egyptian priest believed in the “afterlife.” When he was mummified nearly 3,000 years ago, his last wish was to continue his voice in the afterlife, as David Howard, a speech scientist at Royal Holloway, University of London told The New York Times. After three millennia, his wish finally came true, as some researchers from the U.K. reconstructed the mummy’s vocal tract using advanced 3D-printing technology. The findings are published in Scientific Reports.

During his lifetime, Nesyamun spent his days singing chants and performing rituals at the temple of Karnak in Thebes during the reign of Pharaoh Ramses XI. The mummy of Nesyamun, currently in the Leeds City Museum in England, was first uncovered in 1824. Several studies were carried out on his mummy, some of which revealed that he had died in his mid-50s with no damage to the bones around his neck. Synchronously, the inscription on his coffin read, “Nesyamun, true of voice.”

The researchers utilized a combination of CT scans, 3D printing, and an electronic larynx to carry out the study, per The Guardian. The project started in 2013 and involved many experts from fields like clinical science, archaeology, Egyptology, museum curation, and electrical engineering. "It has been such an interesting project that has opened a novel window onto the past and we're very excited to be able to share the sound with people for the first time in 3,000 years," Howard, who co-authored the study, said in a statement. Over the next six years, the team worked relentlessly to recreate the voice of the ancient priest. However, due to mummification and a prolonged time, the mummy’s tongue was shriveled and the soft palate was missing. So the researchers then coupled their system with an electronic larynx and loudspeaker.

Typically, the vocal tract filters the sound produced from air that has passed through the larynx, with the resulting sound unique to each person. The positioning of different components of the vocal tract results in the production of different sounds of words, vowels, and consonants. “Our larynx sound is electronic and if that sound were produced by Nesyamun, he would be passing lung air outwards via his larynx where his vocal folds would be vibrating to create the same effect,” Howard said.

Till now, the system can only produce a single sound, a vowel between “ah” and “eh.” Experts have likened the reconstructed sound to “a brief groan,” “a bit like a long, exasperated ‘meh’ without the ‘m,’” “a sound caught between the words ‘bed’ and ‘bad,’” “rather like ‘eeuuughhh,’” and “a sheep’s bleat.”

This is the first time that a technique has been used to resurrect the voice of a dead person. The sound, though, is not the actual voice of the priest, but a replica of what he would have sounded in the past. "Ultimately, this innovative interdisciplinary collaboration has given us the unique opportunity to hear the sound of someone long dead by virtue of their soft tissue preservation combined with new developments in technology," said co-author Professor Joann Fletcher. "While this has wide implications for both healthcare and museum display, its relevance conforms exactly to the ancient Egyptians' fundamental belief that 'to speak the name of the dead is to make them live again.'"

Added to this, Professor John Schofield, an archaeologist and co-author of the study, told The Guardian, “The idea of going to a museum and coming away having heard a voice from 3,000 years ago is the sort of thing people might well remember for a long time.”

Listen to the resurrected voice of the ancient priest here:

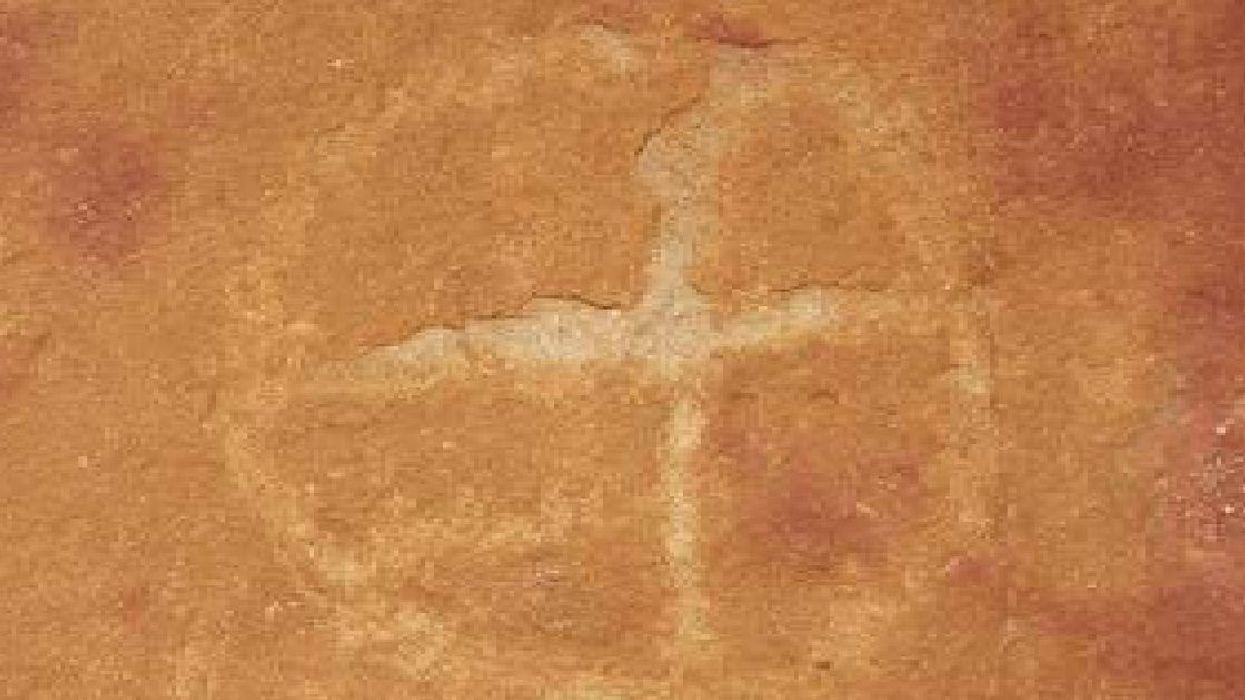

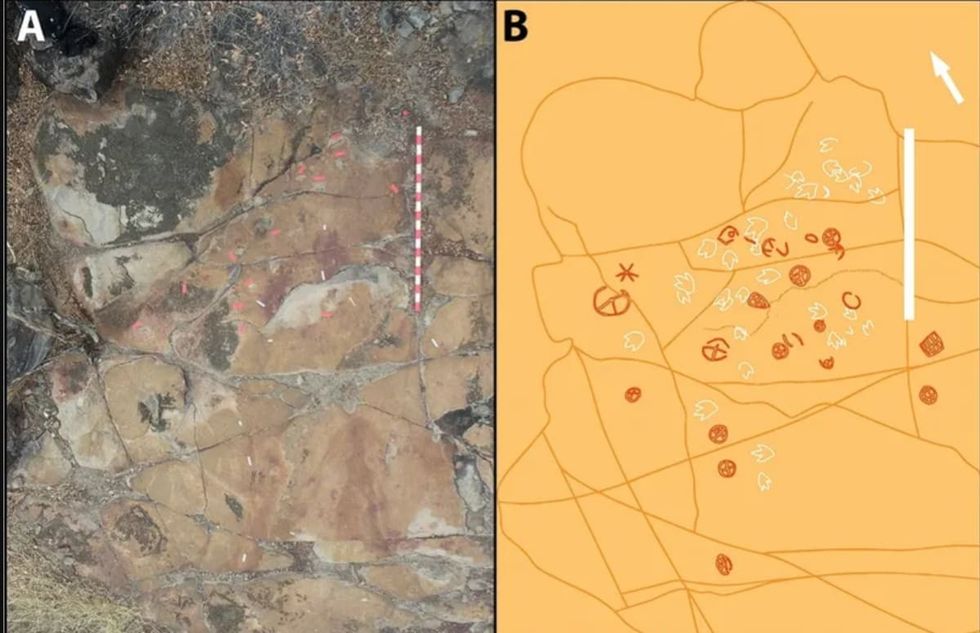

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:

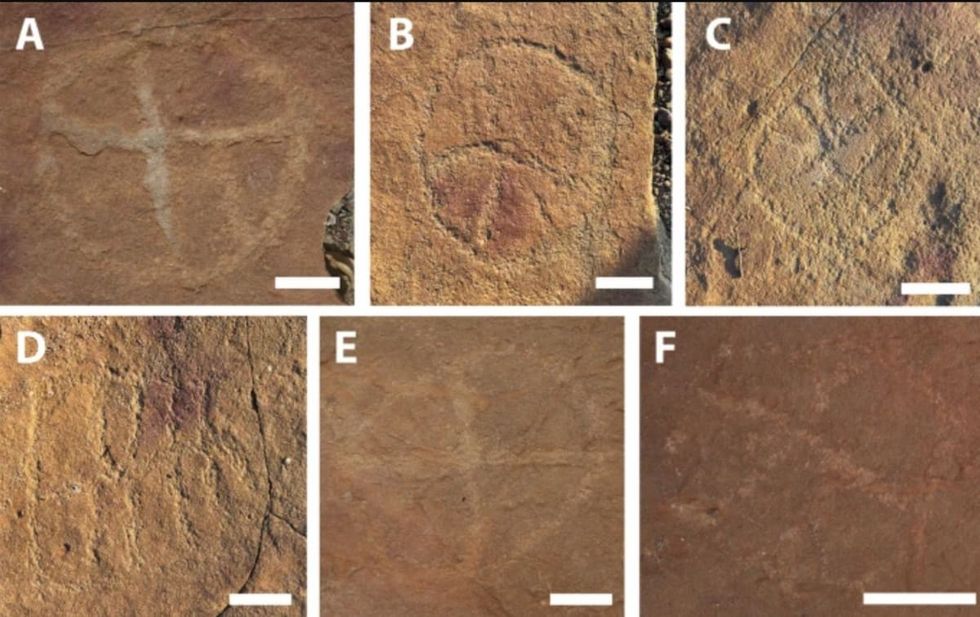

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

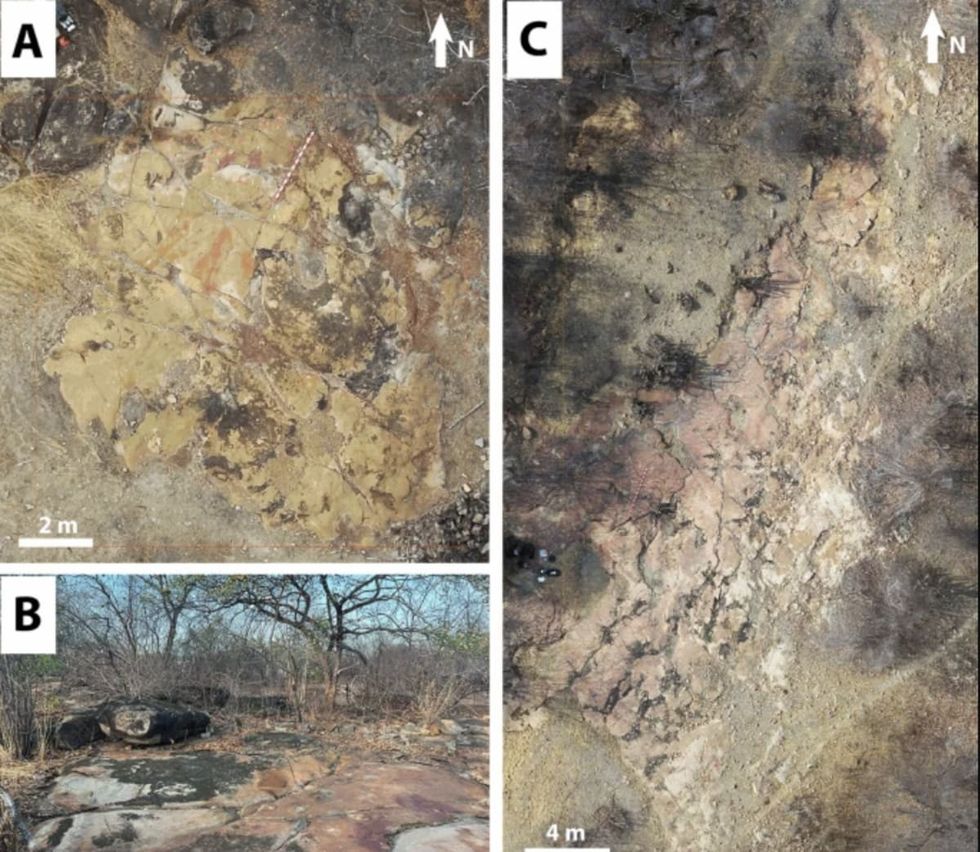

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

Sergei Krikalev in space.

Sergei Krikalev in space.

The team also crafted their canoe using ancient methods and Stone Age-style tools. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo

The team also crafted their canoe using ancient methods and Stone Age-style tools. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo The cedar dugout canoe crafted by the scientist team. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo

The cedar dugout canoe crafted by the scientist team. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo