To start, a feeder throws a fist-sized ball to a server, who kicks the ball over the net to the opposite end of the court. The point begins. Then members of three-person teams on each side can use their feet, knees, chest, and head to keep the ball in the air as they try to send it to the other side of the net. Points typically end with thunderous bicycle kicks that would make Lionel Messi jealous.

This is sepak takraw.

A sport native to southeast Asia, sepak takraw holds its most historic international tournament, the King’s Cup Sepaktakraw World Championship, this week in Bangkok. The International Sepaktakraw Federation (ISTAF) sanctioned competition launched in 1985 and has been held in Thailand since its debut, which annoys Malaysia, where the sport allegedly dates back the furthest. “Sepak takraw” is a combination of the Malay word for kick and the Thai word for woven ball.

Sepak takraw, fairly described as volleyball for ninjas, isn’t the only game of its kind, however. The world of kicking objects over nets for sport is vast and full of backflips.

Indigenous tribes in the Philippines invented sipa, which involves players acrobatically kicking a soft ball made of straw fragments. In fifth century B.C., China developed jianzi, played with a heavily weighted shuttlecock (Europeans alternately call the sport featherball, plumfoot, Federfußball, or simply shuttlecock). Kicking shuttlecocks also is Vietnam’s national sport, where it’s known as đá cầu.

More recently, soccer players in Prague created futnet (Slovakia calls it nohejbal) in 1922, originally played with a soccer ball and a low-hanging rope. Footvolley, invented on the beaches of Rio de Janeiro, is similar but is played on sand. There’s also jokgu, native to South Korea; footbag net, an American offspring of footbag (commonly known as Hacky Sack); and the imaginative bossaball, which is played on an inflatable court featuring two trampolines and is set to bossa nova music.

But sepak takraw perhaps is the most exciting. It’s played in a tight area about the size of a badminton doubles court, with a holed, fist-sized ball called a rattan, made of woven straw and sometimes covered in rubber.

Thailand dominates all five King’s Cup events (team, regu, double, hoop, and an experimental four-on-four division), partly due to the home-court advantage, but this year’s installment still drew 30 countries from Asia, North America, South America, and Europe.

And while contemporary iterations of the game favor the competitive aspect, at its best, sepak takraw skews closer to dance or martial arts with its graceful cooperative violence.

Though the sport’s popularity may be declining in its native Malaysia, it’s growing globally, aided by the ISTAF’s launch in 2011 of a World Cup and touring SuperSeries. The international availability of jaw-dropping YouTube highlights doesn’t hurt. But the holy grail of modern sport recognition, an Olympic bid, still evades sepak takraw.

“The Winter or Summer Games, I don’t mind,” ISTAF secretary general Abdul Halim Kader told BBC last year. “We would gladly take part in either.”

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |  Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva A female artist in her studioCanva

A female artist in her studioCanva A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva

A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva  A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva

A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva  A woman flexes her bicepCanva

A woman flexes her bicepCanva  A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva

A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva  Two women console each otherCanva

Two women console each otherCanva  Two women talking to each otherCanva

Two women talking to each otherCanva  Two people having a lively conversationCanva

Two people having a lively conversationCanva  Two women embrace in a hugCanva

Two women embrace in a hugCanva

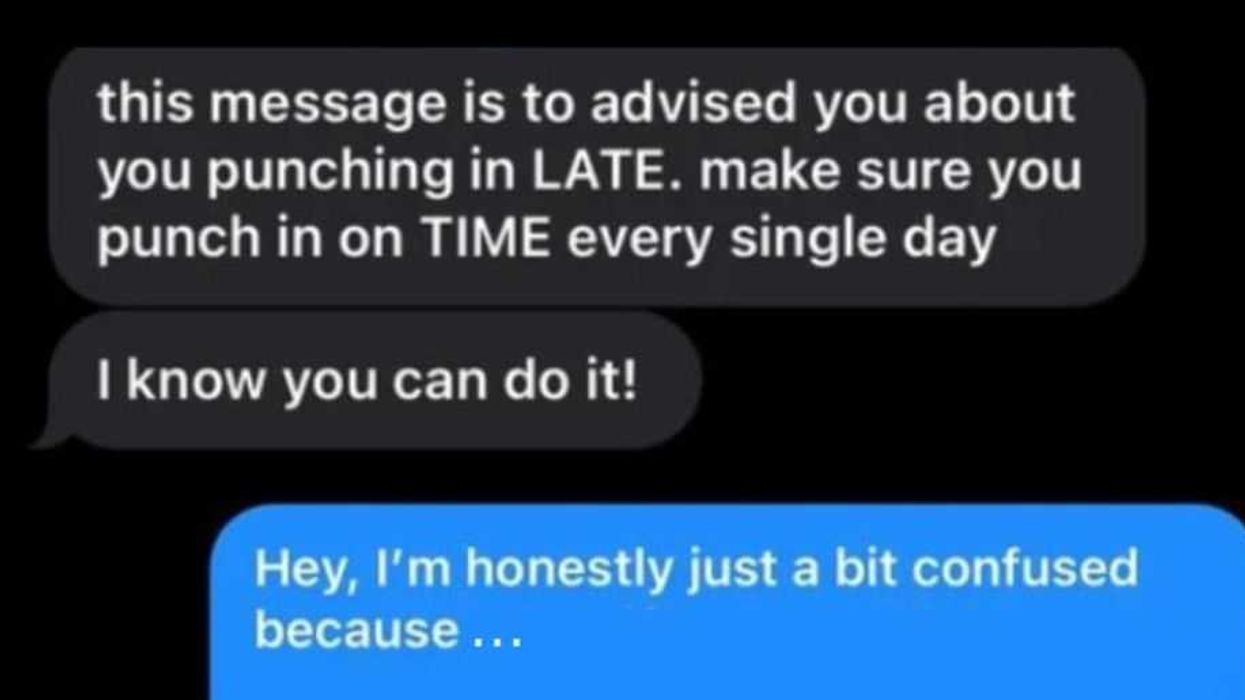

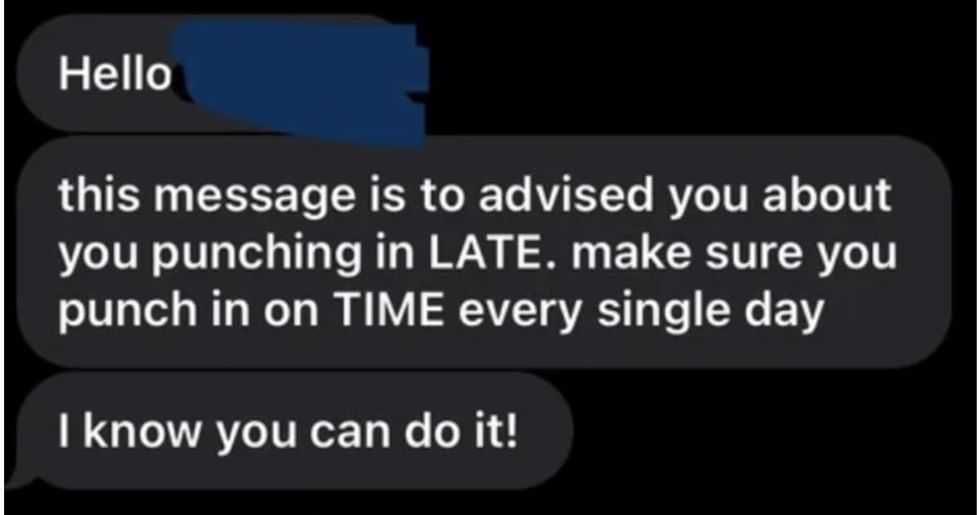

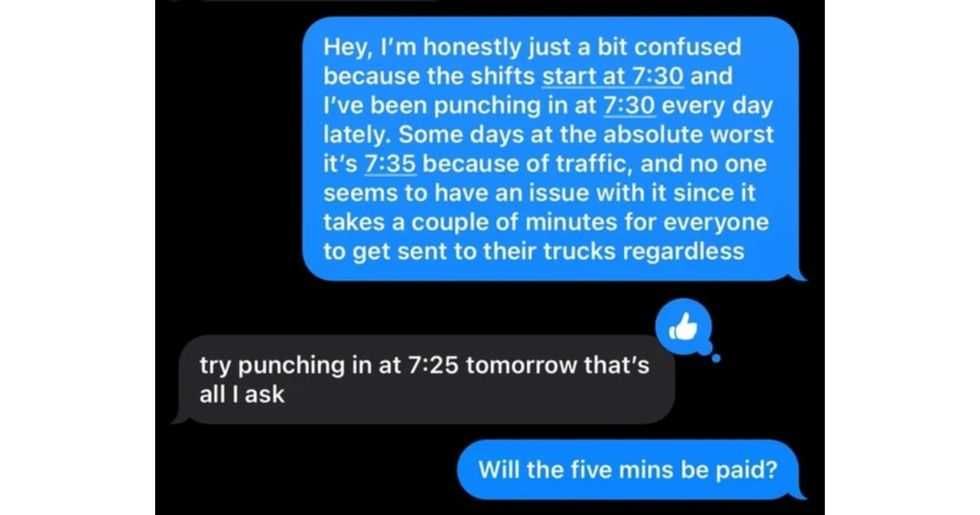

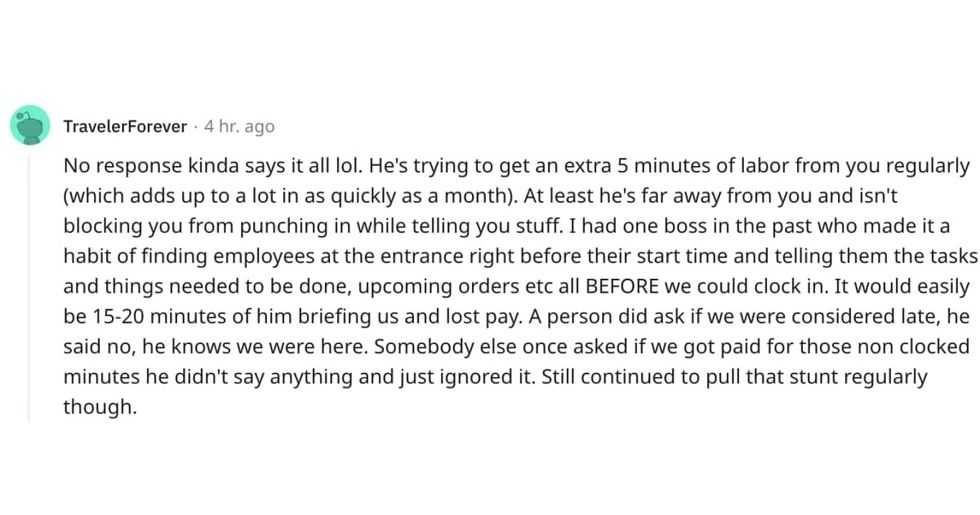

A reddit commentReddit |

A reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

A Reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

A Reddit commentReddit |  Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via

A bartender makes a drinkCanva

A bartender makes a drinkCanva