Over 300 years ago, when London’s streets were starting to ramble wildly with almost 600,000 people, a 27-year-old loner walked amid the crowd. Ben Browne had just moved to the city from a small English county village Westmorland in 1719. Here, his father had referred him to a job as a law clerk. Starting from day one, every day, he penned a letter to his family, primarily his father back in the village. He wrote about his financial worries, his social life, and just about everything he experienced in the bustling new city. In March 2024, a collection of these antique letters was restored and reported by the National Trust. They titled it “Letters from London.” The contents of these epistles depict how the fundamental life of a 20-something person was just the same in the 18th century as it is presently.

“These letters are so relatable, and they show nothing has really changed,” said Emma Wright, collections manager at Townend, according to the National Trust. The archive includes 65 letters that Browne mailed to his father. Currently on display at Townend, the historic Browne family home in Cumbria, England, “Letters From London,” illuminates some insights on what life would be like for a young person in their twenties living in London at this time. Some of these letters offer crisp details about Browne’s social life, nightlife, city’s highlights, but most of all, “expenses.”

In his handwritten letters, Browne often wrote to his father asking for money. “Mainly: Please send money, everything is so expensive,” read one of his letters, per The Guardian. He mentioned that he needed money to pay rent, and to purchase stockings, breeches, wigs, and other essential items. “Cloaths which [I] have now are but mean in Comparison [with] what they wear here,” he wrote.

Apart from communicating his financial concerns, Browne often complained about his long working hours. He elaborated that his employer, lawyer Richard Rowlandson made him work 12 hours straight from 8 am to 8 pm. He further expressed his frustration towards his father wondering why he had sent him on this job on a training contract of five long years. “I have lost the prime of my youth,” he lamented in a note.

![Representative Image Source: 'Still Life', 19th century (1935). From The Studio Volume 109. [The Offices of the Studio, London, 1935]Artist: Unknown. (Photo by The Print Collector/Getty Images)](https://www.good.is/media-library/representative-image-source-still-life-19th-century-1935-from-the-studio-volume-109-the-offices-of-the-studio-london.jpg?id=55299598&width=980)

However, by no means did his insufficiency for money stop him from living to the fullest. Browne had an active social life. He regularly hung out with his friends, ate and drank around Fleet Street, and toured through the city lights. National Trust likened the descriptions in Browne’s letters to the poetic works of William Hogarth, the satirical artist who depicted London’s “bawdy, boozy side.”

Sometimes, his family, friends, and neighbors sent him requests asking for things that were not available in the village but available in the city. He sent things like snuff boxes, a wig trunk, sealing wax, a silver thimble, caps & necklaces, and “Chocolate & Coffee for his mother.” In one letter, Browne announced that he had married Mary Branch, his employer’s maid, after having a discreet romantic relationship with her. He expected angst and disapproval from his father, but another letter revealed that his father had accepted his marriage to Mary. In a follow-up letter, he said his parents were so “affectionate.”

Browne also wrote about a “very great mobbing by the weavers of this town” who were “starved for want of trade.” He was, most probably, referring to the “Spitalfields riots” that occurred in London at this time. Spitalfields was the center of the silk-weaving industry since the 17th century. In 1719, agitation erupted among silkweavers related to imports of calico, dyed and patterned cloth from India, which had become very fashionable. This led to a decreasing demand for silk, and hence the revolution broke out.

Another interesting highlight unfolded from these letters was that Browne had a penchant for books. Townend officials discovered volumes of romances and Shakespearean plays in his belongings. Yet, oddly enough, he never mentioned books to his father in the letters. Besides, what’s surprising is, how he was able to afford these tomes given his financial condition was on the edge.

After hundreds of years, book conservator Ann-Marie Miller repaired the texts before they went on display in March 2024. “It has been a pleasure to tread the same steps as George Browne, as I have charted, and then reconstructed, his work as a bookbinder,” said Miller, per National Trust. “He took a great deal of care to preserve the correspondence between father and son, and I have tried to honor his intentions. I feel as if I have also got to know young Ben, with his solicitous turn of phrase and the flourish of his handwriting.” The letters are available to be seen till November 1.

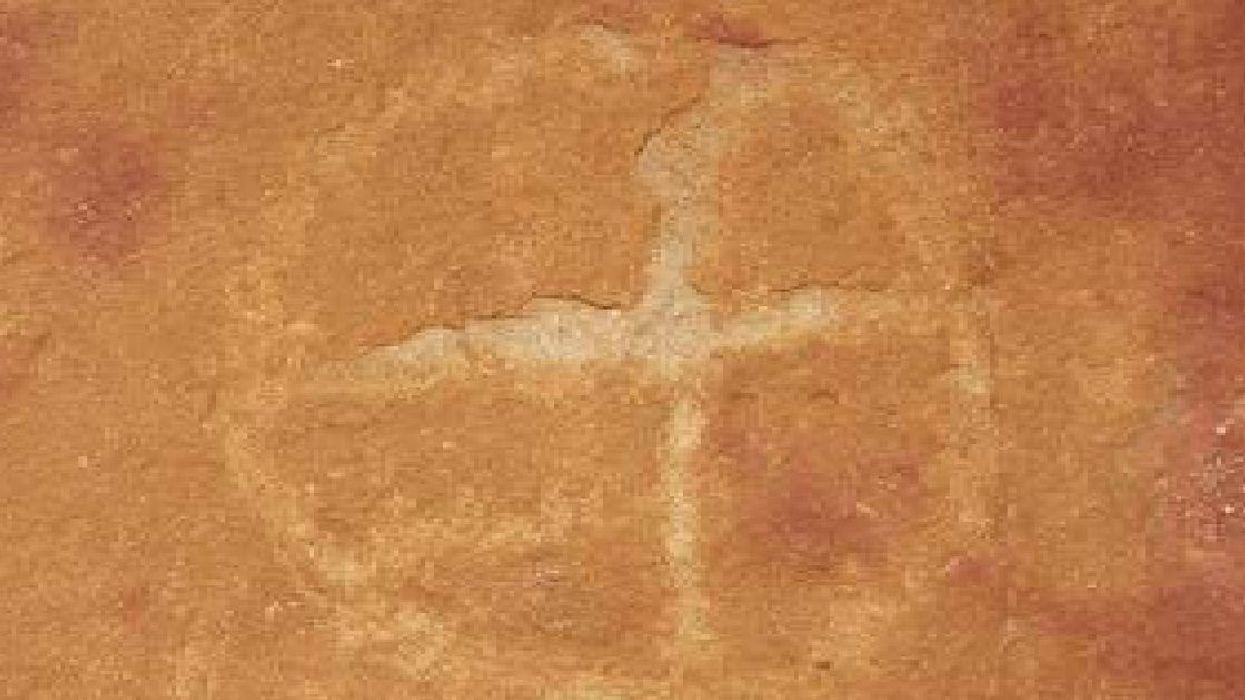

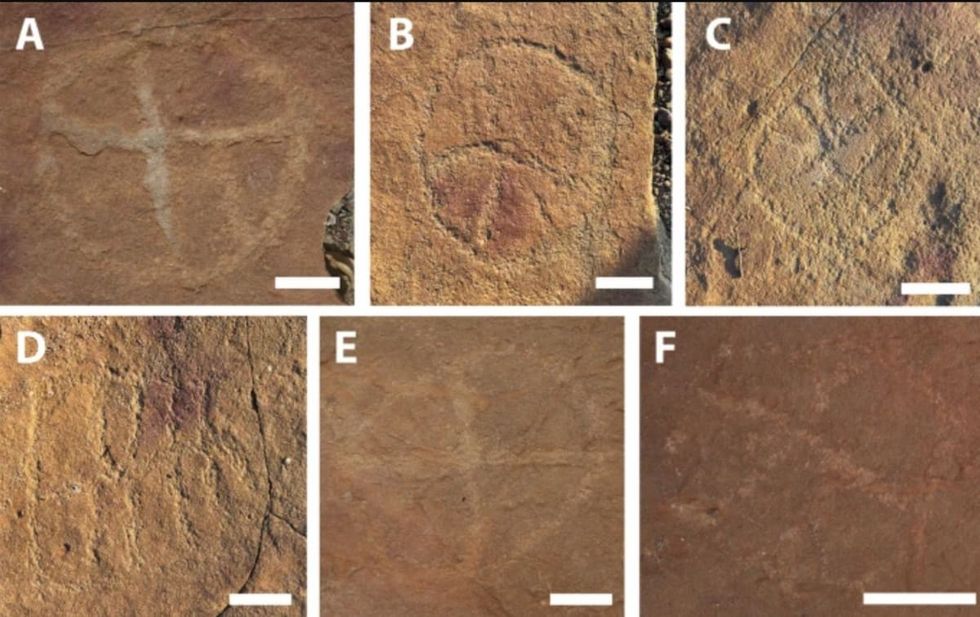

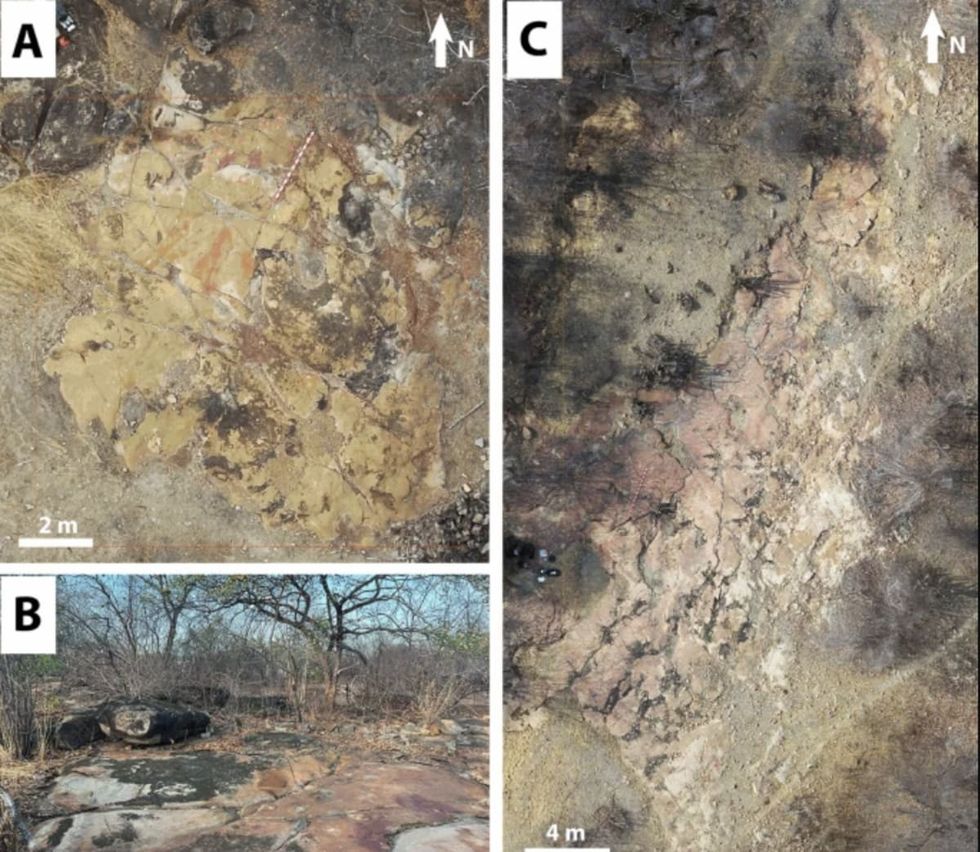

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

Sergei Krikalev in space.

Sergei Krikalev in space.

The team also crafted their canoe using ancient methods and Stone Age-style tools. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo

The team also crafted their canoe using ancient methods and Stone Age-style tools. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo The cedar dugout canoe crafted by the scientist team. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo

The cedar dugout canoe crafted by the scientist team. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo