From eight glasses of water a day to protein shakes, we’re bombarded with messages about we should drink and when, especially during exercise. But these drinking dogmas are relatively new. For example, in the 1970s, marathon runners were discouraged from drinking fluids for fear that it would slow them down.

Now we’re obsessed with staying hydrated when we exercise, not just with water but with specialist drinks that claim to do a better job of preventing dehydration and even improve athletic performance. Yet the evidence for these drinks’ benefits is actually quite limited. They might even be bad for your health in some instances. So how did sports drinks come to be seen as so important?

Much of the focus on hydration can be traced back to the boom in road running, which began with the New York marathon in the 70s. Sports and drinks manufacturers spotted a growing market and launched specialist products for would-be athletes. The first experimental batch of Gatorade sports drink cost £28 to produce but has spawned an industry with sales of around £260m a year in the UK alone. And consumption is increasing steadily, making it the fastest-growing sector in the UK soft drinks market in recent years. What started life as a mixture of simple kitchen food stuffs has become an “essential piece of sporting equipment”.

Marketing victory

The key behind this huge rise in sports drinks lies in the coupling of science with creative marketing. An investigation by the British Medical Journal has found that drinks companies started sponsoring scientists to carry out research on hydration, which spawned a whole new area of science. These same scientists advise influential sports medicine organisations, developing guidelines that have filtered down to health advice from bodies such as the European Food Safety Authority and the International Olympic Committee. Such advice has helped spread fear about the dangers of dehydration.

One of industry’s greatest successes was to pass off the idea that the body’s natural thirst system is not a perfect mechanism for detecting and responding to dehydration. These include claims that: “The human thirst mechanism is an inaccurate short-term indicator of fluid needs … Unfortunately, there is no clear physiological signal that dehydration is occurring.”

As a result, healthcare organisations routinely give advice to ignore your natural thirst mechanism. Diabetes UK, for example, advises: “Drink small amounts frequently, even if you are not thirsty -— approximately 150 ml of fluid every 15 minutes -— because dehydration dramatically affects performance.”

Drinks manufacturers claim that the sodium in sports drinks make you feel thirstier, encouraging you to consume a higher volume of liquid compared with drinking water. They also claim these drinks enable you to retain more liquid once you’ve consumed it, based on the observation that the carbohydrates found in the drinks aid water absorption from the small intestine.

This implies that your thirst mechanism needs enhancing to encourage you to drink enough. But research actually shows natural thirst is a more reliable trigger. A review of research on time trial cyclists concluded that relying on thirst to gauge the need for fluid replacement was the best strategy. This “meta-analysis” showed for the first time that drinking according to how thirsty you are will maximise your endurance performance.

On top of this, many of the claims about sports drinks are often repeated without reference to any evidence. A British Medical Journal review screened 1,035 web pages on sports drinks and identified 431 claims they enhanced athletic performance for a total of 104 different products. More than half the sites did not provide any references – and of the references that were given, they were unable to systematically identify strengths and weaknesses. Of the remaining half, 84 percent referred to studies judged to be at high risk of bias, only three were judged high quality and none referred to systematic reviews, which give the strongest form of evidence.

More harm than good?

One of the key problems with many of the studies into the benefits of sports drinks is that they recruit highly trained volunteers who sustain exercise at high intensity for long periods. But the vast majority of sports drink users train for very few hours per week or exercise at a relatively low intensity (for example walking instead of running during a race). This means the current evidence is not of sufficient quality to inform the public about benefits deriving from sport drinks.

Even more importantly, as sports drinks rise in popularity among children, they may be contributing to obesity levels. A 500ml bottle of a sports drink typically contains around 20g of sugar (about five teapsoons’ worth) and so represents a large amount of calories entering the body. But endorsements by elite athletes and claims of hydration benefits have meant sports drinks have shrugged off unhealthy associations in many people’s eyes. One study found more than a quarter of American parents believe that sports drinks are healthy for children.

That’s not to say hydration research into different drinks isn’t useful. For example, it could help identify which drinks help the body retain fluids in the longer term. This would be of real benefit in situations where athletes have limited access to fluids or can’t take frequent toilet breaks.

But the current evidence is not good enough to inform the public about the benefits and harms of sports products. What we can be almost sure about is that sports drink are not helping turn casual runners into Olympic athletes. In fact, if they avoided these sugar-laden drinks they would be probably be slimmer and so faster.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

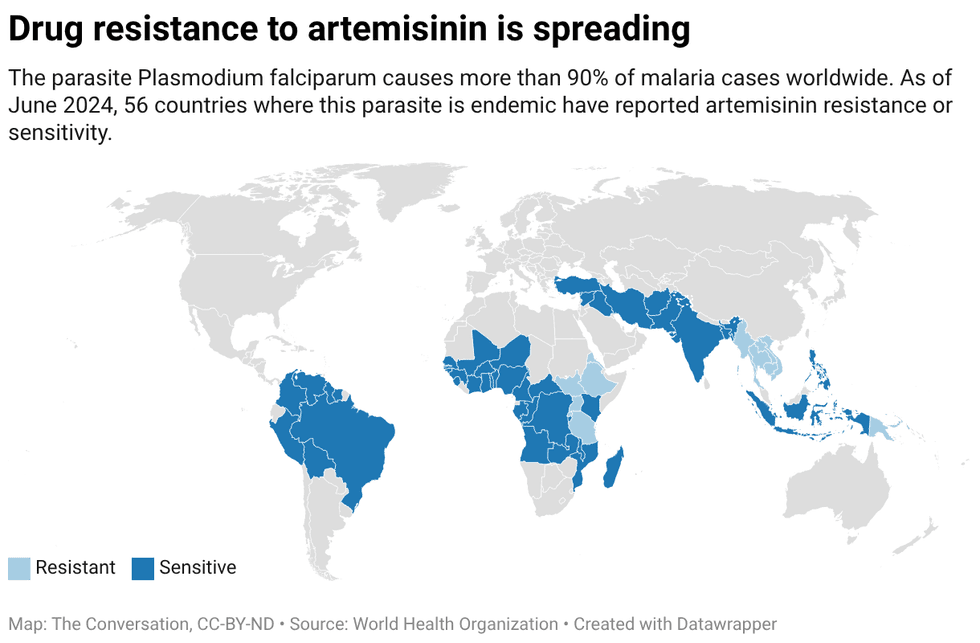

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

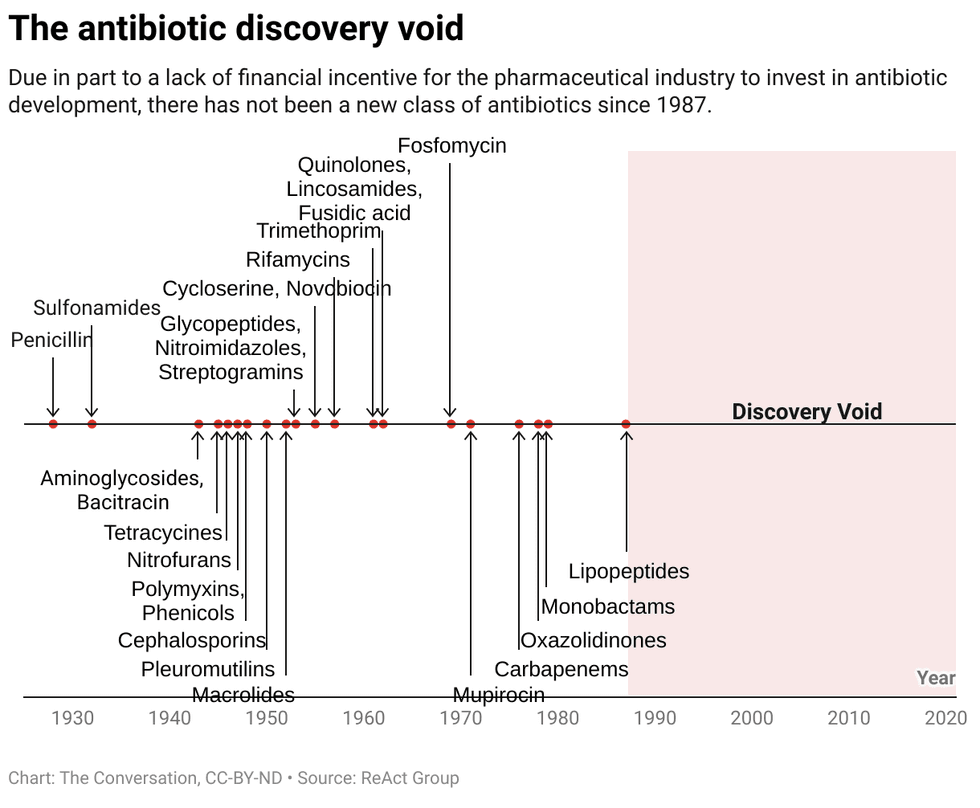

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.