Imagine you’re three months into a new job. You’ve just skipped lunch, even though your only sustenance since starting work last night was the graham crackers you pilfered from the supply closet. You have a pounding migraine from dehydration.

And you’re confronted with a life and death situation where the decisions are in your hands.

This is a typical day for a medical resident. It’s an intense experience that many seek out, but at what sacrifice to their health—and ours?

Consider some recent research on physician wellness. Not only are physicians at higher risk for burnout, depression, and substance abuse, but your doctor is six times more likely to commit suicide than you are. Add the fact that doctors who are overworked are more likely to make mistakes in patient care, and the importance of doctor care should be clear. We need our doctors to be healthy, for their sake and ours.

When Vinitha Watson, design strategist and philanthropist supporting the resident wellness program at Johns Hopkins Hospital, approached our creative team at Daylight to do something about this, we were thrilled. Daylight’s mantra is “inspired by people, designed for impact,” so spending meaningful time with residents to understand their lives was critical. Our ethnography team hurried along with the flock of white-coated residents as they raced through the hospital during crack-of-dawn patient rounds. We listened to the stories and challenges of residents, faculty, and administrators. And we stayed late into the nights to understand what really happens at 3 a.m. in the hospital.

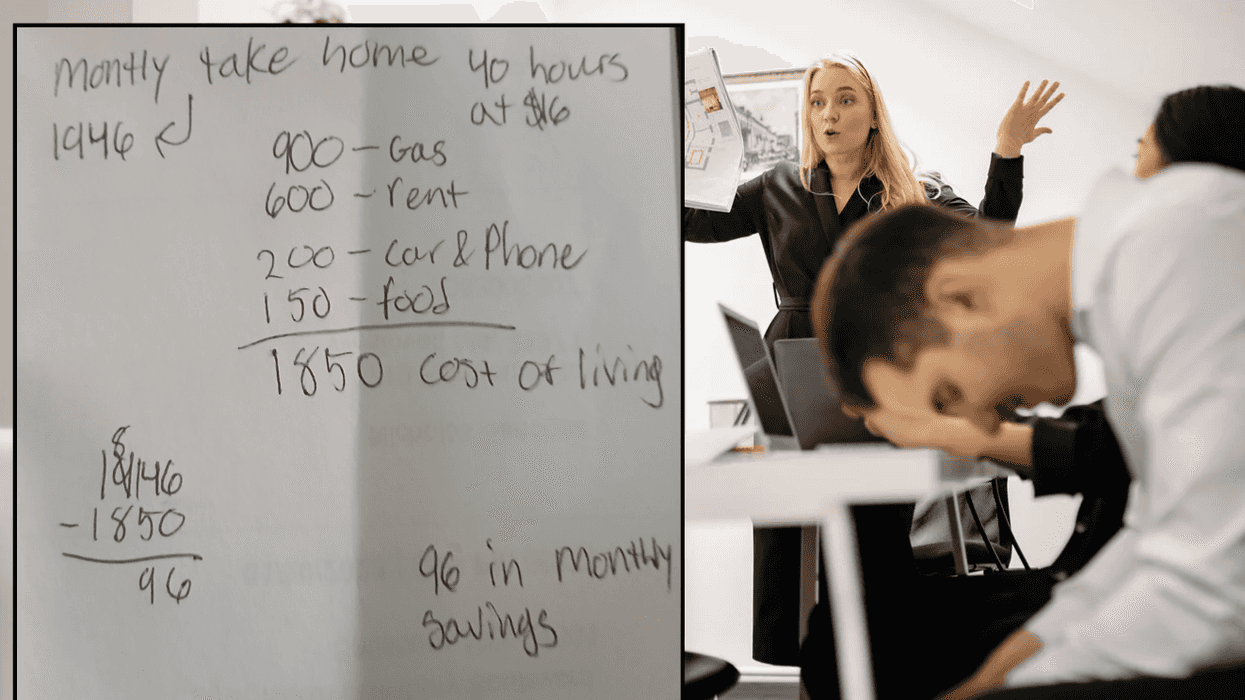

We walked away from our immersive experiences with a surprising discovery—Maslow’s pyramid of needs was oddly inverted for these residents. While most had a profound sense of meaning in their lives, it was their bottom-of-the-pyramid needs—healthy food, staying hydrated, having time to do little life errands—that went unaddressed.

But here was the challenge. These residents wanted to be pushed to their limit because they believed it was helping them pursue their calling. They know health is important, but not if it takes away from the intense learning experience they signed up for. Taking a two-hour yoga lunch break? Not going to happen. Wellness would only work if these residents believed the solutions we generated wouldn’t get in the way of their intense efforts to become the excellent physicians they wish to be.

So that’s exactly what we set out to do. If residents couldn’t find time to make it to the cafeteria, we’d bring the cafeteria to them—stocking the resident-only workspaces with healthy, high-energy food they could just grab and take. Plumbing that workspace with a water line and giving every resident a water bottle to make staying hydrated a little easier was another no-brainer.

Other proposed interventions focus on helping residents with little life chores, letting them spend more of their precious downtime connecting with family or simply just getting a little more sleep. In-hospital dry cleaning and package delivery, dental and physical appointments that fit into residents’ crazy schedules, and vouchers for a house-cleaning service are all experiments we are exploring.

As these basic needs get addressed, we can move on to some of our other interventions focusing on emotional support. But for now, we simply hope to help these idealistic doctors better attend to their basic needs, so they can better attend to those of others. And we hope what we learn at Johns Hopkins can contribute to an informed conversation about the importance of physician wellness and the ways designing small changes can add up to meaningful social impact.

Image via Daylight Design

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.