There is a commonly held belief in both the economics and finance literature that men tend to be more “risk-loving” and women tend to be more “risk-averse.” In economics, the same line of logic extends to differences in gendered attitudes towards career risk and bargaining over compensation. It’s been proven that men gamble more than women; men are also better at negotiating for higher wages. They seem willing to bet more often, take on higher stakes, and ask for more (which can be seen as risky in and of itself), leading to bigger gains.

But what about emotional matters? Do men also engage in risky behavior in their personal relationships? In our modern culture, romantic comedy movies are geared toward women and marriage is glorified for women through the wedding industrial complex with shows like “Say Yes To The Dress.” Does this lead to a paradigm where women are perhaps riskier in their believe in love? And, in turn, what economic consequences would this have for women?

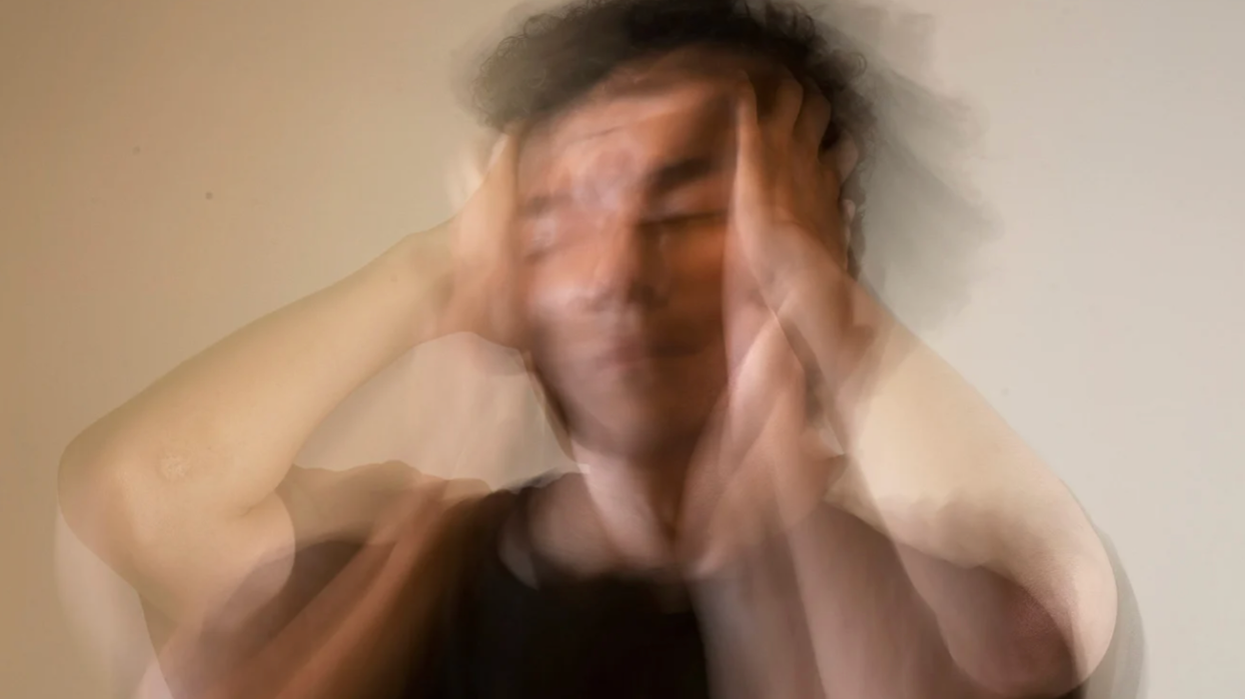

I tend to be very risk-averse, or so I thought. The most I’ve ever gambled was $3 on a horse race. I spent the entirety of my 20s with one partner and most of that time I was also in graduate school getting my PhD in economics. Both seemed like safe investments. I trusted that my relationship was stable and I was getting a degree that would increase my earning potential. But after an unexpected divorce a year ago, I’ve reflected—both as an economist and a woman—on the actual conditions of risk that that women face in love and in the economy, and how my perceptions of those risks might have impacted my life.

Men are riskier in financial matters, but they are also more privileged in the economy, rewarded with higher wages and more frequent promotions. Like the majority of opposite-sex couples, the man in my relationship was the higher earning partner. While I will probably do alright professionally with a degree in a well-respected field, my ex out-earned me by a large margin and this, frankly, made me overly-financially dependent. I even wrote a piece for The Guardian explaining my discomfort with the situation and how it conflicted with my ideals as a feminist. By function of his greater earning power, our relationship too, became less of a gamble, a proposition in which he had less to lose.

When we broke up, I found myself in a precarious, typically female financial situation—I wasn’t prepared to independently support myself. Settling down with the person I met as a teenager turned out to be a risky move that led me to question whether falling in love is a particularly bad bet for women.

Love is risky, and I argue that it’s even riskier for women compared to men. Women are more likely to be the lower earning partner in a relationship, like I was, increasing the chances of financial dependency. And when men prefer dating younger women, women have greater risks associated with the dissolution of a relationship once they are past their supposedly desirable age.

My situation, of being left in a vulnerable position after divorce, is not unusual as a woman. Divorce tends to leave women worse off and men better off. One estimate is that women are 27 percent financially worse off after divorce and men are 10 percent better off. So why do we live in a culture where women are encouraged to be risky in love when it has negative consequences, and relatively little discussion on the importance of maintaining financial independence even when married?

The answer probably lies in the continued power of traditional gender structures. Research on gender and risk are rarely related to gender theory. Gender socialization and the culture of gender often reinforce a system where men have more social and economic power. I’m not saying it is a conspiracy where rom-coms are made in order to make women economically dependent on men, but the complex social, economic, and political world results in these conditions and they are very hard to undo.

Rom coms are based on the conflict within a partnership that shouldn’t work, but for some reason—love?—does. Just think about the modern classic Knocked Up, where an ambitious and beautiful woman ends up pregnant by an unmotivated stoner and then settles down with him once he cleans his act up. Does this actually happen? If men are more risk-loving, shouldn’t they be taking more chances on us? This would mean more men would marry older women, where there could be more risks of a shorter timeline for having children, or more men would be simply willing to date challenging women who have ambitious careers and less time and energy for the domestic sphere.

I can’t swear off love, even if it’s risky both for my heart and my financial stability. But I also think that through a constructive feminist dialogue we can begin to at least think critically about how we are influenced by our gender in our romantic and economic lives, given the current structures of power and moving beyond them. I hope to find another partner some day, but I know that with what I know as an economist and as an adult woman will change how risky it will be for me, and hopefully make it less so, in the future.

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.