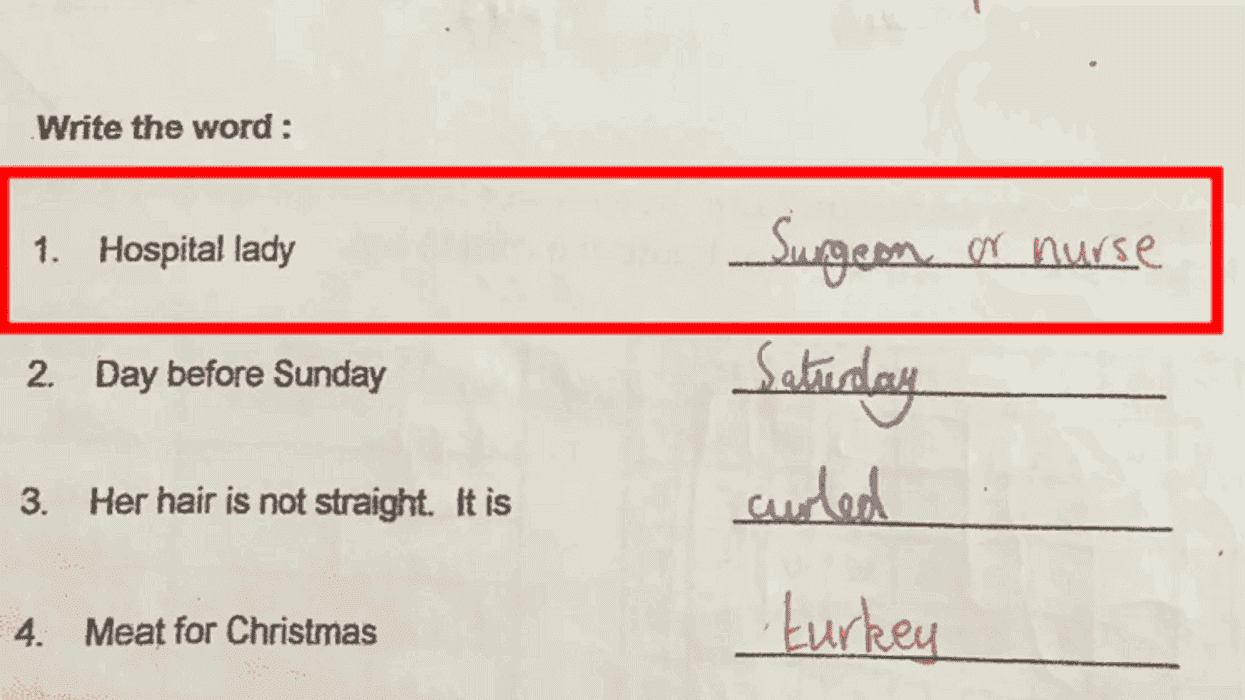

While at a protest at Los Angeles International Airport against President Trump’s Muslim ban, I watched as a white woman approached two Muslim women in headscarves. She carried with her Shepard Fairey’s now-inescapable American hijab poster—which depicts a Muslim woman wearing an American flag print headscarf—and plastered on her face was the kind of expectant smile I’d come to recognize from well-meaning, but misguided, white non-Muslims. I couldn’t hear what she was saying, but I already knew what she wanted: a photo with the Muslim women while holding the poster. They posed patiently, their smiles strained, for what would surely become her protest Instagram or Facebook photo.

I’ve seen this before. In fact, I’ve been subjected to similar behavior. As a college student and a rookie journalist, I was sent to the Occupy LA encampment at Los Angeles City Hall to report on the protests. I tried to be inconspicuous, but my headscarf marked me as an “other,” an exotic signifier of diversity. In a movement that had frequently been criticized for being overwhelmingly white, I was a welcome addition to the tableau of diversity they so desperately desired. People flocked over to tell me how happy they were to have me there. I had to clarify, over and over again, I was only there as an observer. Still, they took photos of me.

Go to any of the recent, large-scale protests happening across the country and you’ll likely see it for yourself—Muslim women in headscarves being pulled aside for photographs and selfies. Once, at a pride festival in Istanbul, my headscarved friend was stopped by an American tourist. “Can I take a picture?” she asked. “The people back in New York will love this.” Another friend from Brooklyn experiences this so often that whenever she attends demonstrations, she now carries a sign with her that reads: “Not Your Token Diversity Photo.”

Where do these images go once they are taken? Often they are packaged as what can be categorized as “protest porn.” Disseminated across media channels, they help build narratives about the causes they represent. Photos from the Women’s March depicted joyful crowds of women, united against a common enemy—Donald Trump, a useful avatar for “the patriarchy”—peacefully marching alongside and under the protection of police officers. It’s important to question why we don’t see the same happy-go-lucky images from Black Lives Matter protests. Instead, we see photos of police confronting black activists, reinforcing notions that Black Lives Matter is a controversial issue, one at odds with the state, championed by “violent” people.

On the other hand, images that depict Muslim women in positions of resistance carry a special political weight in the visual economy because they are often perceived as docile or subjugated. Consider why Shepard Fairey, a white male artist, frequently deploys images of Muslim women in his political graphic art? It’s because the Muslim woman—her body, and what goes on top of it—has been rendered into a political object. But while their likeness is abundant, their voices are usually absent. They weren’t at the Women’s March in LA, where Fairey’s poster was ubiquitous, nor were they at the airport. Those who monopolized the mic or the megaphone were often white or male.

Protest porn isn’t limited to photos of defiant Muslim women carrying signs at demonstrations. The rapid devaluation of protest into spectacle and pageantry can include photos of pet protestors, funny signs, and jubilant protest selfies. On my way to the LAX march, my Instagram feed was overwhelmed by these—I scrolled pass the smiling faces of my non-Muslim friends, posing against the human tide of the demonstration. When I got there, I witnessed much of the same: cheerful protesters, exhilarated by the large turnout and the collective camaraderie. A friend of mine, frustrated, began approaching protesters one by one to tell them to call their representatives when they went home.

Certainly, protests can be sources of inspiration. But the mood lately has felt too celebratory in advance of any real result, and the protesters seem to be too self-satisfied with their presence. I’m Muslim, and a Libyan-American dual citizen. My faith and ethnic background make me particularly vulnerable to the policies of the Trump administration. I could not share in their joy. The day the travel ban was announced—and every day since—has been one of mourning. And it was a struggle for me, to stand amongst so many non-Muslims and to feel that grief alone. There was no valve for my sadness, no mechanism for catharsis. I didn’t leave the protest feeling energized or mobilized; I felt malaise instead.

Don’t get me wrong. Protests serve a great function in progressive movements. Large protests can showcase wide-scale opposition to injustice and inject dissent and resistance into public narratives. There is a great power in the visibility of protests. When people turn on their TVs to watch the evening news, images of massive demonstrations can help awaken them to the urgency for action.

But protests should be only the first step in organizing. They should function also as a meeting place for like-minded folks. Beyond marching, protesters should be connecting with each other and arranging post-march meetings to arrange and act on next steps. The voices of marginalized folks should be prioritized, and they should be trusted to lead chants and direct the crowds—not utilized as diverse window dressing. Many of these folks have been protesting and organizing for decades; they’ve been actively developing strategies for resistance for a very long time. The Muslim-American community, for example, has worked to counteract other Islamophobic policies and legislation, like the Department of Homeland Security’s Countering Violent Extremism program, and the Bush-era National Security Entry-Exit Registration System, under which Trump’s “Muslim registry” plan would reactivate. Black Lives Matter has been building coalitions with other social justice movements and establishing more effective forms of protest that instigate real institutional change. Budding protestors would do well to take cues from them.

This is by no means an argument against protesting. Go out, march, demonstrate, and raise your signs. Our visibility in the streets—as resistors to encroaching fascism—is necessary to the growth of the movement. But the next time you raise your camera, think about who you’re aiming it at, and towards what aim.

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

A home pregnancy test Canva

A home pregnancy test Canva

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

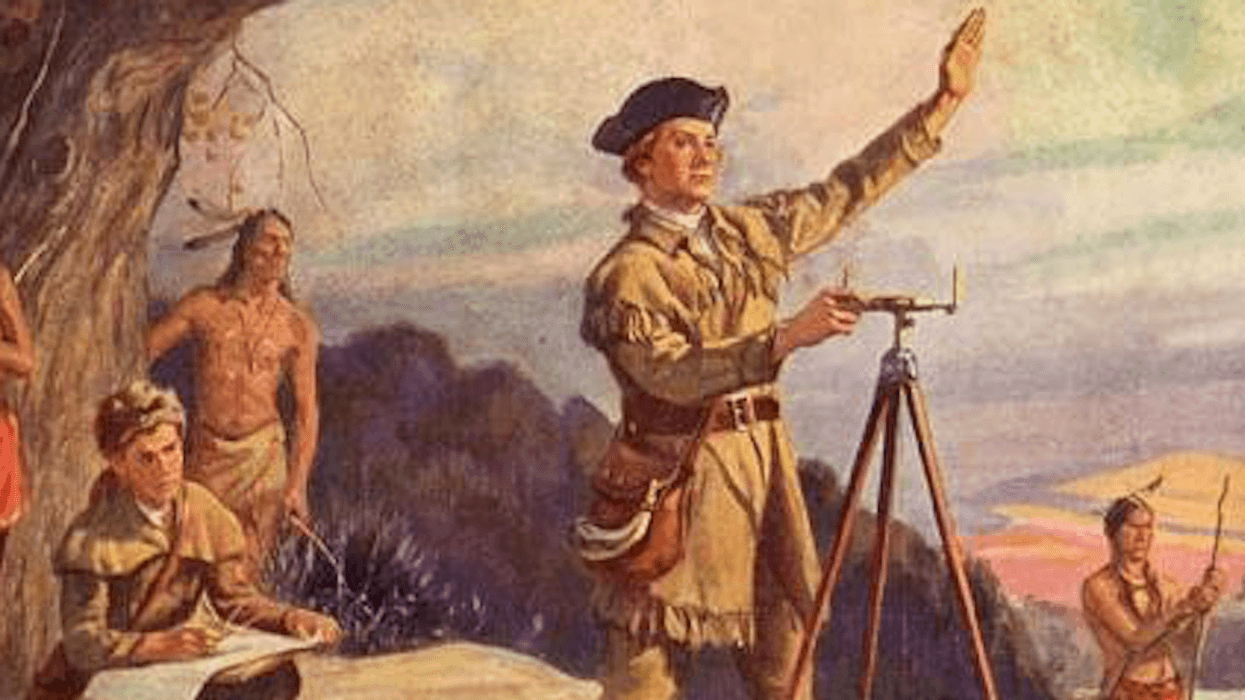

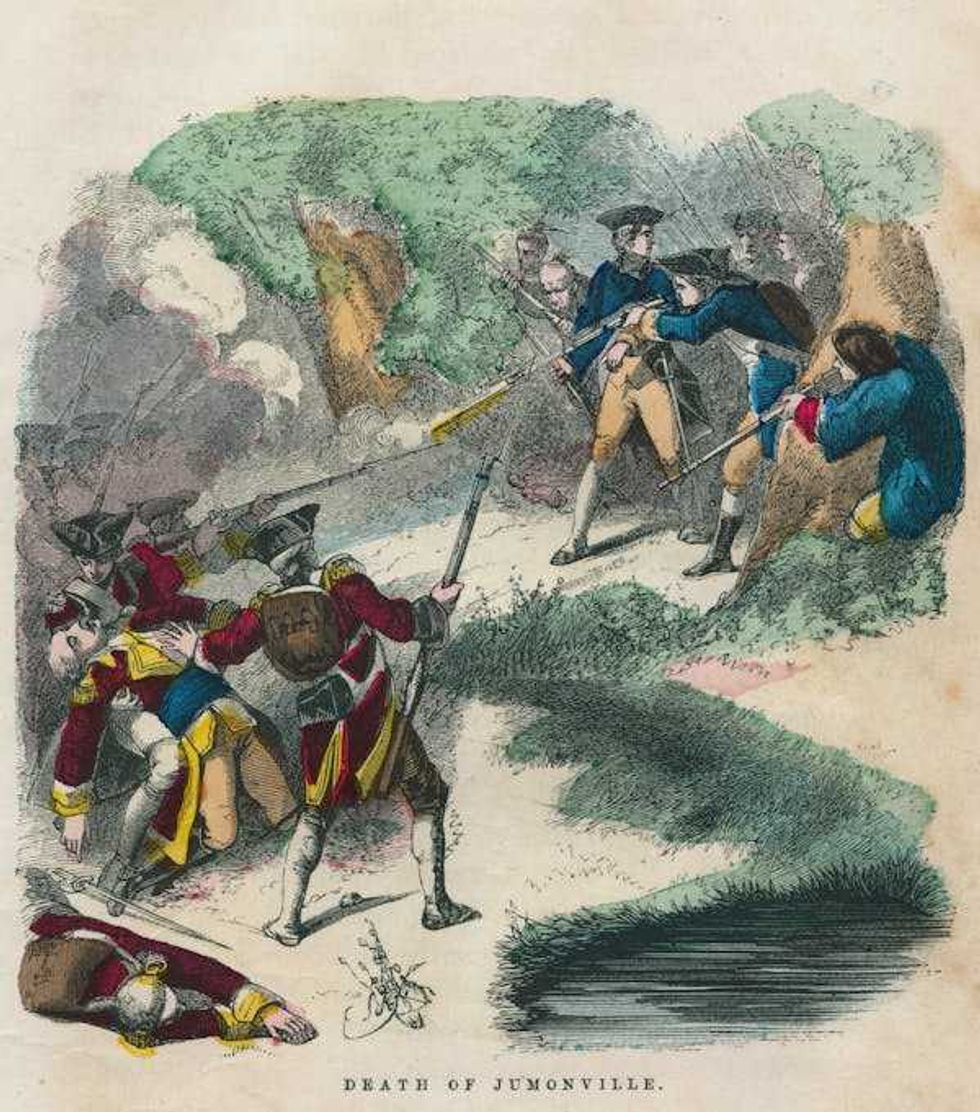

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War.

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War. Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity.

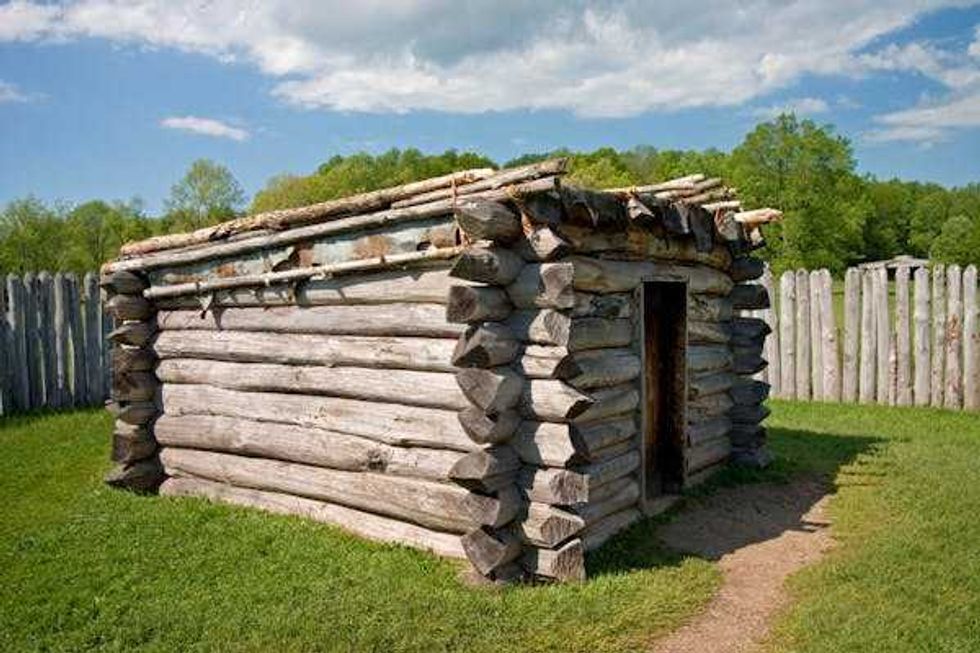

Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity. A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

A young woman scrolling on her phoneCanva

A young woman scrolling on her phoneCanva Gig of two cartoon penguins watching TV via

Gig of two cartoon penguins watching TV via  Gif of a storm trooper flipping through sings that say 'no' via

Gif of a storm trooper flipping through sings that say 'no' via