In the Academy Award-nominated film Lion, a five-year-old Indian boy named Saroo sees the sweet, sticky Indian dessert, jalebi, at a street market. Moments later, he gets lost, takes a train ride to Kolkata by chance, and eventually lands in an orphanage from where he is adopted by an Australian couple. Years later, Saroo, happens upon a plate of the funnel cake-like confectionery, which triggers memories of India and his first family. The food memory prompts Saroo to embark on a quest to find them.

It’s not surprising that encountering the treat triggers Saroo’s memory: jalebi is India’s most beloved sweets. But in fact, it isn’t even truly of South Asian origin. By most historical accounts, jalebi is of West Asian provenance and made its way to the subcontinent in the 14th or 15th century via trade. The oldest recipe for the precursor to jalebi, the zalabiya, an ancient pastry known by different names across Asia—zalabiya in Arabia, mushabbak in Levant, zulbia in Iran, and jalebi on both the Indian subcontinent and in Afghanistan—appears in a 10th-century Baghdadi cookbook, Kitab-al-Tabikh. The sweet was distributed to the poor during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan. “Its meaning has [since] drifted in several directions,” said food scholar Darra Goldstein in The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets.

But jalebi has found its most ardent devotees in South Asia, where it’s a wildly popular street food often served on holidays and celebrations. Generally, a jalebi is made by extruding a thin batter of flour or lentils into hot oil to form large spirals that are later soaked in warm sugar syrup. The jalebi most familiar to Western food lovers, and as seen in Lion, are made of maida flour—a finely milled wheat flour—and Bengal gram flour—a flour milled from chickpeas—drenched in a syrup usually flavored with cardamom and saffron. Other ingredients may include lime juice or sour yogurt for tang, or rose water for a floral note. One regional variation, called cheeni mittai, is “made using rice flour, urad dal [split black gram] and powdered cardamom... deep-fried in swirl shapes, and soaked in three kinds of sugar syrups (cane sugar, cane jaggery and palm sugar), one after the other,” said Awanthi Vardaraj in Paste magazine. Another variety, imartee, is also made with urad dal instead of flour, but is spun into geometric swirls around a center instead of into a lattice.

A perfect jalebi is a mish-mash of textures—crispy on the outside and chewy on the inside—and oozes sticky syrup with every bite. It’s mesmerizing to watch a jalebi-wallah (jalebi maker) swirl and whirl smooth batter into the hot oil, deftly flipping the dessert over until it has cooked through. My recommendation? Garam-garam (hot-hot) jalebi straight from the fryer, soaked for a minute or two in sugar syrup—although some prefer cold jalebi, often set to dry for several hours until the syrup has formed a hard shell.

But that’s part of the beauty of jalebi—it is delicious in all forms, which perhaps explains Saroo’s reaction when tasting the dessert after so many years, and so many thousands of miles away from his original introduction. It tasted like home.

A woman relaxes with a book at homeCanva

A woman relaxes with a book at homeCanva An eviction notice is being attached to a doorCanva

An eviction notice is being attached to a doorCanva Gif of Kristen Bell saying 'Ya basic!' via

Gif of Kristen Bell saying 'Ya basic!' via

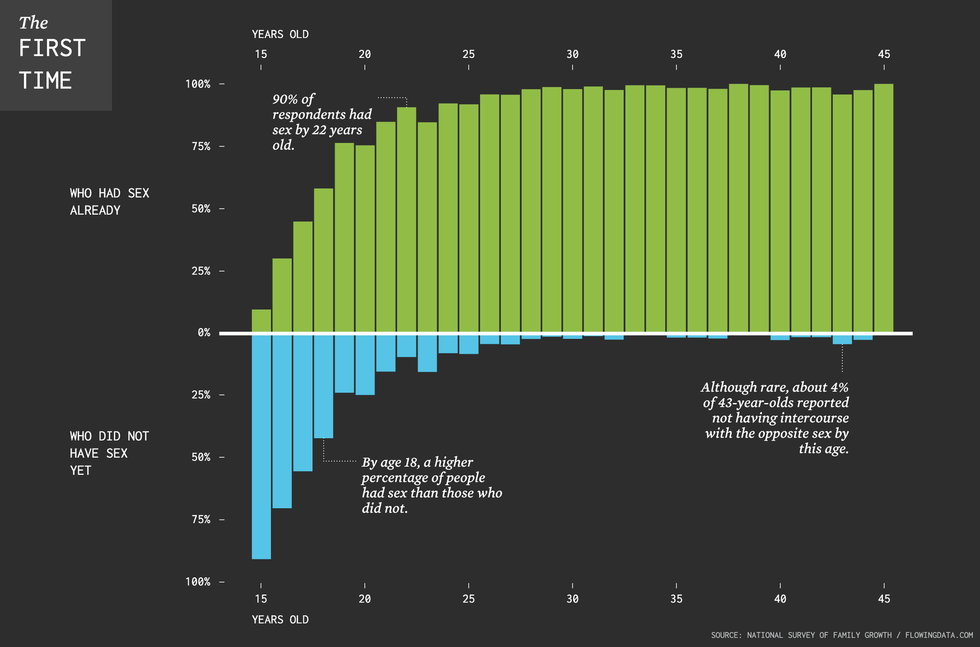

The chart illustrates that between ages 16 and 20, roughly half the population loses their virginity. By age 22, 90% of the population has had sex.

The chart illustrates that between ages 16 and 20, roughly half the population loses their virginity. By age 22, 90% of the population has had sex. A group of young people hold their phonesCanva

A group of young people hold their phonesCanva

(LEFT) Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale and (RIGHT) Ray Bolger as Scarecrow from "The Wizard of OZ"CBS/

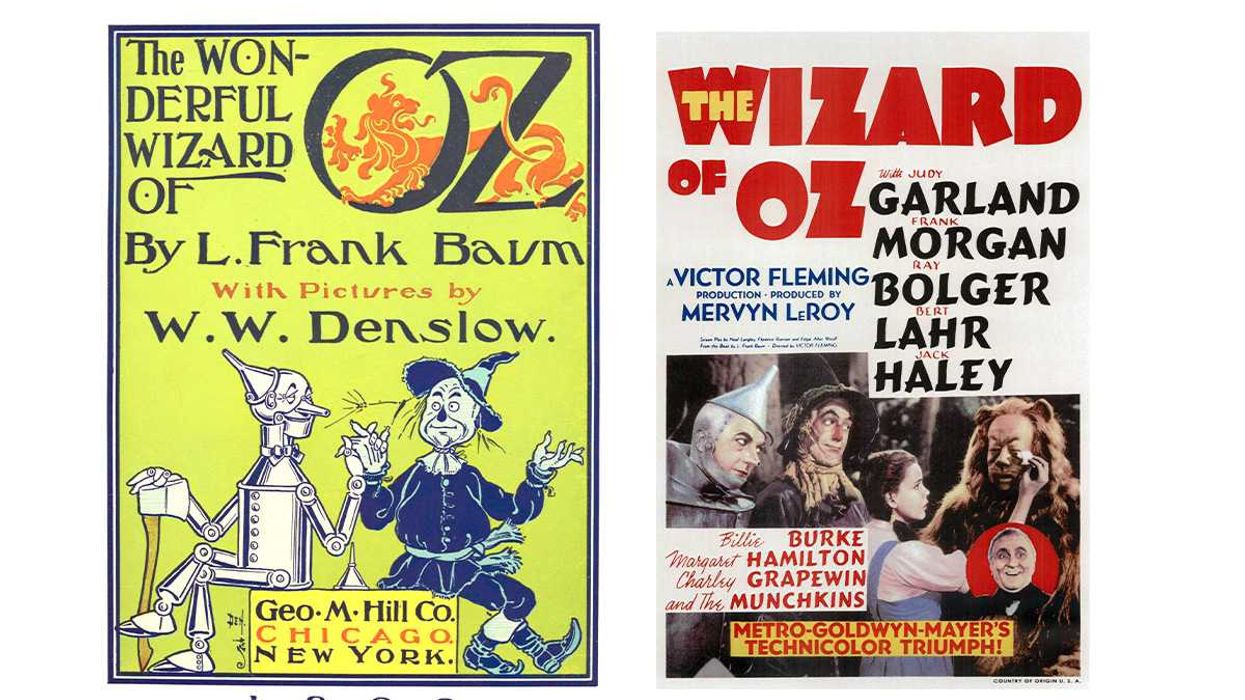

(LEFT) Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale and (RIGHT) Ray Bolger as Scarecrow from "The Wizard of OZ"CBS/  (LEFT) The Wonderful Wizard of Oz children's novel and (RIGHT) The Wizard of Oz movie poster.William Wallace Denslow/

(LEFT) The Wonderful Wizard of Oz children's novel and (RIGHT) The Wizard of Oz movie poster.William Wallace Denslow/

A frustrated woman at a car dealershipCanva

A frustrated woman at a car dealershipCanva Bee Arthur gif asking "What do you want from me?" via

Bee Arthur gif asking "What do you want from me?" via

A couple on a lunch dateCanva

A couple on a lunch dateCanva Gif of Obama saying "Man, that's shady" via

Gif of Obama saying "Man, that's shady" via

Elegance in red.Photo credit:

Elegance in red.Photo credit:  An older woman shows off some bling.Photo credit:

An older woman shows off some bling.Photo credit:  A woman enjoys a beautiful day. Photo credit:

A woman enjoys a beautiful day. Photo credit: