Self-dubbed “the world’s oldest kid,” illustrator, designer, and author LouBrooks is one of those people whose work has helped shape the pop culture landscape of the last 40 years. A self-taught artist whose style is a mashup of 1940s and 1950s comics, pulp fiction book covers, the golden age of advertising and Mad magazine, Brooks' illustrations have been featured in just about every major publication including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Rolling Stone, Time and Newsweek. He has won numerous awards including the Illustrator of the Year award from Adweek magazine. He even redesigned the Monopoly man. His latest project, The Museum of Forgotten Art Supplies, a hat tip to days gone by, is a cheerful exhibition of aged tools of the trade.

GOOD: What led you to create the Museum of Forgotten Art Supplies?

LOU BROOKS: When you think about it, most things that have happened have happened in the past. But bolts of inspiration actually do happen. Georges Simenon used to leave his friends standing on the sidewalk in mid-conversation, yelling, "I'm about to have a book!" In 2006, I was invited to join Drawger.com, an invitation-only sort of "elitist" blog for illustrators, and while setting up housekeeping there, I noticed you could also set up a little "show" about anything you wanted. I thought about how it's all changed so completely, and I thought of the museum. It was nothing more than an inside joke. I began to upload "artifact" images, and was sure that any comments would come solely from other Drawger members, which was true at first. But somehow, it just got very viral very quickly. People from outside the site were sending in images from all over the place, and a little community grew around the Museum.

GOOD: Where have these forgotten art supplies gone? Are they all casualties of the digital revolution?

BROOKS: You would think so. But plenty of them are still being used. I get emails and comments saying: “I still use that thing every day, you bum! How dare you call it forgotten!” Those who take the Museum literally at its word regarding what is “forgotten” are missing some of the fun of it all.

GOOD: Are these forgotten supplies still tools of the trade for you or do you work digitally now?

BROOKS: In the beginning, I inked everything with technical pens and templates. It was all derivative of my production art background. Every black line was shaved to perfection with a #16 blade and on and on long into the night. When I was finally able to reach the same perfection by pushing vector buttons on my first Mac Centris, I thought, “This has all been invented because of me.” I was walking on water, and cured many sick people before donating most all my art supplies to Parsons, and moved out to Northern California. Now, a dozen years later, I’ve kind of made a circle, and am back to inking on paper, then taking it into the Mac and putting it through some closely guarded family techniques. So, it’s a nice balance, and satisfies my tactile cravings for the flex of the pen nib on gritty paper.

GOOD: Of the supplies showcased, do you have any favorites? Is there anything that you’d like to have in the museum that you don’t?

BROOKS: Well, same as most everybody else, a lot of my favorites are the ones that I actually used. They can take you right back to that moment. It can be a lot like hearing that song that was playing when you were slow dancing with Darla Jean Potts. You can smell the Spray Net in her hair. My first job was on the night shift in the art department at a large Philadelphia newspaper. The paper doesn’t even exist anymore. The first thing they taught me how to use was their stat camera, which was so big, it required its own room. You’d set a can of peaches in front of the lens, then touch up the print with pen and ink for a supermarket ad. Coming from parking trucks in a steel mill, I thought I was Vincent van Gogh. They also taught me the PhotoTypositor, which I fell in love with. It was about the size of an antique airplane console, but with cranks and pulleys. You exposed type on a little paper strip, one letter at a time. You could do a whole headline in about 30 minutes, if the machine was well maintained. I’ve carried the PhotoTypositor and stat camera around in my heart ever since.

GOOD: The museum is open to public submission and at this point hosts images of over 400 artifacts. You’ve also incorporated features where artists recount stories from their own careers. Tell us about the community that has sprung up around the museum.

BROOKS: When I finally got the Museum rolling, I admit I was mistakenly expecting a bit of an elephant graveyard where all graphic arts geezers go to die. I was thinking about going there someday to collect the ivory. But I’m happy to say that there’s a solid permeation of young artists besides. After growing up with iMacs and Game Boys, they seem hypnotized at times by any tactile way of doing art.

As far as the community, much of it is rooted in the pre-Mac generation. But don’t forget, not everyone ran out back then and bought an outrageously expensive Quadra and all the peripherals. It was a gradual thing, so the age range of Museum fans is pretty wide. They’re not all geezers whining for the good old days. In fact, some of the geezers say they’re glad those days are gone. Cutting your finger off with an X-acto knife wears on a person after a while.

GOOD: What has the response to the museum been?

BROOKS: I get emails pretty much every day thanking me for the Museum. They can be quite touching at times. They often mention how much they miss the smell of the supplies from back then. It’s funny how smells are so tied in with our pasts. On the other hand, someone wrote me a couple of weeks ago and asked if I could fix her old waxer. She’d be happy to send it along for repair. I’m thinking maybe there’s big money to be made in waxer repair.

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

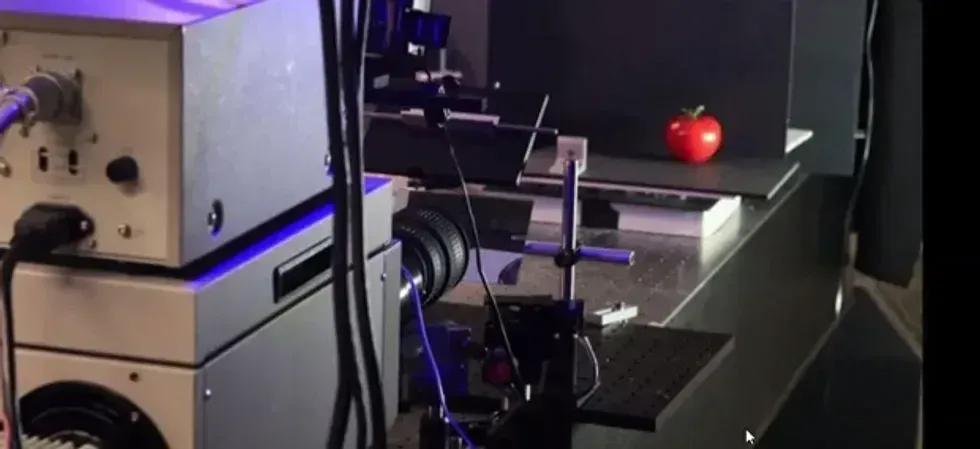

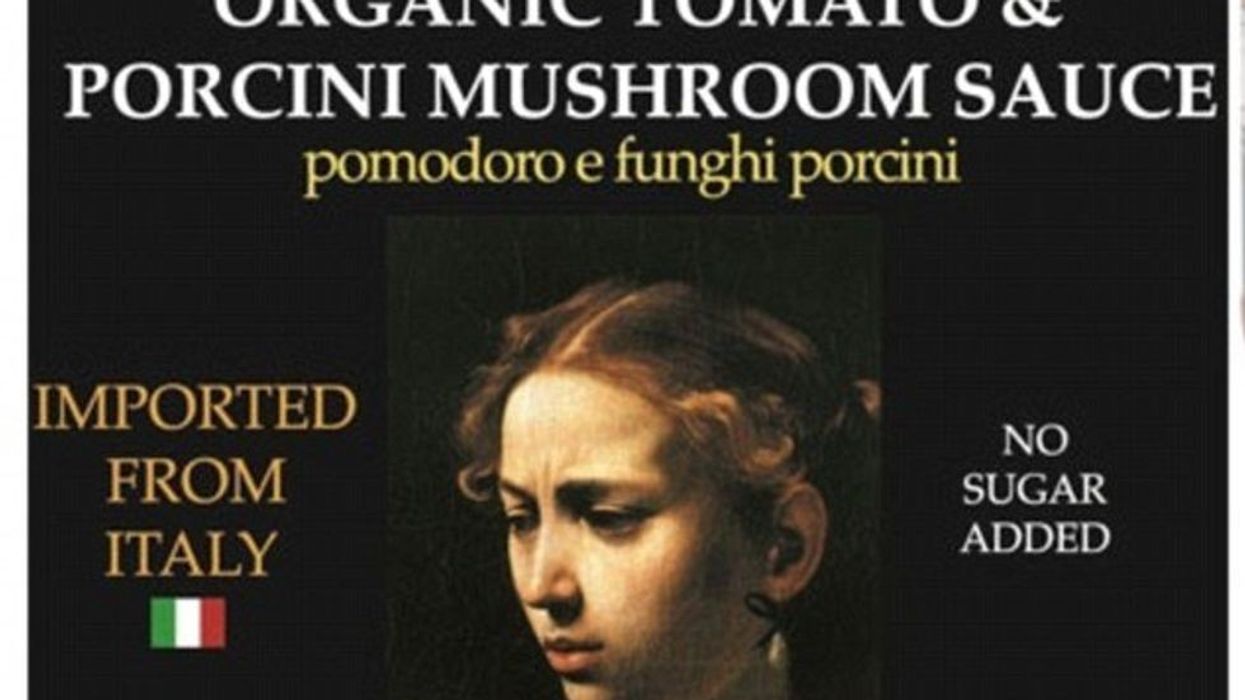

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)