On the night Azim Khamisa learned that his son Tariq had been murdered, he had what he calls an out-of-body experience — a moment that led him to an almost spiritual partnership and a practically otherworldly example of forgiveness.

Tariq Khamisa was murdered 22 years ago in 1995. He was making a pizza delivery to an apartment in San Diego, when he arrived and was confronted by four teenage boys intending to rob him. One of the teens was 14-year-old Tony Edward Hicks. According to Hicks’ grandfather, an 18-year-old that Hicks had been hanging out with at the time handed the teen a 9 mm semiautomatic handgun and directed him to shoot Tariq if he refused to give up his cash or the pizza.

Hicks pulled the trigger at point-blank range.

“When I got the call [from police], my initial reaction was that it was a mistake because I couldn’t go there [emotionally]. So, I quickly hung up on them,” Azim says. Instead, he called his son’s apartment, fully expecting him to answer. He got his son’s fiancée instead. She was sobbing on the phone. The police had gone to the apartment to tell her about Tariq’s death.

“I remember I was in my kitchen. I lost strength in both of my legs, and I collapsed to the floor. Curled up in a ball… I wish I had the words to describe to you how excruciatingly painful that experience was. It felt like a nuclear bomb detonated in my heart, and I’ve never in my life felt pain like that. It was so excruciating. I had my first out-of-body experience,” Azim said.

It was on this night that Tariq’s father says he realized there were two victims: his son and the (very) young person living through circumstances that caused him to shoot someone else. “I believe I left my body and went into the loving embrace of God. I don’t remember how long I was gone, but God sent me back into my body with the wisdom that there were victims at both ends of the gun,” Azim says.

“Tony was born into an environment that guaranteed him a lot of confusion, a lot of misunderstanding, and — potentially, if he made the wrong decision — a lot of violence. When Tony came to live with me, I understood he would need a lot of support,” says Ples Felix, Tony’s grandfather, who took in an 8-year-old Tony (along with his mother) after the boy witnessed the murder of one his favorite cousins by gang members.

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]It felt like a nuclear bomb detonated in my heart, and I’ve never in my life felt pain like that.[/quote]

Within a year of Tony’s arrest and sentencing for Tariq’s murder (he was tried as an adult and sentenced to 25 years to life), Azim reached out to Ples and asked him to join him in creating the Tariq Khamisa Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to ending youth violence by healing those who have suffered from it.

Both Azim, 68, and Ples, 67, meditate several times a day. Azim was raised in Kenya in the Sufi faith, a branch of Islam, while Ples is a Christian who discovered meditation through a Buddhist monk in Cambodia, while on his first tour of Vietnam.

“I started the first meeting with Ples by saying I’m not here to scream for retribution or revenge because your grandson killed my son; rather, I’m here in the spirit of compassion and forgiveness because I see that we both lost a son. My son died and you lost your grandson to the adult criminal justice system,” Azim says.

“The reason I’m here is to tell you that I’ve started a foundation with the lofty mission of stopping kids from killing kids. And while I can’t bring my son back from the dead and there’s nothing you can do to get your grandson out of prison, maybe we can stop other kids from ending up dead like my son or in prison like your grandson. Will you help me? He was quick to take my hand of forgiveness. The first words out of his mouth were, ‘Thank you for reaching out to me because ever since I found out that my grandson was responsible for the death of your son, I went into a prayer closet. Of course I’ll help you.’”

In 23 years of operating, TKF has been creating what they call a “safe-school model” that involves teaching empathy, compassion, and peace-making to middle-school students; the foundation claims to have cut expulsions and suspensions by 70% at a cost of approximately $50 per child. All funds are raised via private donations and grants from private foundations, as well as some public foundations.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]Tony was born into an environment that guaranteed him a lot of confusion, a lot of misunderstanding, and — potentially, if he made the wrong decision — a lot of violence.[/quote]

TKF often kicks off its work with schools by holding a live assembly featuring a conversation between Azim and Ples. There’s also a 10-week in-class curriculum, rooted in restorative justice philosophies, in which students learn how to manage their emotions, make amends, hold themselves accountable for their actions, and exercise empathy and compassion. TKF also establishes what they call a peace club on campus, handled by students, teachers, and volunteers from TKF, which give students the opportunity to lead while building skills in cooperation. TKF’s mentoring program places “peace educators” in schools, and they work one-on-one to support those most in need.

“What gives me hope is that not only are the kids teachable, our kids are hungry for these lessons. We will celebrate our 22nd year in October this year. It’s very gratifying,” Azim says.

Tony will be eligible for parole in October 2018.

“Today he’s a full-grown, strong, focused-thinking man. He got his GED in Pelican Bay State Prison. He’s been in prisons before where there was nothing for him to do. The prison system is a place for people to go and die. Now he’s in Centinela prison; he’s been there for about four years. He’s got a lot of certificates and courses he’s completed, from anger management to writing and administrative work, and he says he’s interested in getting a degree in child psychology. He says wants to be able to help children,” Felix says.

Self reflection.Photo credit

Self reflection.Photo credit  Older woman touching hands with a younger self.Photo credit

Older woman touching hands with a younger self.Photo credit  Sign reads, "Regrets Behind You."Photo credit

Sign reads, "Regrets Behind You."Photo credit

Couple talking in the woods.

Couple talking in the woods. Woman and man have a conversation.

Woman and man have a conversation. A chat on the couch.

A chat on the couch. Two people high-five working out.

Two people high-five working out. Movie scene from Night at the Roxbury.

Movie scene from Night at the Roxbury.  Friends laughing together.

Friends laughing together.

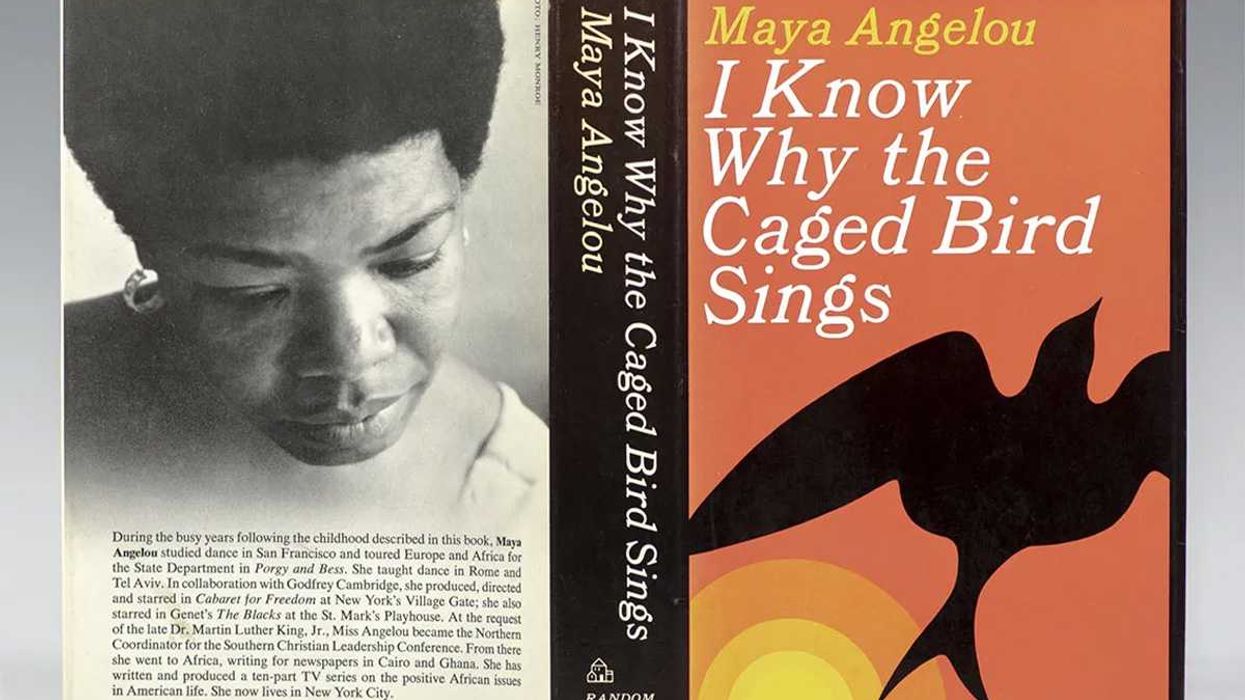

Maya Angelou reciting her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993.William J. Clinton Presidential Library/

Maya Angelou reciting her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993.William J. Clinton Presidential Library/  First edition front and back covers and spine of "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings."Raptis Rare Books/

First edition front and back covers and spine of "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings."Raptis Rare Books/

Tow truck towing a car in its bedCanva

Tow truck towing a car in its bedCanva  Sad woman looks at her phoneCanva

Sad woman looks at her phoneCanva  A group of young people at a house partyCanva

A group of young people at a house partyCanva  Fed-up woman gif

Fed-up woman gif Police show up at a house party

Police show up at a house party

A trendy restaurant in the middle of the dayCanva

A trendy restaurant in the middle of the dayCanva A reserved table at a restaurantCanva

A reserved table at a restaurantCanva Gif of Tim Robinson asking "What?' via

Gif of Tim Robinson asking "What?' via

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva