Sheets of rain traverse Rotterdam’s late afternoon sky as I prepare to leave designer Daan Roosegaarde’s “Dream Factory.” He and I linger in front of the sliding glass industrial door, peering out, and I wonder if I should make a break for it. “Does it always rain this much?” I ask regarding the inhospitable late-summer weather of the Netherlands. “It does,” Roosegaarde replies with a non-challant grin, implying this is a regular occurence. Roosegaarde offers me a low-tech solution—an umbrella emblazoned with words “World Economic Forum, Davos” where he was a guest last January. This small gesture acts as a metaphor for the ways the young artist’s impressive oeuvre of design solutions interact with, and react to, nature’s unpredictable ways.

At just 36, he already boasts an expansive list of temporary and permanent “interventions.” These creations sit at the intersecting point where technology, architecture, and the natural environment meet. Many of these are grand artistic expressions of what tomorrow could look like when thinking outside of the box, while others solve real-world design problems, making the lives of urban dwellers easier. Take, for instance, Waterlicht, an immersive “virtual flood” of blue LEDs. The installation took over Westervelt, NL this year as an engineered interpretation of the northern lights, showing how high water would rise without the country’s elaborate system of dikes in place. In Eindhoven in 2014 Roosegaarde conceived the solar-powered “Starry Night” bike path, an interactive homage to the city’s most famous resident, Vincent van Gogh. In Davos—where my umbrella traveled from—guests were invited to walk through “Dune,” a system of sound and motion-sensitive lights that reacted to passersby. Ironically, many of these dense panels lined the way to discussions exploring the future of energy at this pivotal annual Forum.

Roosegaarde’s latest manifestation, and why I’m visiting the Dream Factory today, is the Smog Free Tower. The world’s “largest air purifier,” its goal is to provide respite to residents in polluted cities around the world. Originally intended to debut in Beijing, he came up with the idea for the Smog Free Project while visiting the Chinese metropolis a few years back. He realized he couldn’t even see what was right in front of him due to the area’s deplorable air quality. “For me it’s very weird that we accept this,” Roosegaarde remembers, reflecting on the collective global apathy towards contaminated environments. Working on the tower concept for three years with a team of designers and experts, he now hopes to harness technology and civic engagement to challenge the status quo.

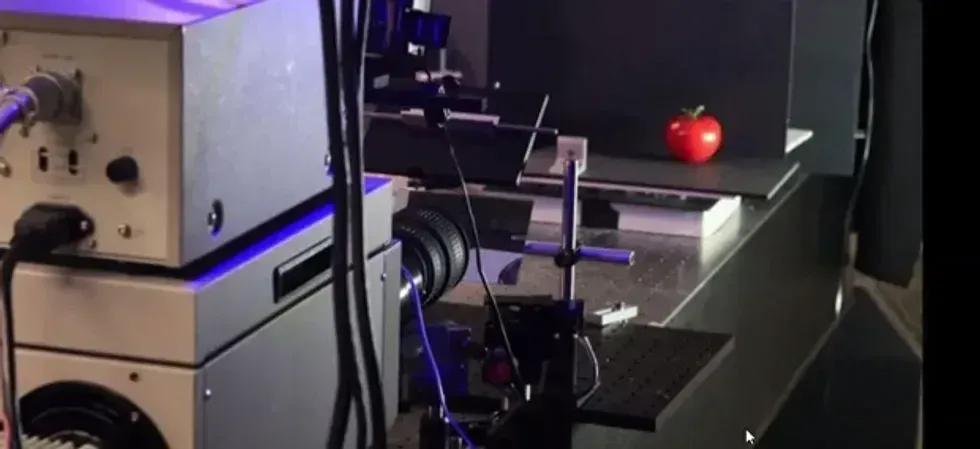

Installed in an underdeveloped green field in back of his studio, the futuristic 7-meter-high Smog Free Tower hums and purrs, sucking in Rotterdam’s soot while pumping out clean air. With its chemical plants, oil refineries, and heavily trafficked shipping port, Rotterdam has some of the worst air quality in the Netherlands, if not the world, making it a prime testing ground for environmental innovation. The structures' facade—comprised of several white slats angled at varying degrees, resembles a much sexier version of household window blinds. And like a wizard behind the curtain, Roosegaarde can easily control it with a remote from the safety of his office should it get too rainy (like today).

Inside the framework, the functionality is that of a conventional air filter, using as little energy as it would take to heat an electric tea kettle. Filing cabinet-style drawers collect toxic particles to be “harvested” once a week for another part of the Smog Free Project: jewelry made from the dust packed into cubes and resin-coated. This element is just as important as the mechanical component because it encourages everyone to be a part of the solution. When you purchase these Smog Free rings or cufflinks you are meant to share your values on your sleeve, sparking conversation as well as financially contributing to the project.

Around the tower’s perimeter is space for people to gather while enjoying air that’s 75% cleaner than elsewhere in the region. “We’re designing it sort of like a fireplace,” he explains. “People will go there and meet and share ideas about how they would like the whole city to be smog free.” In this way, the tower acts as a conversation starter, rather than a definitive tool to fix the pollution problem. As Roosegaarde puts it, “It’s not the final solution, it’s the enabler.” The hope is this conversation will happen all over the world as the tower, post launch, travels to other cities like Beijing, Los Angeles, and Mexico City.

A pointed emphasis on community involvement is also the reason Roosegaarde took to Kickstarter to crowdfund the Smog Free Project, rather than approach a corporate sponsor. “It was important that it was shared, so people are standing behind it,” the artist elaborates. “It’s the notion of creating a collective. Without the people it would be meaningless. It would just be a machine—a beautiful machine, but a machine nonetheless.”

Roosegaarde’s “beautiful machine” is just one of the many inspired ideas to come out of the Dream Factory since it landed in Rotterdam’s emerging Nieuwe-Mathensesse neighborhood in July. The studio, like its satellite in Shanghai, acts as an incubator for ideas turned reality, and has an adjacent garden spanning a full city block. This space is often used for prototyping and connecting with nature. Behind the expansive green garden is one of Rotterdam’s famous rivers, the Nieuwe-Maas, and next to that, the largest cargo port in Europe, which connects the country to the rest of world.

It’s easy to see why Roosegaarde chose this location to build his greenhouse-style studio, which occupies a defunct power plant. There are sprawling brick maritime buildings, some neglected, others turned into condos. From here you can feel the significant industrial history and the harbor economy that continues to power Rotterdam. (The port once owned the title of the world’s busiest until Singapore and later Shanghai took that claim.)

The charming grittiness of these streets along the water has a different vibe than the city center. The latter was redeveloped in the ‘80s and ‘90s after being left in neglect since World War II bombing nearly destroyed the whole area. Since then it’s been a center for architectural innovation, with everyone from Rem Koolhaus to Ben van Berkel designing for the city.

In fact, pulling into Rotterdam Centraal by train from Amsterdam it feels as if you’re stepping into a 3D rendering of what a post-war, post-apocalyptic urban regeneration might look like. Everything in the city feels new, down to the railway station that was finished last year. In the middle of town sits prominent artist Paul McCarthy’s massive “Buttplug Gnome” sculpture, which set blogs and art publications ablaze last year. This cheeky indicator shows that along with regrowth, Rotterdam encourages experimentation with a wry sense of humor.

The Dream Factory was given such an optimistic moniker because, as Roosegaarde says, it’s all about “dreaming and doing.” He and his “shapers”—a mini-army of architects, technical designers, and process managers that work out of the Dream Factory—are conceptualizing the landscapes of the future. This can mean different things on different days. Sometimes ideas are purely conceptual, but others have the intention to become tangible. “We look for the radicalness in things, but at the same time we build it,” he maintains. “We know the smart city discourse is dominated by technology and not people. That’s wrong, so we should sort of infiltrate that.”

Dreaming is not something city planners and government authorities often embrace. But Roosegaarde is one of the world’s few creatives in the position to make artful change on a mass scale. Because of his innovative approach to urban predicaments, he’s often given free rein. Both officials and communities celebrate him for his ability to deliver impressive fixes (or at the very least, out-of-the-box suggestions). For instance, instead of street lamps, in “Glowing Nature”, an upcoming project from the Dream Factory, he will create a series of illuminated trees using organic material luciferin—an element found in jellyfish and fireflies. Sitting in his Dream Factory, he doesn’t see himself in an elite position, though he’s aware of the good he and his team can manifest. “The impact of new ideas is larger than ever. The impact of good people with good ideas can be just as large.” Sometimes it takes people time to come around to his forward thinking, but they usually do. “In the beginning people say it’s not possible, it’s not allowed. And once you go through that, people say ‘Oh this is so good, why didn’t you do that before?’”

That was the case with Smog Free Tower, which Roosegaarde says five years ago was unthinkable. But as we gaze on it from the open door of his Dream Factory it seems like a design solution so necessary that we can’t help but wonder: why wasn’t it done before?

The rain doesn’t let up so I make a run for the water taxi waiting by the river. As our boat pulls away from land I take a laser scan of the Smog Free Tower. Its inorganic architecture is juxtaposed next to a series of winding vegetable gardens, and looks somewhat like a space-age vacuum cleaner.

I think about the last question I discussed with Roosegaarde—a meditation on his personality and goals. “What defines me is my future,” he told me. With the Smog Free Tower up and running as of September 5, whatever form his future takes, it will certainly be a cleaner place than today. By Roosegaarde’s calculations, 75% cleaner to be exact.

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

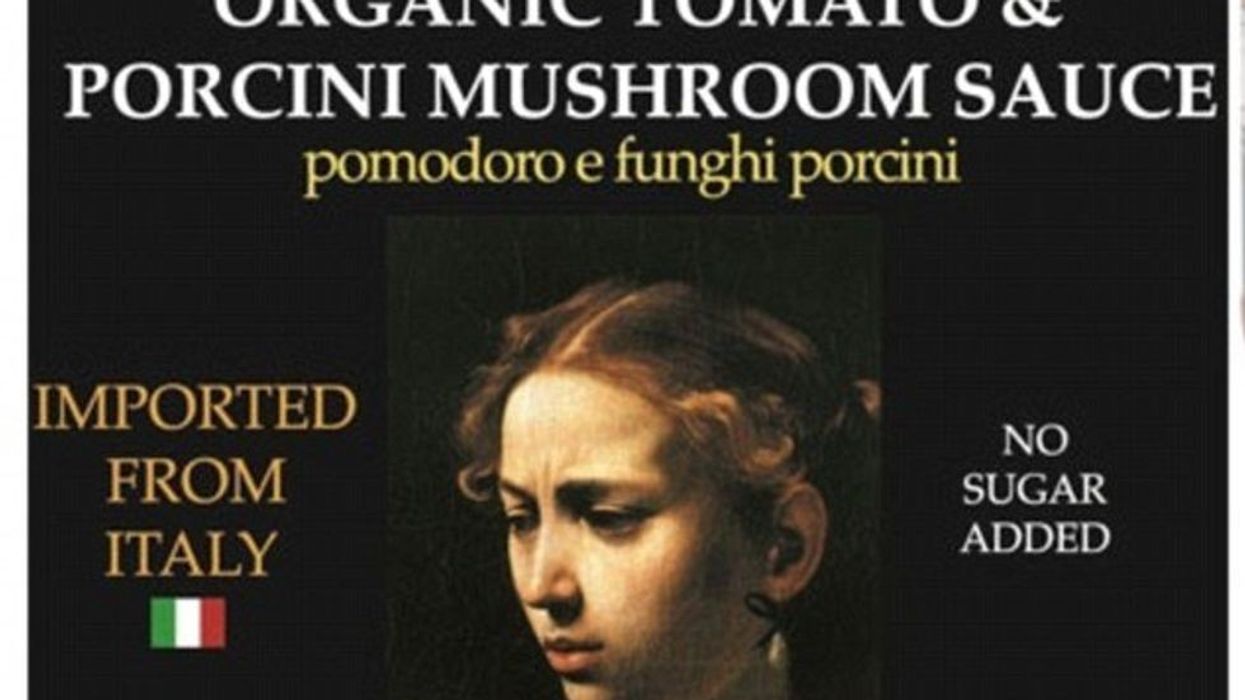

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)