Today the long-awaited, much-heralded Apple Watch goes on sale. Touted by the company as its “most personal device yet,” it promises everything from quicker “interactions and technology” to a more intimate experience with our watches, whatever that might mean. The tech juggernaut, known for its cult-like devotion and grandiose live-streamed announcements, welcomes new product launches like Elvis just entered the building, with long lines of gadget-jonesing fans camped at local stores, and hysteria quickly hitting a fever pitch. Along with online launch countdowns and mass speculation, the company’s hype always raises questions of whether their latest product will bring on the future of “X” —whether it’s tech, retail, communication, or, really, take your pick. Basically, anything Apple does is a big fucking deal.

The Apple Watch, which comes at several price points, from the “moderately priced” $350 Apple Watch Sport to the $15,000 luxurious Apple Watch Edition, has received pre-orders from over 2.3 million consumers and counting. Geek-chic watches have been around for decades, but the design of the iWatch, masterminded by Apple Senior Vice President of Design and usability “god” Jony Ive, is expected to break the mold of what we can expect from all future time-telling gadgets, not just in terms of functionality but also mass production. This great leap forward, however, has just as much a foot in the past as the future—specifically, in an influential German design movement that grew out of the chaos of WWI, aiming to reinvent a more ordered and just society through great design. The Bauhaus school shifted between Weimar (1919 -1925), Dessau (1925-1932) and Berlin (1932 -1933) during Germany’s most pivotal years, and acted as an innovation incubator, not unlike Apple’s Design Lab. In both instances, a team of dedicated practitioners thought they could alleviate the alienation of modern society through more personal consumer products, clean lines, and user-friendly interfaces. In other words, a revolution centered on aesthetics that benefitted the people.

In 1915, the visionary Walter Gropius, considered by many to be one of the first masters of modern architecture, began to develop his plan for a "purely organic building,” which declared “its inner laws, free of untruths or ornamentation.” This “building” was more of a metaphor than a physical object, and extended beyond the concept of architecture to encompass product design, packaging, and even furniture. Not unlike Steve Jobs, Gropius was single-minded, and could be unwavering and brutally direct in his mission. As the head of the Bauhaus school in Weimar, he recognized the need to surround himself with a team of talented collaborators, instructors, and designers, on-boarding some of the biggest names in contemporary arts, including Paul Klee, Josef Albers, Herbert Bayer, Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and Vassily Kandinsky—names that history would prove incandescent creators.

Translated directly as “house of construction,” the Bauhaus was founded on the principle of integrating a total, holistic form of creation in which all arts specialization could be brought under one, interdisciplinary umbrella. The Bauhaus also had a profound influence on the direction of all subsequent graphic, interior, and typography design—moving the art world from the cramped industrial revolution into an era of smooth, accessible lines, and paving the way for Modernism. Gropius’s educational methods, and the system he put in place for higher learning while at the helm of the Bauhaus, also created an ordered academic system that can still be felt in many contemporary art schools.

The Bauhaus’s leaders believed even the most unglamorous and practical items should be both beautiful and useful. Though much has been made of Ive’s admiration of Braun's Dieter Rams, the prolific designer behind many of the century’s most important electrical products, he was also likely to have been influenced by the “break the rules and rebuild them” spirit of the Bauhaus. The Rams/Ive link, lazy shorthand for a broader art history few are willing to wade through, was recently called out in an insightful piece by The New Yorker: “At Braun, Dieter Rams had relieved consumer electronics of the need to pose as furniture. A radio could be a box. Apple’s instinct, at this moment, was to do the reverse: to domesticate a machine still largely associated with technical tasks and the workplace.” As writer Ian Parker continues, “Ive greatly admires Rams, but his debt to him has sometimes been overstated, and it’s worth noting a difference of manufacturing scale: Rams’s Braun products sold in the thousands, occasionally the millions; Apple has sold one and a half billion things designed by Ive.” Rams, though seminal to design history, was one man who created very specific things for a very specific genre. The Bauhaus, on the other, created entire cities.

Juliet Kinchin, Curator of the Department of Architecture and Design at MoMA, who also oversees MoMA's historical design collection, is unambiguous about the Bauhaus’s influence on modern design. “The Bauhaus methodology really did break the mold,” she says. “It's about recognizing the need for new kinds of industrial designers or product designers.” It’s also about “that idea of really joined-up thinking about product design, industrial design, and social context.” As Kinchin highlights, Ive would likely have been introduced to concepts of the Bauhaus while in university. “Certainly the kind of foundation studies [Ive] would have encountered studying art and design in school and in New Castle Polytechnic [would gave been influenced by the Bauhaus]. That comprehensive idea of studying not only the basic principles of simple forms and colors, but also how things are made.”

Why are the concepts behind the Bauhaus still persistent? “The idea of trying to simplify our lives is a very powerful one when we're under such pressure to consume, says Kinchin. “The idea of very immediate communication with the user is part of a philosophy of design that really tries to directly connect user with user experience.”

Daniel Arsham, a contemporary designer who bridges the gap between high art, new media, and popular culture, and has worked with everyone from choreographer Merce Cunningham to Pharrell, also sees the correlation. “Design over the last 25 years has been all about reduction,” Arsham told me by phone. “‘Less is more’ was a Bauhaus idea. And it's definitely [in the minds] of the designers who have been making the products that we are using today.” This subconscious training in minimalism is no accident. “All of the curriculum for every art school in the country comes from an idea that was developed at the Bauhaus. Which is basically 2D design, which we call performance. It doesn't matter which school you go to, that is going to be taught. Also color theory, which comes from Joseph Albers of the Bauhaus, had a profound influence on education, and [often] gets downplayed.”

Claudia Perren, Director of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, believes that the movement's cross-disciplinary experimentation set a precedent for our current design culture. “The Bauhaus revolutionized artistic and architectural thinking and production worldwide,” she says. “The school pursued nothing less than the revolution of everyday life in the 20th century. It has influenced the idea and our understanding of design, but its legacy is even more than a specific concept of a functional design for all.”

“The Bauhaus was more than a cultural movement, it touched upon all spheres of life and was a social movement for a better life with all its ambitions and failures,” says Perren. “The Bauhaus is still an inspiration for designers and artists worldwide, less because of its specific designs or architectural approach but more because of its holistic, avant-garde ideas.”

New media artist Anthony Antonellis is one of those inspired both by modern technology and the Bauhaus’s approach toward design education. Antonellis, who gained notoriety for his tech-inspired work and turning himself in to a cyborg by implanting an RFID chip in his arm, studied at the current Bauhaus Dessau. He explained to me that the Bauhaus system, handed down by Gropius, is still resonant today. “I arrived where I am as a direct result of my studies in Weimar. I studied alongside other artists, students in media, architects, craftsmen, product designers, graphic designers, and all these disciplines taught and learned from each other in a profound exchange of ideas and approaches.” So whether you pre-ordered your watch online, or are part of the horde checking it out in stores, when you snap on your Apple Watch just remember: It took literally thousands of brilliant thinkers and over a century of work to bring you that tiny, dazzling device.

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

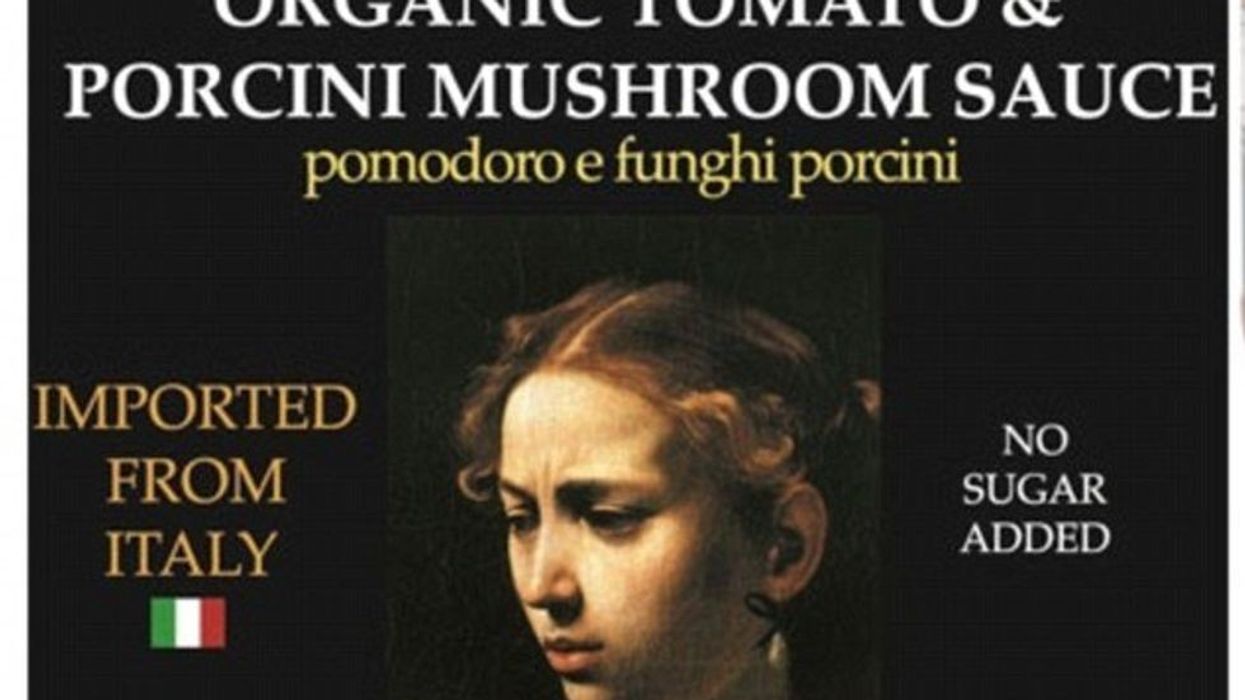

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)