You’re feeling groovy. Across the country in San Francisco, the Summer of Love is blossoming, but in New York City, plenty of freaky things are happening, too: anti-war marches, a Central Park “be-in”…in fact, what is this right here? You stop and look through the window at 220 East 60th Street: “In Dispensable Disposables.”

Is that a goat in there? Is that a white, bearded goat being fed an orange dress? Why is a man in a dark suit trying to make a goat eat a dress? Wondering about your mental state, you peer inside.

Flash!

You’re not tripping. A photographer snaps a shot of, yes—an actual goat.

The animal’s name was Lorrie. What you would have stumbled on, had you been taking such a stroll down East 60th Street on June 9, 1967, was the grand opening of a store dedicated to selling nothing but disposable clothing, mostly dresses made of paper. There were racks with glow-in-the-dark shift dresses for $15 and a red, gingham-checked couture evening gown by designer Ann Pakradooni for $150. Lorrie was a promotional stunt, designed to show the ephemeral nature of the garments, and the man in the suit was William Guggenheim III, 28, proprietor of the shop and scion of the Guggenheim family.

Mid-1967 was the apogee of paper wearables. You would have seen news of this peculiar revolution. There was a feature in LIFE magazine titled, “Wastebasket Dresses.” One company’s fabric, Kaycel, had “a slightly bumpy surface resembling paper toweling, though its next-of-kin is actually Kleenex.” According to the magazine, Kaycel was made up of 93 percent cellulose wadding—like Kleenex—plus seven percent nylon, pressed inside to impart strength and “drapability,” but not impairing an owner from shortening the dress with a pair of scissors or lengthening it “by pasting on trim, like lace on a valentine.”

At an annual shareholders meeting, the chief executive of a joint venture between Kimberly-Clark (among their products: glossy, coated paper for Playboy magazine) and textile-maker J.P. Stevens Co. called paper wearables “a significant field.” Although total paper garment sales were only around $3 million for 1966, a tiny share of a $30 billion women’s apparel industry, 60 manufacturers had rushed into the paper fabric business, and there were predictions that revenues would soon grow to $50-$100 million a year.

A satirical piece on the trend in The New York Times even offered a limerick:

A daring young girl from St. Paul

Wore a newspaper dress to a ball;

The dress it caught fire,

And singed her entire

Front page, sporting section, and all.

It seemed, in that era when so much else was changing, that clothing was too. “The answer to laundry in outer space,” a magazine article declared, two years before the first manned moon voyage. “Democratic” (small “d”) another proclaimed, noting that dresses worn a half-dozen times and then tossed were feminist, eliminating the drudgery of cleaning. One company sold them in a can. Campbell’s Soup took Andy Warhol’s cue and printed its own soup can image paper dresses. Anyone could mail in a few proofs of purchase and a dollar to receive a wearable Pop art gem.

And then, within two years, it all fell apart. By the fall of 1967, In Dispensable Disposables was out of business, and Guggenheim out more than $10,000. The Kimberly-Stevens venture was dissolved in 1969. Those Campbell’s Soup dresses are now museum pieces.

This is not exactly a story like the one told in the documentary, Who Killed the Electric Car?, in which a corporate conspiracy knocked the legs out of a world-changing environmental technology because it threatened established oligarchies. The story of who and what killed paper clothing involves a combination of the whims of fashion, bad public relations, and a lack of economic pressure to solve its technical challenges. But now, with the fashion business stripping natural resources along with the health and dignity of workers, and with a resulting awareness telling consumers that buying five bleached white v-necks at Old Navy for $10 might be as unhip as failing to recycle a six pack of beer cans, even some fashion cognoscenti are starting to search for a better way.

Could paper and other fabrics with a shorter, less environmentally damaging lifecycle be the way forward?

“We are disposably using items that are not disposable,” said Andrew Morgan, director of the fast-fashion exposé documentary, The True Cost.

In the mid-1960s, during In Dispensable Disposables’ run, 95 percent of America’s clothes were made domestically; by 1990, it was 50 percent; and today, 97 percent are made abroad according to the American Apparel and Footwear Association. Tightening the timeline, roughly 80 billion pieces of clothing are purchased globally in a year—400 percent more than a decade ago, and three out of four of the worst garment factory disasters in history happened in 2012 and 2013, including the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh, killing more than 1,100 workers. Meanwhile, the world’s top three fast-fashion brands—H&M, Zara, and Fast Retailing (owner of Uniqlo)—boasted 2014 sales of more than $56 billion.

Relegated for four decades to hospital gowns and other utilitarian uses, there is a case to be made that disposable clothing in the form of paper or other materials may offer a solution to a crucial quandary: how to change fashion without killing it.

Paper clothing, like marijuana, free speech, and free love, was not a completely new idea in the 1960s. It goes as far back as the 18th century, when fabric and clothing were expensive, and stylish women began to use paper instead of cloth for the detachable collars and cuffs of dresses. These parts of a woman’s outfit normally required the most laundering, and by switching them out, a whole new look could be achieved without buying an additional dress. The trend picked up again in the 19th century, when the price of traditional cloth goods spiked.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]We are disposably using items that are not disposable,” said Andrew Morgan, director of the fast-fashion exposé documentary, The True Cost.[/quote]

“During the 18th and 19th centuries when clothing and fabric was expensive, and you didn’t throw anything away until it was in shreds, you can get a sense of the novelty paper would have had,” says Colleen Hill, co-author of Sustainable Fashion: Past, Present and Future. Women could achieve a completely fresh appearance for a fraction of what a whole new garment would have cost.

Most environmentalists who have turned their attention to the emergency of apparel have concluded that there is only one logical place for us to end up, likely by necessity when peak oil crashes and container ships can no longer chug cheaply across the seas. The simplest solution, propounded by the likes of author Courtney Carver and her Project 333—living with only 33 clothing items for three months—as well as the blog Unfancy, is that we must pare our wardrobes down to five or six outfits and little else. If an item tears or needs letting out, a nearby tailor handles it.

But what if there was another way—one that might better dovetail with what Jessica Goldstein described on ThinkProgress as “the all-American pastime of seeking affirmation and joy through consumption, instead of simply stating that it shouldn’t exist?”

A shopper considering a shirt at a chain store might recall that everything he’s ever bought there except underwear has, after a wash, been ill-fitting and was quickly sorted into the only-wear-if-everything-else-is-dirty drawer until eventually, most likely in late December, it, along with other items that met a similar fate, is tossed into a garbage bag and toted to a charity store where he collects a receipt for tax purposes—an accountant having once instructed him that a garbage bag full of clothes is worth about $250 in deductions.

While the average American gets rid of 82 pounds of textile waste each year (which includes shoes and bedding, along with clothing), according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), only 12 pounds of that is either recycled or reused, leaving 70 pounds per person—21 billion pounds as a nation—rotting in landfills. Meanwhile, only about 10 percent of the clothing that is donated to thrift stores actually sells, says industry insider and used clothing merchant, Adam Baruchowitz. The rest is shredded into rags for industrial use, recycled, or, most likely, passed through dealers who flip it overseas, everywhere from the Caribbean to Africa, where any hope of a significant indigenous textile industry is torpedoed by the never-ending bales of used stuff arriving in ports, and where shoppers, conditioned to the plenty, are becoming increasingly picky themselves, leaving out-of-fashion stuff to their own dumps. The earth is choking on fast fashion.

If all things were equal, there aren’t many fashion companies that would use anything other than the most ecologically responsible fabrics. But it’s extremely difficult to measure fabrics against each other on an environmental scale.

“Clients always say, ‘We want something more sustainable,’” says Sarah Hoit, a scientist at Material ConneXion, an international materials consultancy. “But sustainability is a really wriggly beast. There are so many metrics. Can I reclaim these fibers and turn them into carpets or something?”

An industry group called the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) is one of many organizations, like the National Resources Defense Council, attempting to codify and compare clothing manufacturing impacts. Their index asks which fabrics cause the least environmental harm to produce, measuring only energy, water and land use, waste creation, and toxicity during its lifecycle.

The SAC gives each material a score, 50 being best possible and zero being worst. Conventional cotton fabric, the backbone of fast fashion, is at 20.4, well below Tencel, a eucalyptus-based fabric at 30.2, and far worse than what SAC’s chief executive Jason Kibbey says is the closest comparable on the index to paper fabric—a corrugated box—at 33.0.

Doing the math: Cardboard is 61 percent better than cotton in this respect. Kibbey points out that other factors not included in the index might make cotton better, like the fact that consumers are likely to wear a cotton garment more times than a paper one, and that the fabric cost is only a small factor in the total cost of a garment. There’s also the problem that, unless you’re dressing as a robot for Halloween, you’re not going to wear a box, which, technically, is a “non-woven” textile, like the old paper dresses.

Cotton, wool, and nearly everything we wear now is woven, an industrial process that takes minutes to produce each meter of cloth. When we use an overnight mail envelope we are using a non-woven fabric, far less expensive because 30 meters of it can be extruded in a minute. There have been improvements in the technology since the 1960s, especially with a process called “air-laid paper,” which is used now for high-quality paper napkins, and is so easy to dye it would seem ideal for an adventurous fashion designer to work with. But until a designer makes an inspiring runway-quality dress out of it, you aren’t likely to wear any non-woven garments outside a hospital room or a factory.

I learned this by buying a package of disposable underwear, “ideal,” the ad copy boasted, “for travel, sauna, and sports.” It was not. I wore it as I conducted a few interviews for this article, but could not last two hours. Made of “extra soft polypropylene,” it was like wearing a coffee filter and rubber bands. My sensitive parts were as irritated as if I was sheathed in a dull cheese grater. Then I tried writing while wearing one of the only other types of “disposable” garments on the market, a set of white, hooded “superpolymer” coveralls, $10 on Amazon—designed for car painters and fiberglass workers. “When incinerated,” the advertising copy assures, “Superpolymer Coveralls are reduced to CO2 and water.” I lasted longer in it than in the underwear, mostly because the suit entertained houseguests who said I looked like a member of Devo—a New Wave band who famously wore Tyvek suits and 3D glasses in the late 1970s. I had to drink 10 glasses of water to replenish myself from sweat loss when finally I shed it.

As I experienced firsthand, there are limitations to eco-friendly fashion. Marci Zaroff, a pioneer in the production and distribution of sustainable fabrics, recalled when the industry was experimenting with seaweed textiles. “It was fun,” she said. “But literally if the textile got wet, you smelled like the ocean.”

We can do better, and already are. In 2014, Korean students in Seoul and, separately, designer Francis Bitonti in Brooklyn, used a $2,800 3D printer to create fascinating, almost hypnotizing, lines of high fashion dresses. Their efforts affirm that fashion, an art form often obsessed with leading society forward, is not entirely failing in the face of its current challenges.

Both efforts used printers built in America by Makerbot, filled with standard spools of affordable PLA resin, a cornstarch derivative. On the SAC scale, fabric spun from PLA (a more processed substance than the printers use) scores a 25.7, only a few points short of organic cotton fabric. To make the dresses, the printer spits out geometric links one by one that the designer chains together by hand, eventually “weaving” a plastic, but airy, garment, more like a wearable sculpture than a dress.

Apps on Makerbot’s website enable printing of bracelets and rings on printers costing as little as $1,400. Take this homemade fast fashion into the future: Imagine you need a dress for your cousin’s wedding. You go to your favorite designer’s website, pay a fee, and download a file. Load a spool of DuraWeave2018 into the 3D printer and presto—a dress emerges. Maybe you wear it a second time, maybe you don’t. It’s recyclable. Sure, someone has to make the printer, the paper, and the ink and get it to you. I don’t have a full lifecycle analysis yet for this hypothetical future.

Even Kibbey of SAC admits, “If you are to look into the future, apparel companies are looking at how is 3D printing with some aspect of recycling, how will that play into sustainability.” But, he warns: “If you take the same supply chain you have now and just replace the cotton fabric with single-use paper clothing, it would be a disaster.”

Fast fashion is already a disaster. Paper clothing won’t solve everything, but each well-designed outfit extruded for pennies in a domestic factory or by a home printer that could manage to feed the fashion itch of a consumer would be an incremental improvement.

So why didn’t it work a half-century ago?

According to accounts, paper dresses stopped being en vogue because of horror stories about women being de-clothed by rainstorms and paranoid of fire. But dig into the media of the period, and there were fancy balls featuring paper attire and stories on the durability of the fabric—even enduring a test where one woman did housework in her garment every day for a month—and fabulous accounts of the creativity and whimsy paper afforded. In fact, in the 1960s, when a good portion of apparel was still sewn in the United States, the low cost of the paper fabric did make a difference in the final cost of the product even though every other aspect of production was similar to woven cloth. “Dresses,” according to a chapter called “Paper Clothes: Not Just a Fad” in the 1991 book Dress and Popular Culture, “were made in numerous prints and colors, and could be purchased or made on a whim; it was affordable to be daring.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]Imagine you need a dress for your cousin’s wedding. You go to your favorite designer’s website, pay a fee, and download a file. Load a spool of DuraWeave2018 into the 3D printer and presto—a dress emerges.[/quote]

Even without the truly mass production that could have driven down the price, in 1967, Kaycel retailed for 50 cents a yard and hand-printed fabric from Paperworks was 25 cents. Printed cotton was around $1 a yard. A line of “Poster Dresses” made from paper and splashed with images of a new Allen Ginsberg poem and a rocket launch were $3 each—around $20 in today’s money with inflation, so, yes, a bit pricier than the $9 polyester skirts Target puts on sale regularly. But there was anticipation that a heat sealant would be developed to eliminate the costly need for sewing, allowing paper garments to be produced and sold in tear-off rolls like toilet paper.

So, what really killed paper clothing? In a 10-minute conversation, Guggenheim, the one-time owner of In Dispensable Disposables, managed to come up with a half-dozen conflicting explanations. The simplest—“It’s like what killed the Pet Rock? It was a fad for its time.”—is too pat. Even in the middle of the Pet Rock craze, everyone knew it was a fad, and profits went to support the disabled. Big companies and serious designers believed paper clothing would last, and they invested in it.

Another of Guggenheim’s explanations for his store’s failure is more salient. “It was a fun thing for the summer. It was in New York City and in the winter it became cold and they weren’t warm enough to wear.” What about the rest of the country, then? The idea that women in San Diego or Singapore might have remained fashionable in wood pulp through December was not the concern of the designers.

Guggenheim took another stab: “It was inexpensive originally and that was fun. But then it went up in price because big name designers would add one dress to their lineup and make it 75 to 150 dollars—back then!—and how many people can afford that?”

Paper clothing was supposed to cost next to nothing, but the fashion industry made the most fashionable choices expensive, and at the first dip in the market, caused by a confluence of the northeast winter and apocryphal stories stoking fears of the dresses disintegrating in a drizzle, retailers bolted. Then came one of the ugliest eras in fashion history, reliant on the growing use of another space-age fabric—polyester—and emblemized by the beige or powder blue leisure suit over the yellow, big-collared button-front shirt. When that nightmare finally ended, towards the end of the 1970s, the era of fast-fashion had already begun, garment manufacturers chasing the dirt-cheapest seamstresses globally, with cotton falling in price.

Sadly, paper clothing in the 1960s was, in a sense, a harbinger of today’s fast fashion, preparing the world for a new way of consuming as it came off a World War II era of frugality. “Paper clothing introduced the idea of disposability on the larger level, the idea that you can wear something a couple of times and throw it away,” said Hill. “Now you can do this with actual fabric.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]It was inexpensive originally and that was fun. But then it went up in price because big name designers would add one dress to their lineup and make it 75 to 150 dollars—back then!—and how many people can afford that?[/quote]

We can’t totally put the fast-fashion genie back in the bottle. Appetites have been created. Let’s say you just lost 15 pounds for your reunion and you want to show off your new sleekness. Paper clothes could offer some key fill-in fashion options that make an entirely different fashion and clothing manufacturing and delivery system possible.

Perhaps the best argument for the widespread adoption of paper clothing is that it allows the wearer to be true to him or herself. Why be a cog in a cycle of ecological destruction via cotton and shipping container? Seductively tearing a tissue paper garment off your significant other as if the body is a gift is a more dignified way to end things.

This is an argument for embracing the practical. We have the technology. Paper is practical. Let’s roll.

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

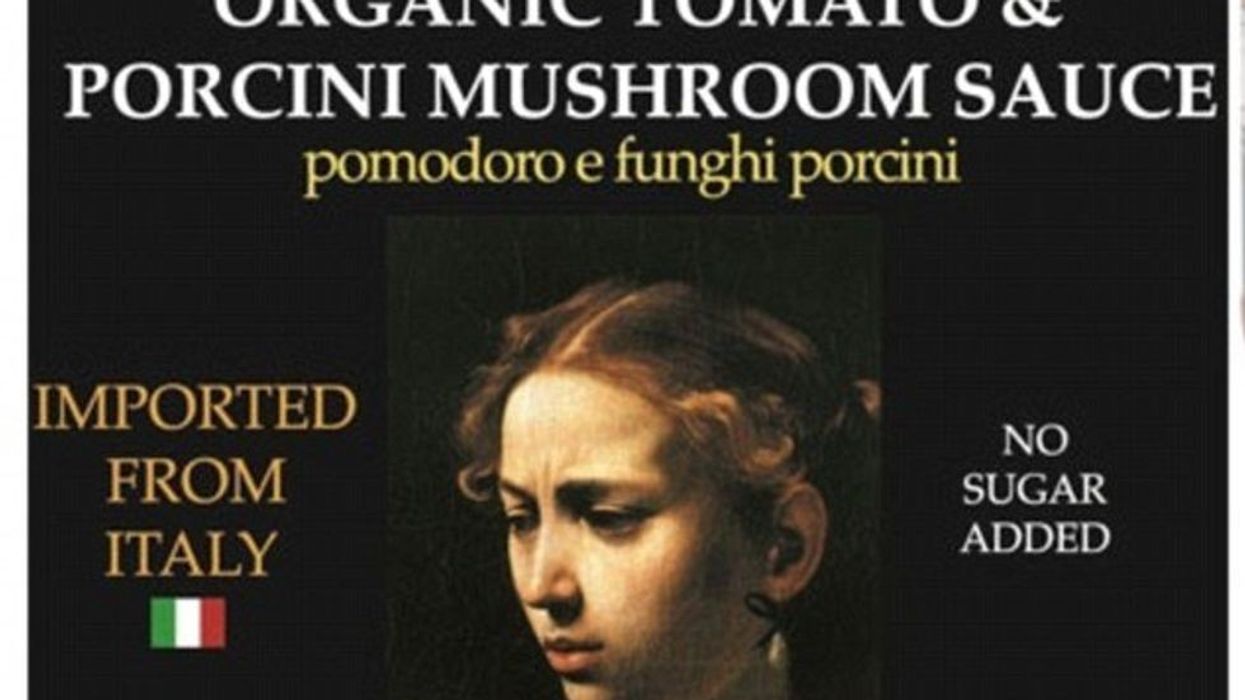

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)