Ekene Ijeoma refers to his cozy, fourth-floor studio in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, as “The Treehouse.” Green metallic vines cover one wall, making me feel as though we’ve secluded ourselves in some kind of futuristic canopy. At first blush, the 31-year-old designer strikes me as laconic, though a playful sense of humor slowly begins to emerge. We joke about how no one uses the option to donate to charity while checking out at Rite Aid, before he wonders aloud, how do we get people to do good?

As an artist and designer, Ijeoma is a unicorn—a sought-after rarity, utilizing a multitude of mediums, like interactive media and installations, and tools, like code and data, with ease. He is careful to note though that these decisions are always made depending on what best serves the concept. And while Ijeoma has worked on commercial projects, his talents and passions converge in his socially conscious work. One piece, The Refugee Project, is a collaboration with design studio Hyperakt that aims to increase awareness of the ongoing refugee crisis. He shows me a now-famous photo of a Turkish police officer carrying a drowned Syrian refugee boy from the beach—a heart-wrenching image that drew international ire. “I was thinking about how much empathy this image created for the issue. How could data visualization do the same thing?”

What emerged was a map that traced global refugee migration since 1975, noting how destinations changed over time and including personal stories to “see the refugee crisis through the eyes of the refugees themselves.” The project is being exhibited in Design Museum’s Designs of the Year and was published in MoMa’s Design and Violence, a digital experiment exploring societal brutality.

“I see design as a way of understanding these issues in a way that you can’t from news,” Ijeoma tells me. “It brings it to a different space.”

Another project, Wage Islands, was inspired by fast food workers’ fight for a higher minimum wage and New York magazine’s historic Hurricane Sandy cover, which showed the city blanketed in darkness. Ijeoma wanted to illustrate the “haves and have-nots” of New York City using two metrics, wages and housing inequality, to explore what he calls a “geography of access.” If the city’s minimum wage were to increase from the $8.75 minimum an hour to $15, how would accessibility change?

[/vimeo]

The result is an interactive, 3D physical model that depicts the relationship between income and geography. Made of over 500 pieces of laser-cut acrylic, the model rises and falls in a dark pool of water according to the wage selected on an attached control. The above-water peaks of the island represent where an individual can afford to live on that particular wage, while what remains submerged is unattainable. As the wage increases, so does the space above the water. At $8.75 an hour, the model begins almost completely immersed. “It was, for me, a poetic way of looking at the issue,” says Ijeoma.

Throughout our conversation, Ijeoma keeps returning to the idea of humanizing data—finding the faces behind the big numbers. “With data, you can tell whatever story you want. Someone asked me once, ‘When you’re working with data like this, isn’t there a risk of telling lies?’” He considers this for a moment. “In the scientific process, you’re trying to answer questions using facts. But in my artistic process, I’m mostly asking questions to inter- rogate facts and reveal broader perspectives of issues that narrower media doesn’t.”

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

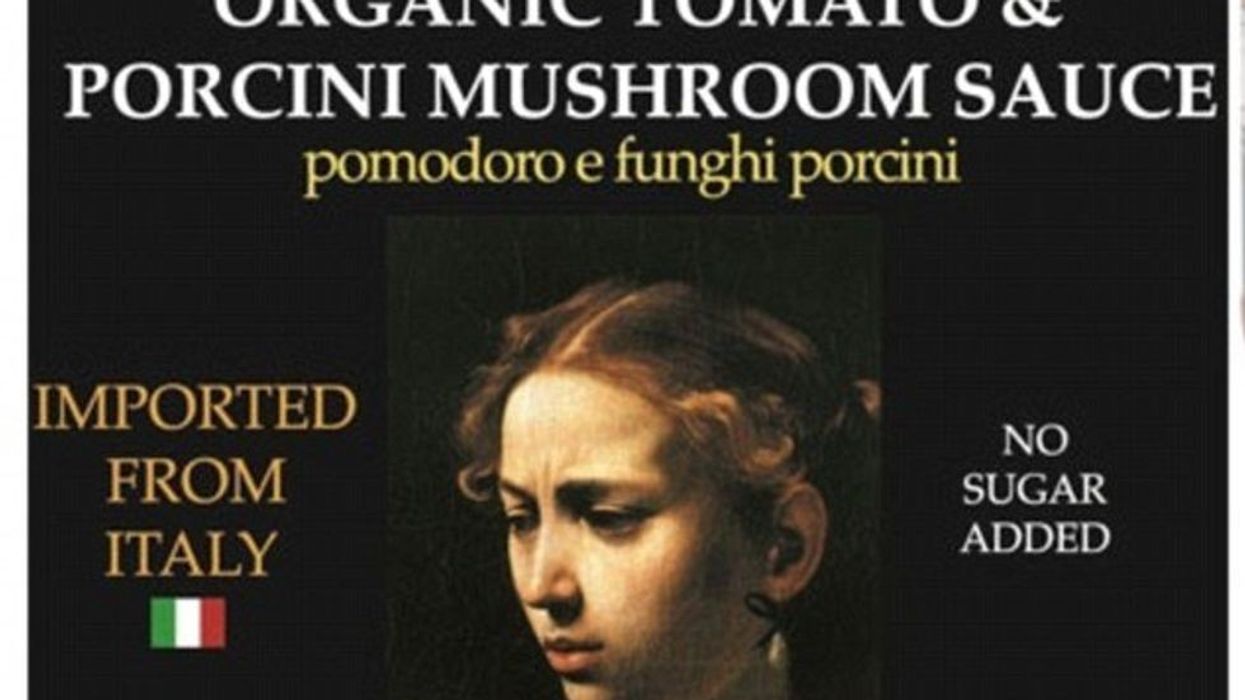

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)