The Wave. For people like me who might be fuzzy on a sport’s technical aspects, it’s one of the best parts of watching a live event. It engages you with the moment like nothing else can and drives up enthusiasm for the action at hand. To see a crowd collaborate in rhythm seems to defy the odds of what most uncoordinated humans are capable of.

The Wave, as intrinsic as it might seem to any bleacher-bound audience today, is a fairly modern invention. The first recorded instance took place on October 15, 1981, at an Oakland A’s baseball game against the New York Yankees. During this historic playoff game, professional cheerleader Krazy George Henderson led the first nationally televised demonstration of The Wave. Soon after, sports fans at a University of Washington in Seattle football game repeated the stunt with the help of retired cheerleader Robb Weller, setting in motion the sporting event ritual that would take the world by storm.

And because The Wave has altered sports history for the better (or for the worse, if you’re not into that brand of rah-rah fervor), Hungarian biological physicist Illés Farkas put a lot of effort into figuring out how it works from a scientific perspective. In a 2002 study published in Nature, Farkas analyzed the collaborative behavior of crowds to better understand how social phenomena resemble microscopic particle behavior. Also, to give you a little background, he refers to The Wave as the Mexican Wave since it gained global fame following a particularly memorable demonstration at the 1986 World Cup in Mexico City.

To arrive at the results, Farkas and his team analyzed 14 waves in a football stadium that housed more than 50,000 people. One section of the study breaks down the physical components well, explaining how much inertia it takes to launch a stadium-wide human wave. Mental Floss was thoughtful enough to convert meters into feet for us Yankees as well:

“The wave usually rolls in a clockwise direction and typically moves at a speed of about [39 feet] (or 20 seats) per second and has a width of about [19 to 39 feet] (corresponding to an average width of 15 seats). It is generated by no more than a few dozen people standing up simultaneously, and subsequently expands through the entire crowd as it acquires a stable, near-linear shape.”

Essentially, if you suddenly feel the urge to start a wave of your own, plan on convincing at least a dozen people to back you up. Otherwise, be comfortable with suffering an embarrassment as minimal as a failed slow clap. So, if you’re going to be at a sporting even on this fine Saturday, I encourage you to take that risk in honor of The Wave’s 35th birthday. Its survival rests in our upraised hands.

A road near equatorial Atlantic OceanCanva

A road near equatorial Atlantic OceanCanva Waves crash against rocksCanva

Waves crash against rocksCanva

Two people study a mapCanva

Two people study a mapCanva Foggy Chinese villageCanva

Foggy Chinese villageCanva

Older woman drinking coffee and looking out the window.Photo credit:

Older woman drinking coffee and looking out the window.Photo credit:  An older woman meditates in a park.Photo credit:

An older woman meditates in a park.Photo credit:  Father and Daughter pose for a family picture.Photo credit:

Father and Daughter pose for a family picture.Photo credit:  Woman receives a vaccine shot.Photo credit:

Woman receives a vaccine shot.Photo credit:

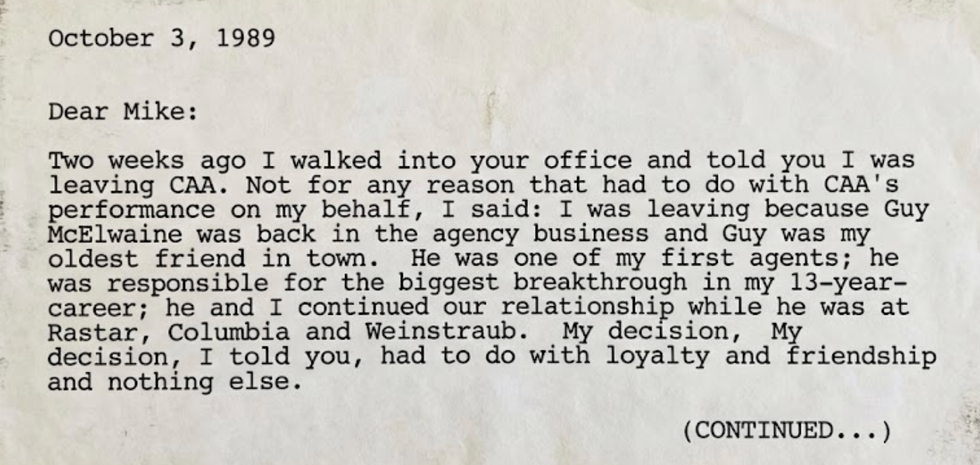

An excerpt of the faxCanva

An excerpt of the faxCanva

Robert Redford advocating against the demolition of Santa Monica Pier while filming "The Sting" 1973

Robert Redford advocating against the demolition of Santa Monica Pier while filming "The Sting" 1973