“Just keep your hand inside the car, if you’re going to take video out the window,” SportUp Executive Director Stephen Minix advises me, as we’re on our way to visit the Watts Towers.

“Why?” I ask.

“You’re holding an object in your hand out the window of a car—people won’t like that.”

Oh.

Whoa.

When you’re driving through Los Angeles, it can sometimes be difficult to know your circumstances. After all, much of it is 1950’s ranch-house sprawl baking in the Southern California sun—many of the neighborhoods look just like anywhere else in town. But the details are different. And that’s what shapes the experience of those who live there.

The Watts Bears were a program that caught my eye from the moment I began working with the SportUp team. Their story, which has never been more timely, shows the power of sports to unite a community—the influence of this youth football program reaches far beyond the field. And it’s a story that we, as a society, have perhaps never needed more so than we do now.

The video above is a mini-documentary on the Bears, shot over three days with the program in mid-September, in the latter stages of their fall season. It was the result of a trip to visit the program and their training site, Locke High School in South Los Angeles—a site at the epicenter of gang activity in LA for decades.

However, tapping into the momentum of change at Locke High School, brought on in part by Minix himself, the Watts Bears are a strong, unifying factor in a complex social and urban landscape.

Part of an outreach program through the Los Angeles Police Department’s Southeast Community Police Station, the Bears’ coaches and general manager—all LAPD officers—know those details quite well.

And that knowledge, along with a work ethic and commitment to their players that extends to visiting their schools, checking in with teachers, and running summer academic and track programs, is revolutionizing the way a generation views and interacts with law enforcement.

The program is free. The only requirements for the athletes are that they attend school and work to be good students, and treat their teachers, parents, coaches, teammates, and peers with respect.

Through sport, they form bonds of commitment and friendship that crisscross neighborhoods and tie new groups together. While at first there was some discomfort about police officers running the program, now there is a greater sense of safety. And while once there was only one team of roughly 20 athletes, now there are three teams, with more than 80 Bears taking the field each weekend as the summer draws to a close in LA.

Watts has faced a tremendous number of challenges

“East LA—another area that is looked at as a difficult place to live—is an area that immigrants from Mexico and Central and South America saw as a desirable destination,” Minix says. “They did everything they could to get there, and when they got there, they’d made it—they took care of it because they’d made it now.

“Whereas here, this is more like a place where you’re deposited, or where you wind up when you don’t have options. This is the only place where you can find cheap housing, or housing projects—there are no libraries, there’s nothing positive around here on a scale that any normal neighborhood would need to help young kids.”

As we’re driving, we pass by an educational center.

“Look,” Minix says. “There’s one. But, can you get in?”

It’s a rhetorical question, since it’s surrounded by an 10-foot tall iron fence.

“Everything is covered in razor-wire. Few people value this area, and the ones that do are all 50 and above,” he says. “They’ve been here so long that they remember when this was a place that would inspire Simon Rodia to build the Watts Towers.”

It was also once home to the automobile industry, as evidenced by the abundance of now-dilapidated warehouses. Like Detroit, nothing came to fill the void left by the waning auto industry—soon, many people were without jobs or prospects.

“There’s no opportunity. There’s no enrichment. There are no parks. Just keep making a list—have you seen anything here, outside of the personality of the people and the Watts Towers, where you’ve said, hey, that’s pretty cool?”

Things have begun to change, however, with Locke’s revolution. Once the high school started to turn the corner, it became a new focal point for the neighborhood—but that can also be a cross to bear.

“Locke became the center of everything. You have to be the teachers, the community builders, the disciplinarians, the social hub, the alumni coordinators—and that’s hard. It’s not something that a lot of the teachers coming in here are ready to deal with—they’re showing up thinking that they’re going to be teaching math.”

This is something that still applies—the area’s several schools are the lone islands of community activity and engagement, with little other civic infrastructure to reach the adult population.

He adds: “It’s easy to focus on all the challenges, but it’s still a really good place. There are so many good people here. It’s still an awesome spot.”

Rewriting history

“Those are busy days for us,” explains Officer Holliman, one of the Bears’ coaches, talking about the school visits that the Bears staff build into their schedule.

“We’ll come in at 11 a.m., put our uniforms on, and head to whatever schools we’ve lined up for that day—we’ve got about 80 kids on our team. We’d love to have all their schools checked by Christmas break,” Holliman says.

It’s a powerful way to connect with the community, and to reinforce the values that they’re teaching on the field.

“We’ll show up at the school, meet with the principal, tell them about our program and explain that there are kids at their school who are on the team. Usually, they love it.”

The officer-coaches will then visit the classroom, spend some time observing, meet with the teacher and their student-athlete, and establish a relationship, which will pay dividends for both the child and the teacher in the long run. “That’s where the mentoring part of our program comes in,” he says.

“We’re providing them with what would probably be a $500 program for free—instead of asking for $500, we are asking them to apply themselves, in school and at practice.”

The presence of the four officer-coaches on campus makes an impression that lasts, and that immediately communicates to other students.

“We have teachers coming out of their classrooms saying, ‘Officer! Can you talk to my class?’ The school visits can take hours, because if a teacher flags us down, regardless of if they have kids in our program or not, it’s our job to try to help kids if they’re having an issue or problem at school. They might just need a little coaching or mentoring—we try to provide that, and hope to have them join the Watts Bears in the next season. It’s an intervention for these kids.”

There’s a growing sense of positive energy.

Driving through the neighborhood with Minix, I ask him what he feels has changed the most since he first arrived in the area in 2002.

“What I’ve noticed that has changed about Locke and Watts from when I got here is that at least the anger is gone.”

Holliman echoes that sentiment, recalling the days when he and his fellow officers would have to cruise around Locke every afternoon to try to cut down on gang violence.

“It was a daily thing. But the vibe has changed,” Holliman says.

It’s a delicate balance

Over the past decade, some very dedicated people have spent a great deal of time working to make Watts a better place. The Bears are one part of that equation. There is upward momentum, yes, but it’s still in need of a daily push to keep that change alive.

The challenges that these kids, coaches, parents, teachers, and administrators face have not vanished. They have been diminished to some extent, but only by means of the dedication of those who run community programs like the Bears, and the commitment and engagement of the participants and their families. As an outsider, you come away with the impression that tremendous gains have been made—but that there is no time to rest on laurels.

That’s something that the Watts Bears understand.

“It becomes so much more than just football and school,” Holliman says. “When we talk to the kids, we’ll find out things that are going on at home, challenges that neither we, nor their school, might know about, and then we have to figure out how to pool other resources to try to help. Then, it’s not just that well, this kid isn’t paying attention in class—there’s so much more going on that we don’t realize. We know it’s there, but we just don’t know what it is. That’s why the one-on-one time during school visits is so important. And as police officers, we’re lucky in that we have resources—we have access to a lot of different people who can help.”

He continues: “It’s a blessing, but it’s also tough, because there are only four of us. But we don’t back away from that challenge.”

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025.

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025. Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.

Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

A home pregnancy test Canva

A home pregnancy test Canva

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

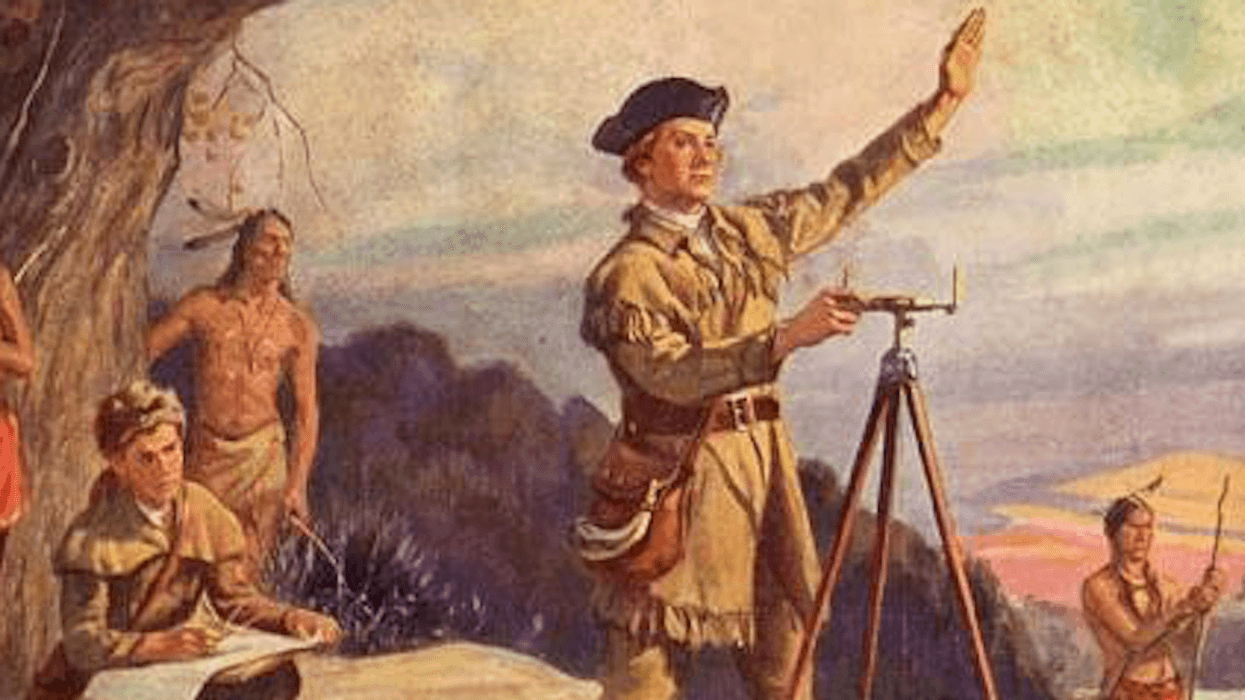

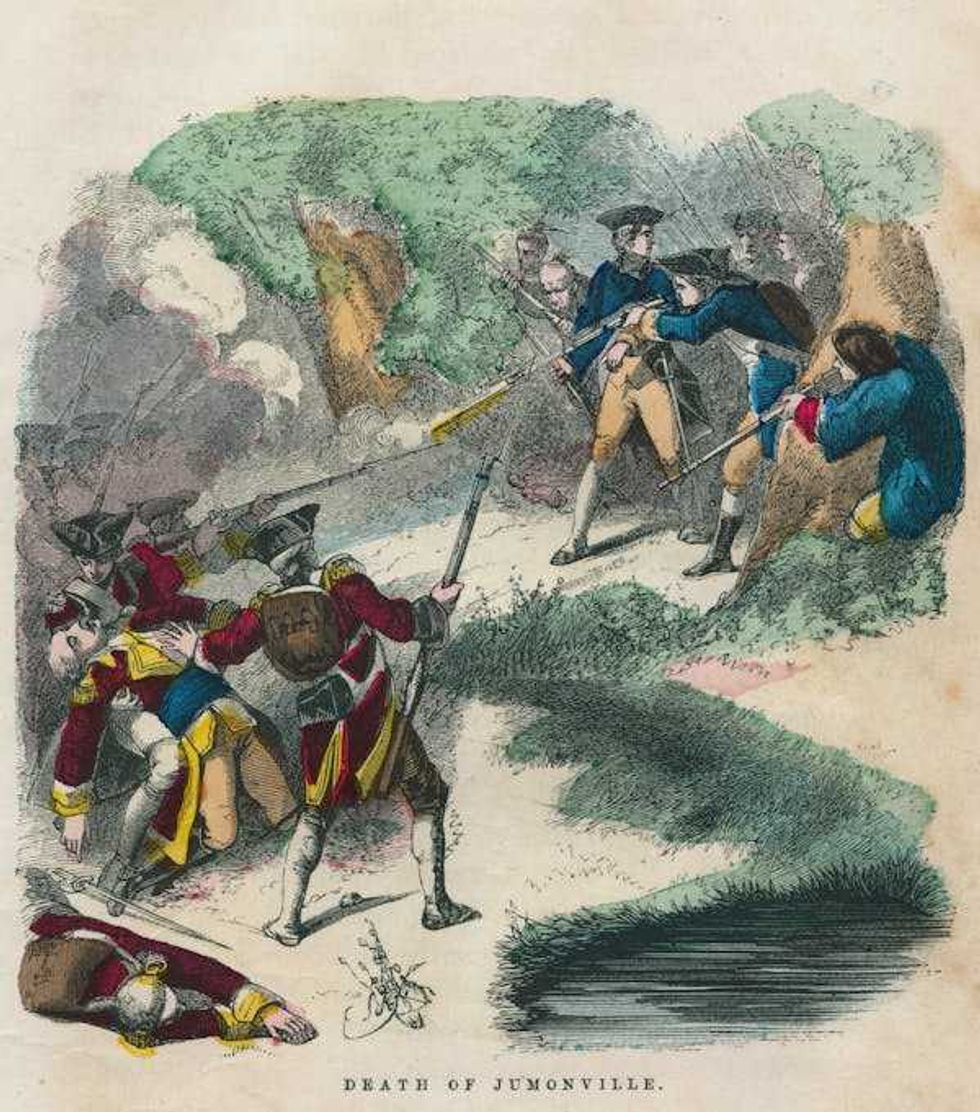

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War.

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War. Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity.

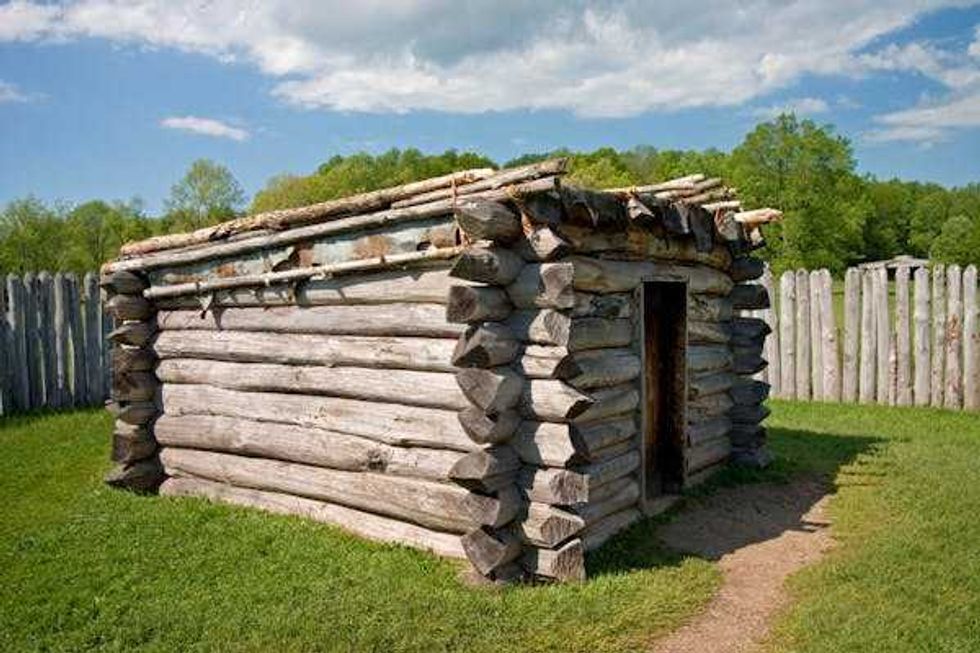

Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity. A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.