Most of my peers didn’t understand the decision I was making, but at the end of my sophomore year of high school, I walked into the principal’s office at my high school to sign my dropout papers. The skepticism in the room was palpable, from both the principal and office staffers I’d come to know over the past year. But my mother was with me, and her mood was far more amiable. “It’s your choice,” she said. And it was, for a lot of complicated reasons that I’d carefully thought through. So I signed my name on the form.

I was leaving Whitney High School, which — then and now — was not only ranked as one of the best high schools in the state of California but as one of the best high schools in the country. The Los Angeles Times called it “a place where ‘fail’ is a four-letter word.” It was, infamously, the subject of Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Edward Humes’ 2003 book “School of Dreams: Making the Grade at a Top American High School.” In the book, Humes painted a portrait of a student body that was rigorously tested and ferociously dedicated to academic life. In the introduction, he wrote:

“Test scores at Whitney rival those at the nation’s most elite private and public academies, the best colleges in the country court and woo the seniors like starstruck autograph seekers, few years go by without someone (or two or three) scoring a perfect SAT. People don’t just move from other cities to this geographically unfashionable L.A. suburb so they can send their kids to Whitney. They move from other countries to attend an American public high school.”

Whitney was indeed a public high school, but you still had to test to get in. My parents had moved to Cerritos, the L.A. County suburb where Whitney was located, specifically for the competitive schools it housed in its district. I spent a year at Cerritos High School and then took the qualifying test to transfer to Whitney. I spent a year there, and though plenty of classmates loved it, I was miserable.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]I became an expert at filling in bubbles and writing five-paragraph essays under an hour.[/quote]

Some people dropout because they have struggles at home or experience bullying. My circumstances were less dramatic: I was just all tested out. We took tests all the time. Practice tests. And practice tests for the practice tests. I became an expert at filling in bubbles and writing five-paragraph essays under an hour. My hand cramped all the time, and I started to resent school, something I used to truly love. Whitney was in competition with another reputable magnet school in neighboring Cypress, California, called Oxford Academy, and our instructors let us know that it depended on us to never fail in order to keep Whitney’s rankings high enough to beat them. But my grades at Whitney rapidly dropped, and studying in this rigid, unimaginative way made me anxious and sad. Whitney’s was a system that worked for many students, but it had burned me out. Though I can’t speak to the school’s methods these days, by the time I entered the administrative office to dropout, I was more than ready to leave.

Here’s a spoiler alert: Everything turned out OK. I went to community college then transferred to a four-year university (University of Southern California, where I accrued a shameful amount of debt — though not quite as shameful as others since I was only there for two years). At orientation, I even ran into some of my former high school friends who were entering university at the same time I was — except I was joining as a junior, and they were freshmen. If there were any mistakes made, it was my decision to major in print journalism and become a writer. Now I work as an associate editor at a National-Magazine-Award-winning publication, but all my credit cards are maxed out and the creditor’s bureau is after for me for an outstanding $35 bill. It’s fine.

So sure, I’m broke — but (mostly) by choice. And I have the same four-year degree that all my peers do as well as the prestigious student loan debt. To become the occasionally productive member of society I am today, I took the California High School Proficiency Exam (CHSPE), a state testing program that basically earned me the equivalent of a high school diploma and allowed me to exit high school early. Competitive four-year universities don’t automatically grant enrollment to people with CHSPE-earned certificates, but anyone is welcome to take the exam, go to a two-year school, and transfer to a university, same as everybody else. It was a gamble, but I was sure I could do it. By California law, any institutions that require a high school diploma are required to treat the CHSPE certificate like it is one.

I can’t recommend my path to everyone. (Seriously: For many people, dropping out results in “negative employment and life outcomes.”) But if you’ve carefully weighed your options and believe my life hack might set you up to achieve success, there’s more than one merit to the strategy. First, you’ll save a ton of money by going to a two-year community college to acquire a big chunk of your required credits. Second, you can completely avoid those awful SAT and ACT tests because four-year universities don’t require them from transfer students. If you do well enough at community college to earn an associate’s degree, your acceptance into most four-year colleges is all but certain — many community colleges offer transfer tracks, which means you’re guaranteed admission to certain schools if you just earn the required credits with acceptable grades. No tests required.

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]My dropout strategy is not a one-size-fits-all approach.[/quote]

I’ll say it again: My dropout strategy is not a one-size-fits-all approach. More than a few things were working in my favor: Despite my poor test-taking skills, I was a really good student when a subject engaged me (and in college, most subjects did). I come from a middle-class family that was happy to support me when needed throughout my college education. I flourished in a university environment where the emphasis was less on testing and the rote memorization of facts and more about demonstrating a full understanding of concepts and processes. I’m charming, so my professors loved me. Besides, I was also the only 16-year-old in all my classes, which made me a welcome novelty in all my study groups.

Today, student loan debt is really high, and a high school diploma — and a college degree — isn’t an automatic ticket to success. The notion of the traditional 40-hour-a-week gig is losing out more often to entrepreneurship and freelance work. I found a way to honestly assess my skills and weaknesses and made my own educational path work for me. I’m not saying you, too, should dropout, but that you should figure out what works for you. (And if you’re lucky enough to have a mom like mine, ask her to come with you to sign any requisite forms. Seriously, it helps.)

A collection of toilet paper rollsCanva

A collection of toilet paper rollsCanva A bidet next to a toiletCanva

A bidet next to a toiletCanva A cute pig looks at the cameraCanva

A cute pig looks at the cameraCanva A gif of Bill Murray at the dentist via

A gif of Bill Murray at the dentist via  A woman scrolls on her phoneCanva

A woman scrolls on her phoneCanva

A confident woman gives a speech in front of a large crowdCanva

A confident woman gives a speech in front of a large crowdCanva

The 'weird' car ceiling handle above the windowCanva

The 'weird' car ceiling handle above the windowCanva A gif of a dog and cat screaming in a car via

A gif of a dog and cat screaming in a car via

Creativity and innovation are both likely to become increasingly important for young people entering the workplace, especially as AI continues to grow.

Creativity and innovation are both likely to become increasingly important for young people entering the workplace, especially as AI continues to grow.

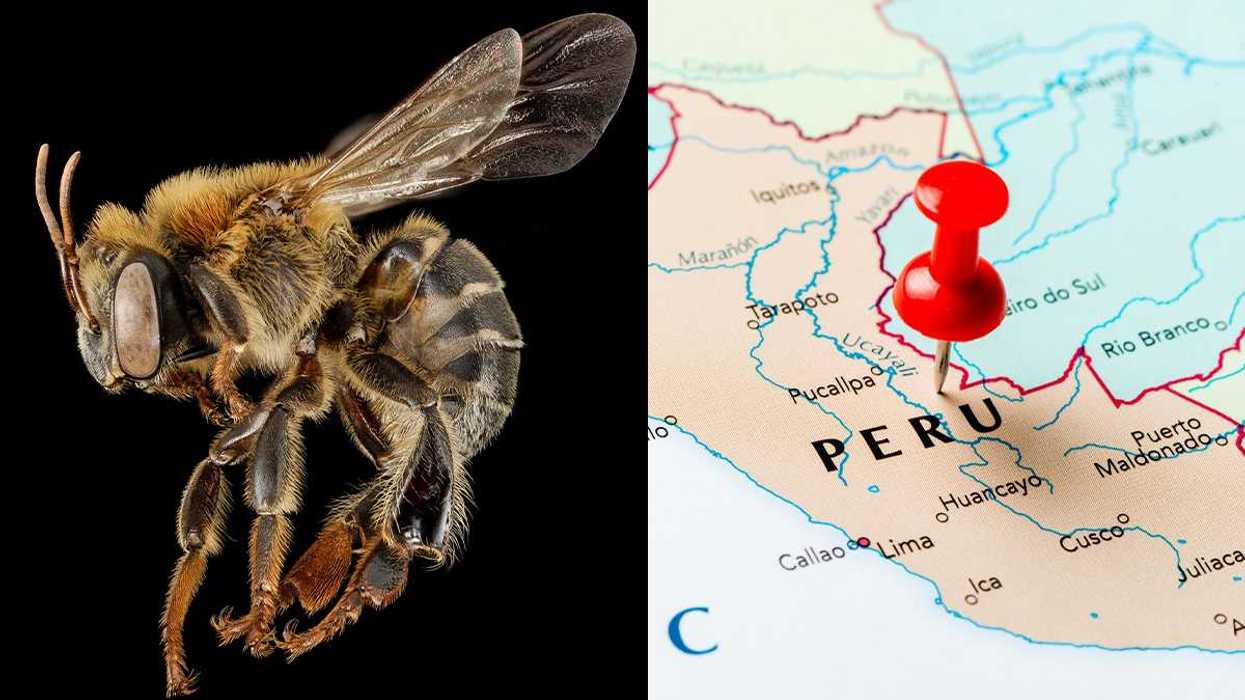

Peru stingless bee.USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab/

Peru stingless bee.USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab/  Indigenous Peruvian people.Photo credit

Indigenous Peruvian people.Photo credit