For many students, playing games in schools was a blessing and a curse. They were a blessing because videogames such as Math Blaster, the mid-80s title I grew up on, was a welcome reprieve from schooling. These games were also a boon for teachers, who were able to add a fun, interactive tool to their lesson plans. It was a valiant effort on the part of educators, but there was one problem: The games sucked.

Compare a standard educational game title to, say, the lush, seductive graphics of the newly-released Destiny or even the open-ended and infinite simplicity of Minecraft, edugames have a hard time competing. “You can’t fool the kids,” says Joel Klein, CEO of Amplify, the education startup housed with the media giant News Corp. “They want world-class game designers.”

Klein would know a thing or two about what students want. He served as chancellor of the New York City Department of Education, where he oversaw a system of more than a million students. That’s more kids than the entire population of San Francisco. And games are a natural fit for a company that’s focused on the next generation of digital kids. “Great games have the capacity to keep kids engaged in intense, high-cognitive tasks for long periods of time,” says Amplify Learning’s vice president of games, Justin Leites.

So it’s no surprise that this week, Amplify is giving kids what they want with the math puzzler Twelve. Designed by London’s Bossa Studios, the same folks behind the madcap hit Surgeon Simulator, Twelve is a devilishly difficult platforming game (a la Super Mario Brothers) that actually uses math as a novel play mechanic, rather than a tone-deaf attempt to trick kids into learning. In Twelve, you play as a lost and lonely number trying to find “the one.” You must avoid zombies (the number zero, obviously) while employing algebraic equations to traverse the dark and brooding world.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]In the past, educators would simply impose education over a game like covering broccoli in chocolate.[/quote]

Although hiring phenomenal game designers to make good educational games would seem like an obvious approach, Bossa’s background as commercial game-makers is anomalous in the world of edugames. In other media, the interest of talented creators has been a boon. Jim Henson famously used his background in advertising to fuel the stickiness of Sesame Street’s vignettes, and Davis Guggenheim’s directorial talents from Deadwood carried over to the documentaries Waiting for Superman and An Inconvenient Truth.

But games have not seen the same type of top talent move over into the educational and learning spaces. Leites says that hiring better game designers is central to their strategy. “The games can’t be homework,” he says. “In the past, educators would simply impose education over a game like covering broccoli in chocolate.” Given that the Pew Research Internet Project found that 97 percent of American teens play video games and smash hits like Minecraft dominate screen time, educators hoping to use games are facing stiff competition. “Kids will know: ‘You’re trying to get me to do math problems!’” Leites jokes.

To pull together the right talent, Leites spent months traveling through the United States and Europe, visiting studios and talking to game designers. Amplify tapped Rob Auten and Tom Bissell, the writing duo behind the latest Gears of War, and brought in game designer Jesse Schell to create Lexica, a massive role-playing game that encourages kids to read classics like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. To create new titles, Amplify even pulled folks such as Matthue Roth, author of the children’s book My First Kafka, from outside the gaming world.

Educational games are often underfunded and given that the design work is often performed by amateurs, Leites says. Moreover, the critical process of failure and iteration that makes good games great is rarely executed. “On a good day, one in 10 ideas work,” Leites says, citing the philosophy of well-respected and influential Ultima Online designer Raph Koster. It’s a process Leites understands well, as he once worked as a play-tester for New York City board game company SPI. “Those games tended to be more cerebral than, say, a first-person shooter,” Leites says.

One of the biggest things Leites learned from the experience was that game designers would be more motivated to create good work if they chose their own subject matter. That creative decision was on full display with Twelve. After connecting through a friend of a friend, Leites brought Imre Jele, co-founder of Bossa Studios, to Amplify’s DUMBO offices in Brooklyn to discuss working on a new title. “Making an educational game was going to be a challenge,” Jele says. And given Bossa’s previous work on the popular Surgeon Simulator, a bizarre game that places you as an amateur surgeon, the Shoreditch-housed studio might have seemed like a strange pick to create games for children.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Kids don’t hate math… They hate math class.[/quote]

But Imre, who learned English from the Monty Python films, saw an opportunity to blend two of his favorite subjects—comedy and math—into a single experience. “Kids don’t hate math,” Jele says. “They hate math class.” Twelve feels nothing like math class and showcases a marvelous blend of puzzles with actual algebraic problem-solving. “We just want to present you with a universe,” Jele says.

The long-term hope is that one of Amplify’s games becomes a hit. Early on, titles such as The Oregon Trail and Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? pointed to a potential future where good game design could sit alongside commercial success. Amplify hopes its taste-making and talent-tapping is part of the key to creating engaging games that kids can play alongside something like Minecraft. “We want kids to spend the time with our games, but they won’t do that if they’re boring,” Klein says.

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

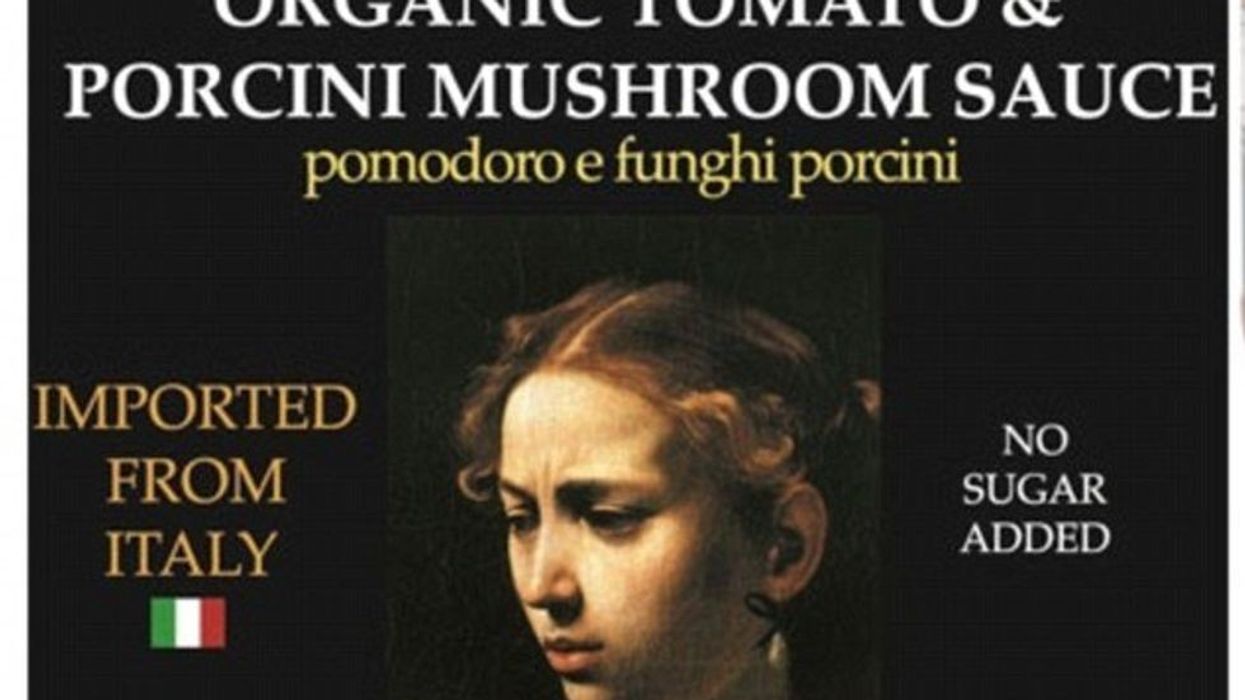

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)