It’s a gray Sunday morning in London’s trendy Shoreditch district, and street artist eL Seed has inadvertently found himself working a nine-to-five job.

These certainly aren’t normal hours for the renowned French-Tunisian creative, whose work graces walls, bridges, rooftops, and other structures and surfaces on nearly every continent. Though eL Seed normally splits his time between Paris and Dubai, he’s in London to paint a large mural commissioned by the British Council for the Shubbak festival, a celebration of contemporary Arab culture. The production team is pacing nervously, worried he won’t finish by his deadline.

There are other complications, too: Storm clouds are hanging low in the sky, eL Seed has a flight out of Heathrow Airport in less than 24 hours, and he couldn’t work through the previous evening as he usually does, due to a queue for the nightclub below crowding his workspace.

“I usually don’t work like this, within these strict hours,” he says with a resigned smile. “But if it rains, I’ll just wear a plastic bag and get it done somehow.”

This tireless work ethic has taken eL Seed far. Combining Arabic calligraphy with graffiti—spawning his hybrid “calligraffiti” style—he has gained international acclaim and painted everywhere from Paris’ famous Pont des Arts bridge to disenfranchised townships in South Africa. Through a mixture of commissioned work and self-funded creative projects, he taps into being a “third culture kid”—growing up in suburban Paris, he spoke French to his parents, who replied to him in Arabic—to inform his work. While he began painting at a young age, he only learned to properly read and write Arabic when he was 18. As a calligrapher he is entirely self-taught, which is largely unheard of in the ancient Arab tradition.

“My art is just the projection of what I am. I wouldn’t be doing what I do if I was just born in Tunisia,” eL Seed says frankly. “In France, they make you feel like you can only be French, but in my case—my face doesn’t look French, my name doesn’t sound French—you have this crisis of identity. That’s what prompted me to learn Arabic, to get back to my roots.”

The British production manager uneasily tracking eL Seed’s progress on this Sunday morning turns away journalists scheduled to interview him (including me), claiming it would be detrimental to interrupt his creative process. The artist, he firmly insists, is at work. But eL Seed, ever gracious, rebuffs the idea that I’m hindering his progress. “Please come back,” he writes apologetically via a WhatsApp message a few minutes later. “He is not the one who gets to decide that.”

Despite his renowned reputation, there is a palpable humility to eL Seed evident not only in his demeanor and impeccable manners, but also in his work. He doesn’t sign his pieces—“as soon as I leave, the wall’s not mine anymore”—and firmly rejects the media’s tendency to depict him as being instrumental in the 2011 Tunisian revolution, which sparked the Arab Spring.

“I’ve read articles creating this fake romance around me saying ‘eL Seed, the painter of the revolution,’” he says, rolling his eyes at the notion. “I was not there. People died for that, and I was not a hero in Tunisia, so I don’t want to be portrayed as that. I had painted in Tunisia before the revolution, but I didn’t for a while afterwards because, for me, it was too opportunistic.”

Though eL Seed’s work is tied to a strong sense of Islamic and Arab identity, which he describes using words like “deep, rich, and intense,” it manages to transcend the language and the region that it’s from.

Removing thick black latex gloves to scroll through his phone, eL Seed pulls up a music video of a famous Brazilian musician performing atop one of his pieces in the favela of Vidigal in Rio de Janeiro. He says that when he painted a Brazilian poem translated into Arabic on the white rooftop without permission, he had no idea what the response would be.

“I came home, and had a bunch of notifications on my phone, and one Brazilian photographer saying, ‘This morning when I came to the favela, I found this beautiful piece made by an unidentified artist. Thank you for beautifying my building.’ Turns out it was actually an art school that he was building in the favela.”

Whether eL Seed’s pieces are adorning a favela or London’s hippest neighborhood, there are four elements to each of his works. The first are the words, which he puts a lot of thought into and are very location-specific. For the mural in London, it’s a quote from John Locke: “It is one thing to show a man that he is in error and another to put him in possession of the truth.” The second is the visual scale, composition, and beauty of the piece, which anyone can appreciate whether they speak Arabic or not. The third is the artwork’s placement—his choice to display it in a small town in Tunisia, for example, rather than in a gallery in Manhattan—which allows it to be simultaneously democratic, accessible, and ephemeral. The last step is the work’s journey through social media channels, as people all over the world can not only see and share his work, but join in on the experience of translating and contemplating the literal meaning of the piece.

When these four layers of eL Seed’s work coalesce, they invite viewers to connect to a culture that, given today’s headlines, is as often misunderstood as it is marginalized. In that sense, eL Seed isn’t just creating art—he is offering an alternative entry point into the culture and belief system that is central to his identity. Ever humble, he says the intrinsic allure of the ancient tradition of calligraphy does a lot of that work for him.

“I feel like there is a kind of universal beauty in the Arabic script that reaches your soul before it touches your eyes,” he says. “People come here, they don’t even know what is written, but they know that this is Arabic because of the shape of the letter and so they can appreciate it and connect to it.”

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

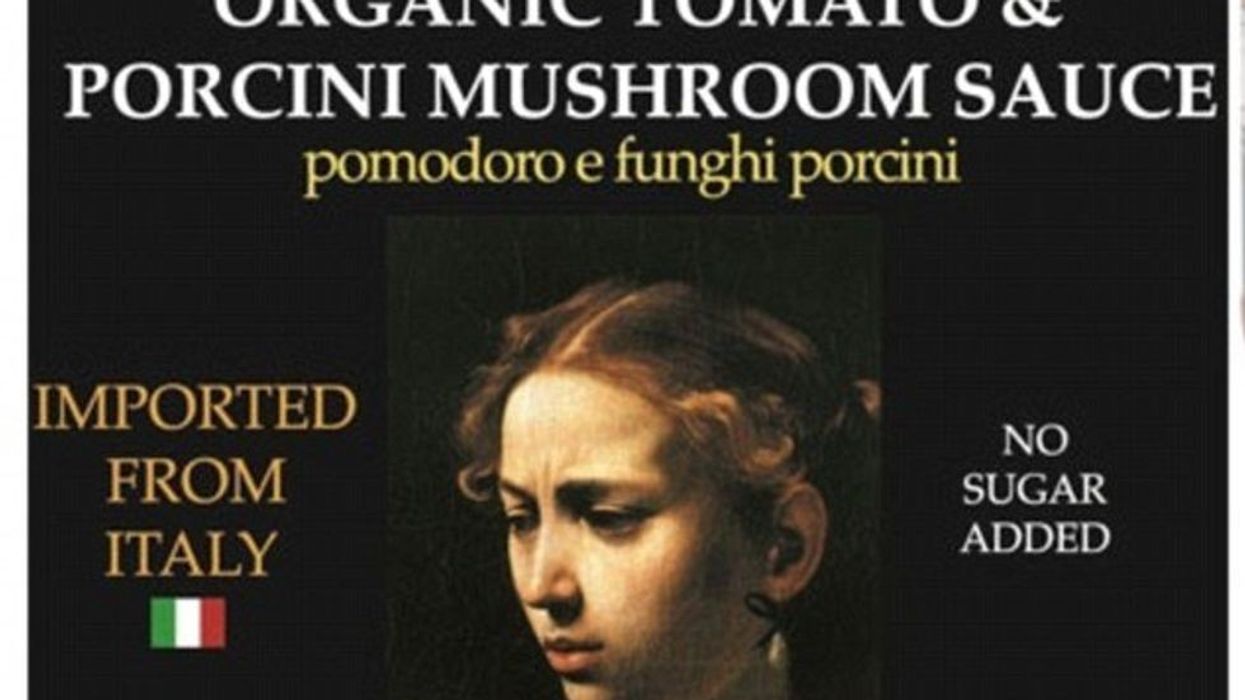

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)