Lina Sergie Attar is a Syrian writer, aid worker, and architect based in Illinois. She started Karam Foundation in 2007 to aid displaced Syrians in need, offering everything from food and healthcare to education and leadership courses. At two of Karam’s schools in Reyhanli, Turkey, just over the Syrian border, Attar hosts Zeitouna, an annual creative therapy and wellness program designed for Syrian children that uses art and self-expression to counter the impact of trauma.

One of the program’s mentors is American artist and writer Molly Crabapple, who in recent years has aimed her ink pens at political and cultural upheaval. Reporting from the Bab al-Salam refugee camp in northern Syria, the rubble of Gaza’s Shuja’iyya neighborhood, and Eric Garner’s memorial in Staten Island, she uses frantic lines, color splotching, and vignetted frames to turn intimate moments of struggle into surreal graphic vérité. Her recent memoir, Drawing Blood, chronicles her journey from struggling art student in New York to renegade activist journalist.

The pair first connected in 2014 when Crabapple contributed art to the #100000Names awareness campaign, which concluded with a public reading in front of the White House of the names of 100,000 fallen Syrians. For the past two years, Crabapple has painted murals for Zeitouna at Al Salam School and Jeel School in Reyhanli. The friends reconnected to reflect on Western distortion of the Syrian narrative and the importance of self-representation.

Lina Sergie Attar: Last year, for our leadership program for Syrian refugee teens in southern Turkey, we built them a computer lab and prepared courses in coding, entrepreneurship, technology, chess, sports, and art. We had a journalist with us, Hala Droubi, and the kids kept asking her, “Who are you? What do you do?” When she told them she was a journalist, they asked her to teach them.

As somebody who grew up in Syria, that’s very foreign to me. Journalism was not a space that people aspired to work in. There was no freedom of speech. It took very courageous journalists—most of whom ended up in prison—to do any honest and truthful writing. But this generation of Syrians, they’re very different. They’re watching themselves grow up on YouTube, watching stories of their country on the news. I think journalism appeals to them because, now, they can tell their own stories.

Molly Crabapple: Syria is perhaps one of the most recorded, portrayed conflicts in the world, and yet, in English-language media, there’s a real dearth of Syrian voices. It’s so important that Syrians are speaking for themselves as opposed to having a lens put on them by Westerners.

LSA: It’s very hard for me to speak about refugees to American audiences. First of all, there aren’t many Syrian refugees in America, only around 2,000. The number is minuscule in comparison to all of these stories about Syrian refugees who’ve come here, but [the media] ignores the millions that weren’t able to come.

Molly, the most powerful thing about your pieces are that you use the lens of your art, but you’re also giving the voice to a Syrian citizen. I’d like for you to talk about that—the merging of art and journalism is something very special in your work.

MC: You’re talking about my collaboration with a young Syrian writer, Marwan Hisham, who I’ve known for some years now. He took surreptitious photos of life around Raqqa on a cell phone. There were these few that weren’t the usual gory-torture-death-porn shots that ISIS is usually portrayed with in the media. It was little kids looking through trash for objects of value to sell, or people waiting in bread lines. They were things that really captured the poverty and shrinking of public space there. They were astounding photos, so I drew from them and Marwan wrote captions.

This past summer, I spent some time in Shuja’iyya, which is the neighborhood the Israelis fought in during Operation Protective Edge when they invaded the Gaza Strip. There were these decimated buildings, and all this twisted, melted rebar from a hospital that Israel had bombed. People were straightening it out to make it into new building material. It looked like snakes—so malignant and coiled. I was so struck by it. One of my favorite pieces I ever did was of these guys straightening the rebar. I try really hard to filter out the inessential in my work to portray the things that I think are the most powerful and true.

LSA: I feel like everything I’ve wanted to say has already been said, especially in terms of my work as a writer. It used to be so immediate, like I would hear any story and say, “People need to know this. People need to know what’s going on in Syria because they don’t, and if they did know, then they would stop it.” That feeling, that urgency to tell stories in real time, as fast as I could, faded as the crisis became a war.

The scariest part about the Syrian narrative is that there’s an active erasure of the beginning, of why this started. ISIS, the refugee crisis, and the political opposition smother the beginning. I don’t want people to forget why it happened. So many people have disappeared, so many people are dead—and many of them were my friends. That part of history will be erased unless we are all working to keep it recorded somewhere. That’s where I feel our work is, in between memory and history.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]I try really hard to filter out the inessential in my work to portray the things that I think are the most powerful and true.[/quote]

MC: It’s so important because the truth is those people, those original revolutionaries, those original protesters aren’t convenient to anyone. They shame the entire world. And so everyone, every side—America, Russia, Assad—everyone wants to forget that they ever existed because they’re a thorn in all of their memories, a reminder of the ways they failed. Preserving their memories is so vital.

LSA: We never had a chance to process it all. We’re always onto the next big thing, the next big crisis, the next big story. Everyone wants to speak for Syrians, to write on their behalf.

Yesterday, my friend was telling me, “I remember when I was in high school, nobody even knew where Syria was on themap.” A lot of times I wish people still didn’t.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

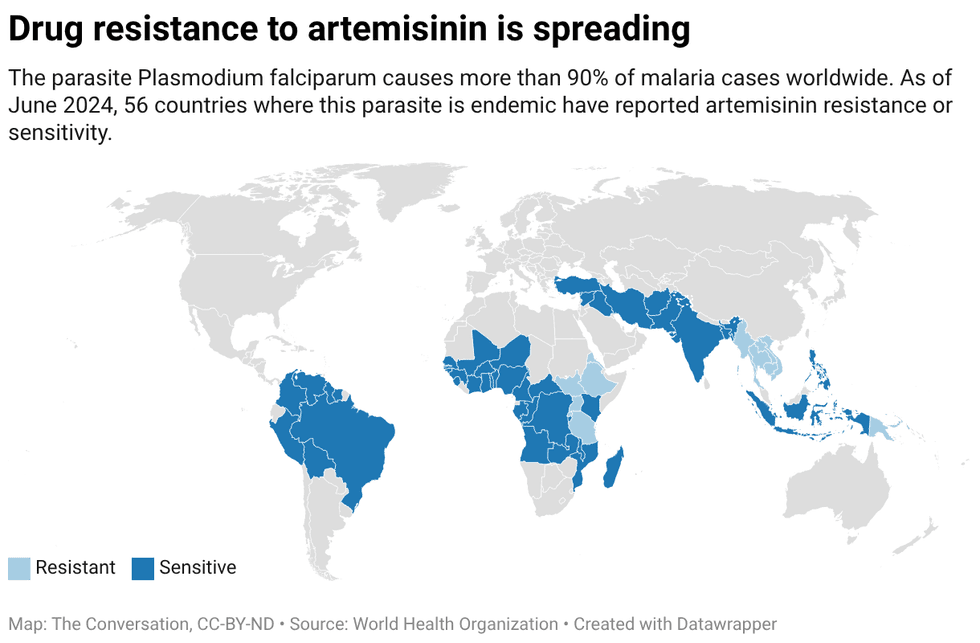

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Created with

Created with  Where to turn off autoplay in your account on Facebook’s website.Screen capture by The Conversation,

Where to turn off autoplay in your account on Facebook’s website.Screen capture by The Conversation,

A young teen cries while listening to music via

A young teen cries while listening to music via

A young couple waits in line at a coffee shopCanva

A young couple waits in line at a coffee shopCanva Gif of Eddie Murphy telling you to think

Gif of Eddie Murphy telling you to think