During one particular late-night editorial meeting, when all of us here at GOOD HQ probably had a few too many, we came up with the idea to send briefs detailing global problems to some of our most creative friends with one simple instruction: to design a solution to the problem in less than 30 minutes, a time frame that would make them think about the problem, but limit the extent to which it might overwhelm them. Call it "The Half-Baked Design Challenge." Some of the solutions are comical. Some are super thoughtful. Some, to be perfectly frank, are mildly disturbing. But all of them engage creatively with a problem in search of a solution, and we think that's a good thing. In this installment, we redesign the single family home.

The single family home conjures a fairly predictable image still—a tree-shaded,slant-roofed, lawn-fronted dwelling standing proudly on its own. You’ve seen kids’ drawings. Chances are you made them yourself many years ago: four little windows facing the street, a windy walkway, and a wisp of smoke rising from a chimney.

It’s a caricature, and, increasingly, a farce—one built on that fabled Jeffersonian foundation of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The true birth of the modern single family home wouldn’t come until May 7, 1947. That’s when William Levitt announced his eponymous housing development in Long Island and 2,000 cookie-cutter houses were claimed within two days. He soon added thousands more—slapped together with record speed, 30 per day. Five other Levittowns sprungup—housing developments with enormous carbon footprints during the golden age of cheap, dirty energy—and suburbia was born.

Levitt’s product found purchase abroad as well—that tangible portion of the American Dream is easily exported. As London, Paris, Toronto, and Tokyo developed in the late 20th century, they too followed the low-density path toward sprawl. One hour outside of Beijing sits Orange County, a development of single family homes designed by a California architect. Announced in 2003, every one of these cartoonish McMansions were snapped up with Levittown-like fervor in less than a month. On the other end of the spectrum is the cautionary tale of lionized architect William McDonough’s Green Village of model homes in Northeast China. The “sustainable” single family homes of Huangbaiyu sit empty—villagers refused to move into them in large part because they simply didn’t accommodate their agrarian way of life.

The urban exodus that built suburbia has reversed globally. As of 2010, more humans live in cities than outside them, and by 2050, 70 percent of us will be urbanites. Clearly, those shifts will not accommodate much growth for the singlefamily home and its resource-squandering design. American millennials are opting out of many of the trappings of the American Dream—they’re driving less, their employment paths are uncertain, and they’re delaying marriage. What then is the most appropriate container for these changing needs? Movement towards co-housing, tiny homes, and the birth of the “micro-unit” apartment building all suggest alternatives—a post-Levitt response in a scaled-back, more shareable economy with diminishing natural resources.

John Steinbeck in his final book Travels With Charley, a ruminating travelogue in search of the American Dream, talked to many who had opted out of that child’s drawing vision of home. He asked one father living with his family in a mobile home how he felt about raising his children without any roots. “What roots are in a housing development of hundreds and thousands of small dwellings almost exactly alike?” the father asked in response. So, let’s take out the crayons and go back to the drawing board.

Ayesha Siddiqi: Writer

Mimicking the relationship between a modern suburban home and the community around it, bedrooms are increasingly furnished as spaces you need to leave as rarely as possible. It’s no surprise that our hyper-individualistic culture treats the bedroom as a shrine for the person living in it—a space to fill with objects that best reflect its resident. But what if bedrooms were nothing more than their name suggests? Just rooms with beds? Forcing all other activity to occur in more commonly shared spaces within the home, and discouraging a selfhood defined through isolated accumulation. Imagine the values such a lifestyle might suggest, the types of habits it would encourage. If kids learned “ours” before they learned “mine.” If the glow of our various screens didn’t follow us where we were meant to sleep.

Pedro Gadanho: Curator, the Museum of Modern Art

The single family home of the future will be a mix of off-the-shelf solutions and DIY creativity, with architects and designers providing improvement apps for your ever-evolving, self-sufficient unit. The units themselves will be parked in urban voids and will grow out of existing buildings like parasites, or be stacked in vertical structures much as the one imagined by architect James Wines back in the 1980s.

Mitchell Joachim: Co-founder, Terreform One

Skywriter Burbs: Extraterritorial Floating Houses Made of Genetically Modified Avian Skeletal Muscle Tissues, 3D Bioprinted Feathers and Impregnated with Helium Gas Flotation Elements.

To rethink the American home is precarious territory—as many have tried it before—but the search for a perfect domicile is not dead. In the last two thousand years, every culture on our planet has attempted to envision the perfect residence. To simply dismiss further inquiry is to give up on a better world. The search for this perfect place is usually labeled as utopian. We must always strive for the impossible or, at the very least, welcome earnest speculation. What is a more perfect home for humankind and our planet? If not a perfect home, what then is a fundamental reboot of its architecture?

Newfangled prototypes of dwellings that are connected to the ever-shifting needs of sustainability are the predominant trend. A decade ago, I proposed a home that would be 100 percent made of living matter or, rather, shaped trees and woody plants, entitled: Fab Tree Hab. A home of living trees is not built, but grown. It is the landscape, not an awkward, foreign addition to the ecosystem. A home made of living arboreal matter would scrub and sequester carbon while producing fresh oxygen—a positive model for our environment.

The next generation of architects is thinking about synthetic biology. Now, the power to control design at the cellular level is an everyday reality. As the costs of doing so continue to decline, the opportunities percolate. Years ago, I planned a home bioengineered with in vitro replication of mammalian pig cells, nicknamed the “meat house.” It is calculated so sentient creatures would not be harmed in the tissue growth of the dwelling. It was essentially a victimless shelter. Recently, a hamburger was announced as being fully fabricated inside a laboratory. Derived from the meaty shoulder of a cow, synthetic biologists custom designed the cells to grow into a tasty burger shape. What can this do for design everywhere?

Similar in technique to the synthetic burger, I grew a house out of cells. Tissue growth of cells into a specific geometry has been possible in regenerative medicine procedures such as bladder transplants. I wanted to illustrate the ecological supremacy achieved by using real organic materials grown from scratch. This is different than, say, using bamboo as a building material and replenishing the harvested supply. Instead, it’s inventing a new material and fully integrating it into nature’s metabolism. It is neither a copy of nature nor the mimicry of nature. It is unsullied nature itself.

Imagine a collection of homes for skywriters. They are not actually professional skywriters per se, but people who circulate in the air each day, sometimes leaving a pixelated contrail. Here is a community comprised of folks who use smart, agile aircraft on a daily basis: flying cars (Terrafugia), jetpacks (Martin Aircraft), dirigibles (Aeros), flying bicycles (XploreAir) and the boundless sport of cluster ballooning (John Ninomiya).

They often choose to leave messages in the form of carbon free dot-matrix clouds. Freedom of speech is their mantra. All day long they can choose to express their concerns in gaseous texts written in air. This activity is intended to scrub carbon monoxide from our atmosphere as they glide to-and-fro.

The men, women, and birds, of the skywriters suburb live in homes made of genetically modified materials. These are extracted from various avian skeletal muscle tissues in the DNA of species like Argentavis magnificens [the Giant Teratorn, the largest flying bird ever discovered]. Birds have benefitted from millions of years of evolution that optimized the weight of their bones and muscle systems. Everything in their bodies is designed for lightweight aeronautical performance. The

same biological tissues that are used in their avian physiology are deployed in the home. Ultimately, each dwelling has an elegant structure of porous and voluminous bird skeletons. In addition, 3D bioprinter factories will produce oblong feathers for insulation elements. With the addition of helium injected into the structure’s membrane walls, the house gently glides across the sky. A series of kite turbines (Makani Power) power the house almost indefinitely. Collections of GM (genetically modified) bird homes float together to form a suburban flock.

Living architecture is a long way from being a mainstream practice. Likewise, the ability to mitigate climate change is of the utmost importance to every architect. Searching for innovative strategies to help solve our current eco-crisis is vital to human survival. New directions in biological design are a magnificent approach to going beyond just survivalist routines. Biodesign is the next step towards a resilient direction where humankind and nature seamlessly blend.

For more fully-baked solutions, check out our companion piece about the future of the single family home.

Illustrations by Kate Bingaman-Burt

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

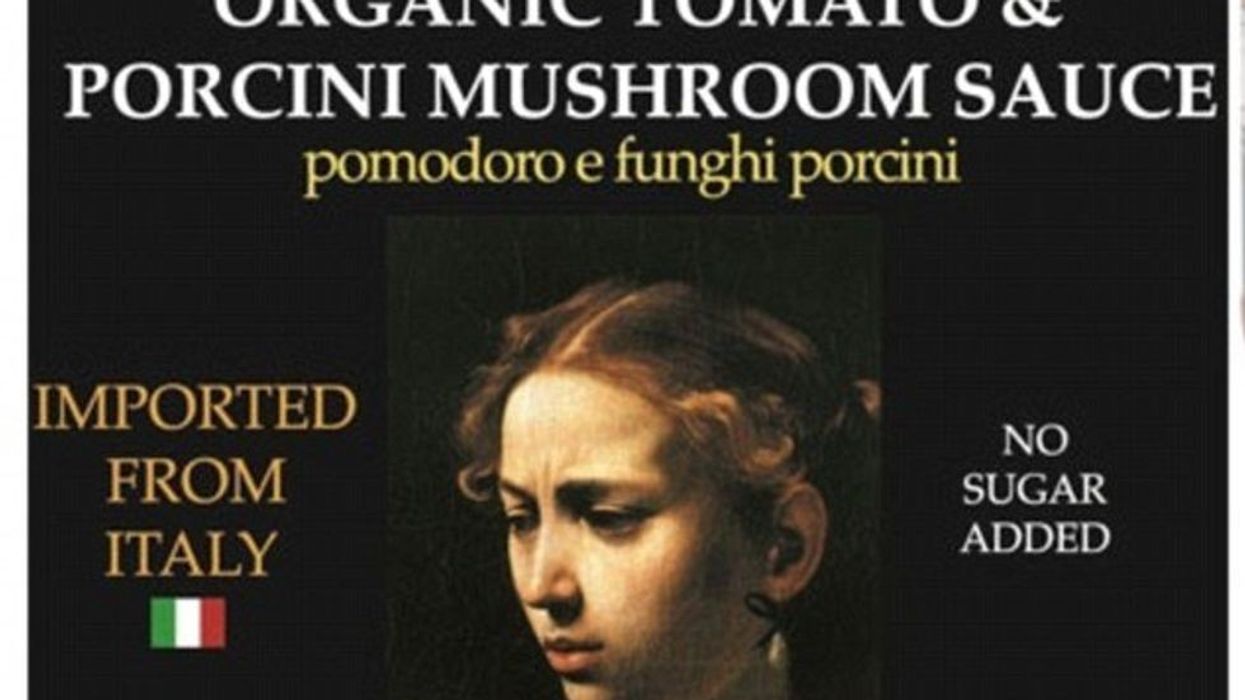

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)