Sunday Worship

One muggy Sunday morning in April, a man named Boku rakes the rectangular, earthen courtyard that sits between the temples of Obatala and Shango, the Orisha deities of paternal wisdom and virile kingship. A middle-aged black man with sharp features and a wiry goatee, wearing a pristine white robe and turban that don’t quite cover the various pharaonic symbols (ankhs and eyes of Horus) tattooed along his arms and neck, Boku is an aspiring priest, sent to cleanse the courtyard in anticipation of the day’s devotions.

As he rakes, a series of women, ages 6 to 60 and clad all in white, enter the courtyard, swaying to beat of drums. By the time Boku finishes sweeping and takes up a metal bell alongside the drummers, at least a dozen dancers have gathered. Into their midst walks a priest, an older man with a staff and gourd, pacing, rolling his shoulders, and chanting to the drumbeat. The undulating crowd answers his incantations, and together, in a slow, circuitous choreography, they dance their way to the doors of Obatala’s shrine. One by one, they disappear inside to make offerings to the spirit.

Sitting in a rusty folding chair beside the three young male drummers, I’m mystified by the ritual. That’s largely because it’s performed entirely in Yoruba, the West African language of the cities of Ile Ife, Oyo, and their environs, where men first began to venerate the hundreds of spirits that make up the Orisha pantheon. But as soon as the 30-minute ceremony draws to a close, everyone in the crowd immediately switches back to English, the all-American accents a mixture of clanging Northern and syrupy Southern.

This is not shocking. We’re not in Yorubaland. We’re actually just off Highway 17 in South Carolina, in the sovereign, religious Yoruba city-state of Oyotunji.

Oyotunji sprung out of the low country swamps of the Ashepoo, Combahee, and Edisto Basin in the early 1970s. For years beforehand, the black men behind its founding had witnessed the continuation of riots, blatant racism, and subtler social injustices even after the legislative victories and cultural milestones of the civil rights era. Growing disenchanted with the prospect of real, enduring change in white-dominated America, they embraced separatism, building their own intentional community. Originally part of the black nationalist movement, elements of which stressed reviving the traditions of their pre-slavery ancestors to reassert the value and dignity of their heritage, they wanted their new society to be a place where African-Americans could find success in life by embracing their history rather than assimilating to white society. To build a space for that, they decided to recreate a Yoruba kingdom in exacting detail.

In its early years, Oyotunji sparked a great deal of interest, both from African-Americans enticed by its promise of a new world of possibility and from a mass media bemused by the transposition of Africana into a swamp down the road from the area’s well-heeled beach towns. But as black separatism and intentional communities fell out of vogue in the 1980s, and as the village ran up against serious economic challenges, interest flagged, and families started to leave in droves. The few reporters who still wander by every few years just to see if the place still exists now paint a picture of decline, using Oyotunji as a symbol of a fleeting chapter of radical American racial thought that no longer has any place in the world.

But if those reporters had stayed for more than a few hours, they would have realized that the village, while in some ways diminished, is actually in the middle of an upswing. Over the last decade, members of the second generation who left the village as teens have started to return, led by Adefunmi II, a new, charismatic “oba” (king) devoted to making the place welcoming and relevant. And they’ve been joined by a handful of other young black Americans, many with no prior connections to the village.

“They’re your everyday Americans. People looking for an answer,” says Adefunmi II, a handsome man in his mid-30s with a spark of youthful exuberance in his eyes and a manic skip in his step, even at his most hangdog and exhausted. “It’s getting worse too. People are coming constantly for help and the old priests are becoming overburdened, sometimes they have five-six people waiting to see ‘em. And those people won’t leave until they see ‘em.”

According to Adefunmi II, these newcomers are “damaged by the American experience” and curious about life in Oyotunji. They describe a creeping sense of alienation that mirrors the experience of the first generation. From the Ferguson riots to the Charleston church shooting that took place about 70 miles from Oyotunji, it’s not hard to see why it can feel like the hatred and tensions of the post-civil rights era never subsided, but have simply been simmering beneath the surface, waiting to boil over.

Yet these seekers and returnees seem to have a different vision for Oyotunji than their predecessors. While they still value the notion of connecting to their African heritage, the community’s current standard bearers no longer see the need for full separatism or a tightly regimented recreation of traditional African society. Instead they see Oyotunji as a retreat, where people can come not just to live, but for short stays to heal, observe a different model of life, and take what they learn back out into the world as agents of engagement and change. And rather than just teaching cultural recovery, they’ve allied with a growing wave of black urban sustainability movements, stressing the value of cultivating the land as a means of establishing ownership, building a sense of security, and providing community-building, culture-affirming therapy.

Fewer people live in this modern Oyotunji than in the Oyotunji of 40 years ago. But the way the community sees it, that’s not a sign of decline; it’s a sign of evolution. And key to this evolution has been the new Oba, who’s spent years transplanting the former king’s core ideals from their context of separatism and cultural recreation to a modern context of slipstreaming worlds.

Long Live The King

Sometime in 2005, Oba Adejuyigbe Adefunmi II, the 14th of founding Oba Efuntola Oseijeman Adelabu Adefunmi I’s 22 children, was on his way to work in Key West, Florida, when he got the call that his father had died. He’d known from childhood that he was destined to be the next Oba of Oyotunji, yet eager to experience the rest of the world, he’d moved south and spent his mid-20s as a stucco artist, reggae musician, and active member of the local social scene. But when he learned that his father had moved on to the next realm, he packed his bags and returned to fulfill his fate—only to find that his father’s village had fallen into disrepair.

“When I got back here, this place was broken down, man!” says Adefunmi II. “I was like, ‘oh shit.’ Roofs had caved in, trees had fallen down, nobody was around to repair it.”

Before he could start repairing the village, though, Adefunmi II had to follow the strict Yoruba protocols of succession and coronation, secluding himself in his father’s house for three months. Every day, the elders would cast oracles and perform sacrifices, trying to pass on all of the inscrutable bureaucracy, ritual, and order that they’d developed under the first Oba’s hierarchical hand—urging him to become a vessel for his father’s beliefs in the value of precisely replicating every little detail of a traditional, regimented African society.

But the young Oba had never been great with hierarchy.

“[My dad] used to call me reckless,” he says. “And yeah, I am. I’ve got a lot of spirits that walk around in me—I like to have fun.”

While Adefunmi II embraced the ideals he’d inherited from his father—the value of cultural dignity and the deep need for an alternative to the circumscribed lives he saw many black Americans living—he doubted that his father’s closed system, near-martial strictures, and corporal punishment regimen were really the right way to foster Yoruba culture. Living beyond the royal palace as a child, he’d seen people alienated, anonymized, and disaffected by that system. And as his reign began, he feared he was seeing those old problems resurface.

He decided that to honor his father's cultural legacy, he'd have to obliterate the old Oba's political system. In its place, he would build a culture that promoted leading by example and inclusive decision making.

The Monday Meeting

Sitting around the Kola Nut Kafe, the village’s social hub, the Oba and the town’s residents have convened to discuss community issues and their tasks for the day. In the first Oba’s time, daily duties would have trickled down via his layered, bureaucratic machine. But these meetings, in a way the essence of the new Oba’s leadership style, are all about consensus.

They still start with an invocation to the gods. Everyone kneels to the ground and taps the earth with two fingers while Chief Alagbene, a serene man in stately robes and one of the few remaining elders who has been involved in the community since the ‘70s, chants in Yoruba. The Oba begins the meeting with a speech on the value of, and honor in, collective labor, calling upon people directly to not shirk their duties. He peppers his speech with pop culture references and jokes, mentioning the memory-wiping pen from Men in Black as he waves around a Bic pen and implores people to keep their minds on task. He allows everyone to chime in, even children, blaming himself for errors and forgiving everyone for their mistakes.

“I’ve been told that I’m not as traditional as my father,” says Adefunmi II. “And my father knew it. He was afraid [of my reign]. … A major difference is the level of punishment that’s applied. My dad was—if you didn’t do [a thing], you were heavily fined, rodded, or stripped of your title. But all of that to me is the same bullshit that societies have been doing for a long time.”

Rather than embrace Yoruba procedure to a tee, the new Oba believes that it’s much more important to focus on developing trust and accountability in a small community.

“We have to meet on a human level at first,” he says. “Then we can dress everybody up in our fancy robes and do those [traditional] things.”

This shift in policy rubbed quite a few elders the wrong way. Some of the chiefs even left the community in protest, leaving just a few, like Alagbene, to support the young monarch.

But while many of the old chiefs have left, members of the second generation have been coming back, like Tade Oyeilumi, the Oba’s wife of just under a year who recently returned from years spent in the arts and fashion industry. And there are new members as well, some of them even considering paying the $1,000 to buy a plot of land in Oyotunji, which they would be free to develop however they saw fit.

Many visitors come to the village throughout the day for readings or rituals, some from as far afield as Georgia or Tennessee. Others come for the nightly parties, blasting a mixture of traditional music, pop, rap, classic soul, jazz, and R&B at the Kola Nut’s bar as people drink and make merry. Entire second-generation families visit regularly for a few days or weeks, introducing a third generation to the culture. Yet for all the festivities, joy, and sense of community, many of these people come because they feel a deep sense of malaise or dislocation from the wider world. I hear the term “post-traumatic slave syndrome” repeatedly used to refer to the continuing sense of cultural denigration in African-American communities.

Although a disregard for black lives and a dim view of African and African-American culture have long been a fixture of life in the U.S., many in the village, like Alagbene, think that for decades, especially from the 1970s into the 2000s, the nation fell into a lull of faith, rejecting separatism and similar philosophies and buying into a narrative of slow progress toward equality (or at least towards livability and basic respect for black America) spun through mainstream media outlets and in political discourse.

Yet over the last few years, especially in the wake of the 2013 murder of Trayvon Martin (and countless other tragedies before and after his particularly notorious death), the reality of modern racism has become not just a lurking sense but a front-and-center aspect of the American conversation. It’s sparked mass activism and public dialogue, as Alagbene sees it, eliminating the myth of gradual progress for many and pushing them to action. This realization has some seeking alternatives to, or refuge from, the mainstream, and Adefunmi II seems to have taken on Oyotunji’s restoration just in time to welcome this new wave of seekers.

Talking to new members of the community, it’s clear that they agree with this assessment.

Nubia Tamale, a self-possessed woman who just started visiting the village this year but is already thinking of buying land, says her connection to the town clicked when her daughter said something on their first trip.

“My daughter was just like, ‘Ma, I feel so free here.’ At 5, if something makes you feel free, you must wonder, what did you feel before you came here, and how do you not feel free at 5?”

In the end, she says, the spirit of self-creation and the communal nature of the place holds much more appeal for her than the 9-to-5 existence she’s lived to date.

“I’d much rather bust my butt eight hours a day for people around here and for my children than for your children’s children’s children, who’re going to be sitting pretty while my people have nothing,” she says, likely noting my own whiteness.

King to Oba

Why these modern seekers, or even the village’s first generation, would choose to embrace Orisha spiritualism as their escape from the mainstream remains opaque to many outsiders. According to those who’ve lived in the village for some time, the story of the rise of Yoruba traditions as a viable alternative to modern American life begins back in the 1940s, when Adefunmi II’s father, born Walter Eugene King in 1928 in Detroit, noticed that many of his Jewish and Muslim (i.e., non-Anglo, non-Christian) peers had numerous special festivals. When he was told there were no such holidays specifically for black Americans, it inspired a spree of curiosity.

In his 20s, King wound up traveling with African cultural organizations, encountering Candomblé, Santería, and Vodun (aka voodoo), syncretistic mixtures of West African spiritualism with Catholic overlays from the American South and Caribbean. Finding these traditions led him to feel that he and other African-Americans were the heirs to an erased cultural history and that only by reclaiming its heritage in full could the African diaspora move beyond the legacy of slavery.

“It is a profound ‘cultural void,’ which reduces the African-American imagination to impotence,” he later declared in a speech. “It is the loss of cultural hindsight [that] induces the evaporation of any self-willed vision of the future. This ‘cultural amnesia’ is the greatest abomination which can befall an individual, a generation, or a nation.”

Yet he was not comfortable with how Santería et al. leaned on Western icons and sometimes even denigrated darker skin in their rituals. So when he was initiated into an Orisha lineage in Matanzas, Cuba, in 1959, he decided to strip it of Western artifice, get back to its Yoruba roots.

Orisha, the belief system at the root of so many Creole faiths in America, was and is common throughout West Africa, especially among the peoples who were most targeted by New World slavers. A tradition still practiced by a fifth of all Yoruba (and familiar to anyone who’s read Chinua Achebe’s 1958 classic Things Fall Apart), it’s anchored around the veneration of one’s ancestors, acceptance of one’s inborn (if malleable) destiny, and the worship of a pantheon of up to 401 recognized spirits—often former humans from legendary times elevated into emanations of a supreme deity.

King and his compatriots recognized that the civil rights era of the 1960s wasn’t some magic bullet that had instantaneously transformed America into a post-racial paradise. They saw continuing riots and killings throughout the country as white populations bitterly resisted the new legal environment. These cultural seekers believed that the impulse to belittle African culture (belied by expressions like ‘darkest Africa’) and thus subjugate African-Americans, was rooted too deeply in the U.S. They decided they needed their own homeland—someplace separate from the inherent bile where they could thrive.

In the early 1970s, King and a group of over a dozen followers moved south to build a symbolic new nation. This city-state (named after the traditional capital of Yorubaland, Oyo, with the suffix “tunji” meaning “rise again”) would be a Yoruba monarchy, complete with extreme social stratification, a prominent place for priests, scarification rituals (three lines on each cheek at least), talking drum communications, polygamous and patriarchal families, and a reliance on divination, astrology, and herbal remedies.

King obtained a 12-acre plot and started building shrines and family compounds on a sliver of what was once an old plantation, bits of which were broken off and granted to ex-slaves whose descendants still live on the surrounding land. In 1972, King traveled to Nigeria to be initiated into an indigenous Yoruba priesthood. By 1973, he’d returned to his nascent village, where he took on the role of Oba Efuntola Oseijeman Adelabu Adefunmi I, a title confirmed when he returned to Nigeria in 1981 and was named king of all Yoruba in the New World by one of the tradition’s highest spiritual authorities. Oyotunji was born.

Milk and Honey

The community got off to a rocky start, as rumors spread in nearby towns that these strange new neighbors would abduct visitors and might even practice cannibalism. But despite persistent whispers about occult practices, the community has since established solid ties with the authorities and is recognized by the state as a tax-exempt religious organization.

At its height, the village attracted a fluctuating population of between 150 and 300 residents and drew national press attention—it was an article in Ebony that first piqued Alagbene’s attention.

“The village images [in it] intrigued me,” he says. “But I was still a little unsure because right about that time was the Jim Jones thing in Guyana and people drinking the Kool-Aid. The word ‘cult’ was going around.”

So Alagbene decided to visit the village in 1978, holding onto onward bus tickets so he could beg off if things were too weird when he showed up.

“[But] when I started coming down the dirt road to the village, I began to feel something. I wasn’t sure what it was. … What I say now is that [the] hole in my soul began to fill up. I’d been looking for cultural-spiritual connections all of my life, really. … And after three days, I knew that was where I wanted to be.”

He became an “ilari,” a member of the king’s bodyguard, and settled down for good. He rejected his old name, started participating in the creation of Africanized art (a huge cultural anchor in the village, born as it was out of the African cultural movement), and started learning the form and language of Yoruba culture.

Like everyone else there, he didn’t actually know when he arrived whether his ancestors had been Yoruba, or some other West African peoples, or even slaves drawn from much further away, like Angola, the Congo, or even East Africa. But he was eager to embrace the tradition as his own. The village legitimized people’s connections to the Yoruba as well, by performing “roots readings.” In these rituals, priests or priestesses would divine one’s ancestry (invariably tied to the Yoruba or neighboring peoples with similar beliefs, like the Fon), ascribing to individuals a place within the hierarchical structure of Yoruba cultural life via their own innate destiny.

“[Through these readings], it’s no mystery as to what your place is and what you’re going to do,” says Adefunmi II. “That’s what’s missing today in the lives of Africans in North America: They do not have that African spirit.”

Out of Eden

Although many people rushed down to Oyotunji with high hopes and a ready spirit of volunteerism, life in the village was tough. At the start they had no water or electricity, and they rapidly became overcrowded and strapped for food on their isolated plot of land. Some current residents believe the initial settlement focused too much on teaching religion and language and too little on the logistics of housing, feeding, and economically sustaining the deluge of people who wanted to join the village. As a result, over the coming years many left out of the sheer necessity to find gainful employment and security for their families.

Of those who stayed, eventually many of their children (there are hundreds, if not thousands, of men and women who spent some of their childhoods in Oyotunji) started to yearn to experience the outside world and to escape the stigma they faced whenever they wandered into it.

“We used to all say, ‘Can’t we just be normal?’ ” recalls Adefunmi II, adding that local kids used to make fun of his scars, saying things like, “Is your father Freddy Kruger?”

Many of that first generation of Oyotunji kids left, eager to sample life beyond the village and see if they could transfer their distinctive culture into a wider world, laying the ground for the realities of modern Oyotunji.

As they left and the village’s numbers thinned out, the elders at the heart of Oyotunji started dying as well. In 2005, Adefunmi I died at age 76.

Even if this had been the end for the village, Oyotunji’s legacy would have been assured. The group has allegedly initiated hundreds of priests in their Orisha tradition, and Oyotunji’s leadership helped foster the creation of Yoruba-centered Vodun temples to the spirits in many major American cities. Some experts claim that at times there have been as many as 10,000 followers of the tradition in the U.S. alone.

“It was a seeding of America,” says Adefunmi II. “It’s growing now. There are trees and forests in damn near every city in America. It’s beyond what my father could have imagined.”

Oyotunji could have faded away, becoming a relic of the past, a museum of a culture and faith now disseminated to a constellation of local outposts. But the work of the new Oba and his growing cohort is instead transforming their parent’s community into something new and distinct from the sort of “Vodun Vatican” it had become. That’s only partially a result of the Oba’s stress on inclusivity and community building. Most of Oyotunji’s new energy is rooted in the Oba’s alignment of the village with a growing wave of empowering and replicable sustainability movements.

A Sustainable Future

Everyone at Oyotunji today believes the village needs to change to address the shortcomings that led it down the road of decline in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Because while young black Americans face racial tensions shockingly similar to those their ‘70s predecessors fled, they come from a very different world.

“That’s why I feel that the ancestors are bringing us through,” says Nubia Tamale. “It’s time for the new energy to start. The older people who have been in the village for a while, they don’t understand what 2015 Matrix life is like.”

Not everyone in the village can articulate what that change will look like, or exactly how it will serve African-Americans in 2015. But to the Oba himself, both the village’s new direction and the function of that trajectory are excruciatingly clear: Oyotunji must root itself in a culture and ethos of sustainability.

Part of this is practical. To avoid the same economic crisis, disillusion, and breakup of order and dedication that afflicted Oyotunji after its zenith—to preserve the village as a space for future generations—the community must make viability its first priority.

“This is not the place for 200 people to live in harmony and joy,” he says. “What are we going to do with their shit?”

But part of it is principle, too. In a world where no one, save increasingly problematic and highly politicized groups (like the Nation of Islam or the New Black Panthers), talks about separatism as a solution anymore, the Oba recognizes the need to not just deliver cultural dignity, but also cultivate a well-rounded, practical, less dogmatic life around the culture.

The Oba says he draws inspiration from the works of Milwaukee’s Will Allen and his urban farming organization, Growing Power, which stresses the therapeutic value of working with the land and owning your own space and food security. Building on Growing Power’s model, which he studied directly, Adefunmi II hopes that he can make Oyotunji a node of this sustainability movement. He wants to use farming to heal those who come to him, creating the space in them to accept a new lifestyle and then equipping them with the tools to go back into the world and create their own gardens—refuges in which their communities’ cultural and personal dignity can grow.

“We’ve always started people out with the esoteric business—put on some beads, then drum, dance until you feel the vibe. You can do that in any religion. … [But] our vision is to provide that which was lost, which is the true foundation: How do you grow your own food from nothing? Composting, feeding yourself, building your homes in a fashion where you’re not creating another junk pile. I’ve found that working with the earth is a good conduit to producing a good human.”

He sees his Oyotunji as a beacon on a hill (or in this case a drum call coming from deep within the swamps)—a model community that other cultures and traditions across the country should mimic, rather than a separatist retreat. And he hopes that spreading these communities will help African-Americans escape the same cycles of poverty and denigration that his father tried to break with an exacting model of Yoruba life alone.

“The idea of Oyotunji should have been mimicked already. I mean, come on America!” he says. “We could mimic this in every city in North America and have the young black kids growing up with more than just what the media shows them.”

If The Orisha Will It

The Oba’s not certain that his vision of a cascading laboratory for nationwide hubs of sustainable, nurturing communities rooted in the Yoruba tradition will come to fruition. After all, although he’s playing with all sorts of projects from micro-gardens, to earthships and mud architecture, to solar power, Oyotunji is still far from sustainable. Rather than agriculture, the economy now depends on tourism and the occasional grant for green projects. And many locals subsist on tinned Vienna sausages and potato chips despite the Oba’s pleas for residents to eat at least one handful of kale and mustard greens from his gardens with every meal.

“We haven’t even left the porch,” the Oba says of his sustainability goals. “We could be so much further ahead!”

He half-jokes that if he can’t get the locals on-board with his vision, he might have to hire outsiders and start running the village as a Vodun center for the droves seeking spiritual guidance in an increasingly fraught reality.

Much of the village’s progress is also worryingly tied up in the charisma of the Oba himself. Eyah Ibeji, a young woman who moved here last fall from Key West, says the village relies heavily on the Oba.

“Every time he leaves on business, the atmosphere is like—” Ibeji lets out a sigh, feigning the sadness of someone who feels left behind.

Plus, despite the community’s newfound energy, it’s still woefully under the radar for most Americans—even those who have lived in the area and traveled through the region all of their lives often have never heard of it.

People here have patience and faith, though. They honestly believe that, even if they screw it up once or twice, or move slower than expected, they’ll reach a future of sustainable service.

“[The first Oba] said it would take us probably a hundred years to have a real, smoothly operating organization,” says Alagbene.

“My hope, and I think it’s attainable, [is] that in five to eight years we can scale up to a point that we’re self-reliable if not sustainable … because we have a start.”

The community doesn’t necessarily need to work magic to make that happen. If members are right about what they can offer—a refuge, temporary or otherwise, that appeals to marginalized peoples in the modern era and gives them the tools to go back and change their own communities—then they’ll continue to attract visitors as long as America’s very public racial contentions continue. It certainly won’t be the retreat that every disaffected seeker needs. But it can at least be an option for those looking for a refuge to explore. For the village, it’s all about whether those arrivals can be channeled into funds, labor, and the realization of the Oba’s vision of sustainability.

If the village can survive, it can serve. And Oyotunji’s lessons of cultural dignity and community—some reclaimed, some hard-learned, and some forward-thinking—can cascade outwards, providing many who feel marginalized with a sense of identity, belonging, and security.

Volunteers at the St. Francis Inn pray together before serving a meal on July 19, 2021.

Volunteers at the St. Francis Inn pray together before serving a meal on July 19, 2021. Police close down a section of Kensington Avenue to clear a homeless encampment on May 8, 2024.

Police close down a section of Kensington Avenue to clear a homeless encampment on May 8, 2024.

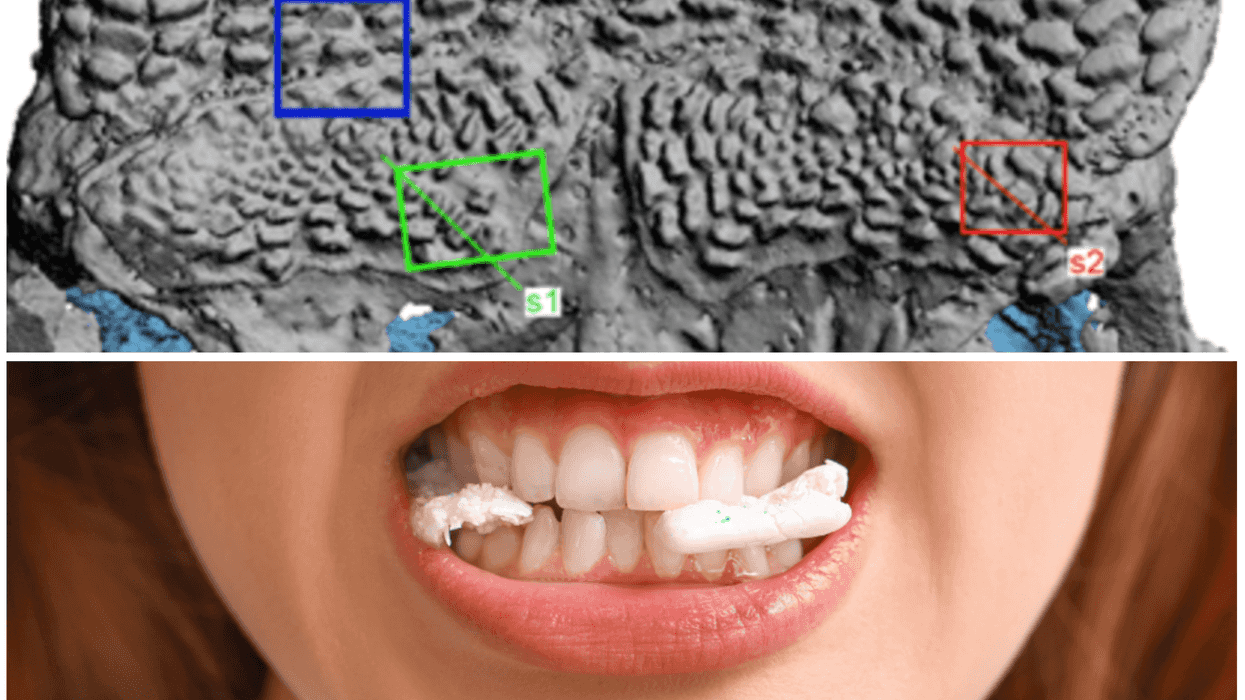

Left: A robotic arm. Right: Rice grains.Photo credit:

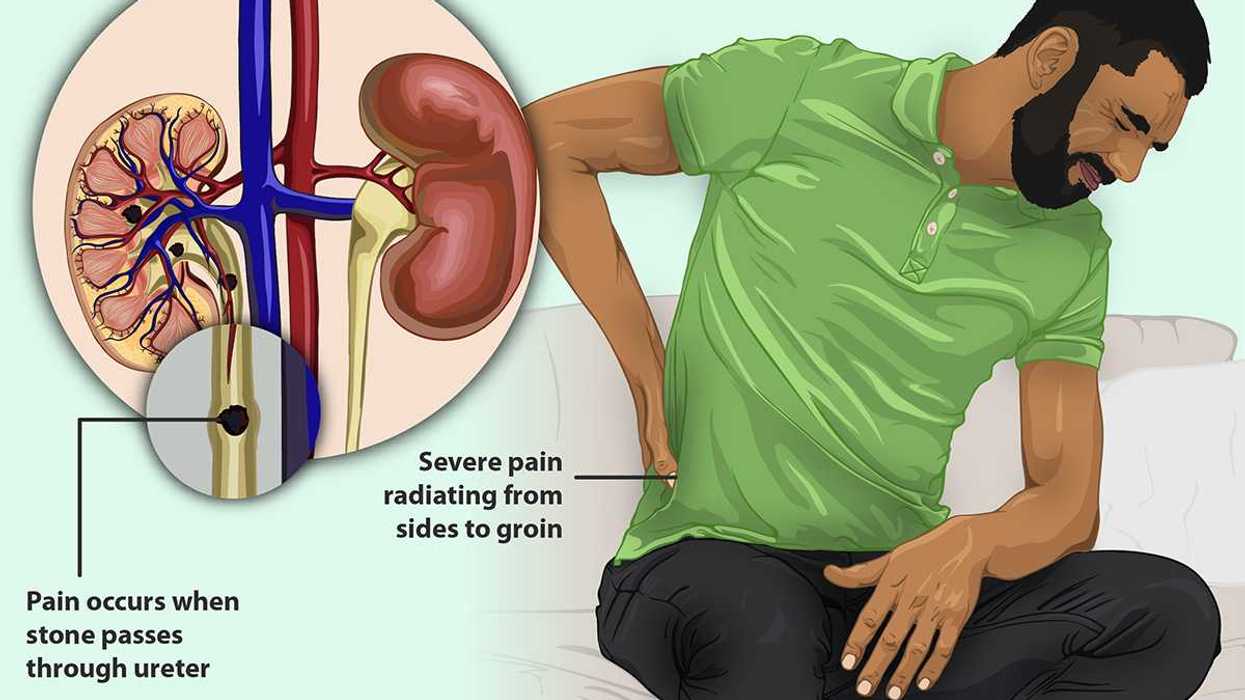

Left: A robotic arm. Right: Rice grains.Photo credit:  A diagram on kidney stones.myupchar/

A diagram on kidney stones.myupchar/

A couple engages in a serious conversationCanva

A couple engages in a serious conversationCanva

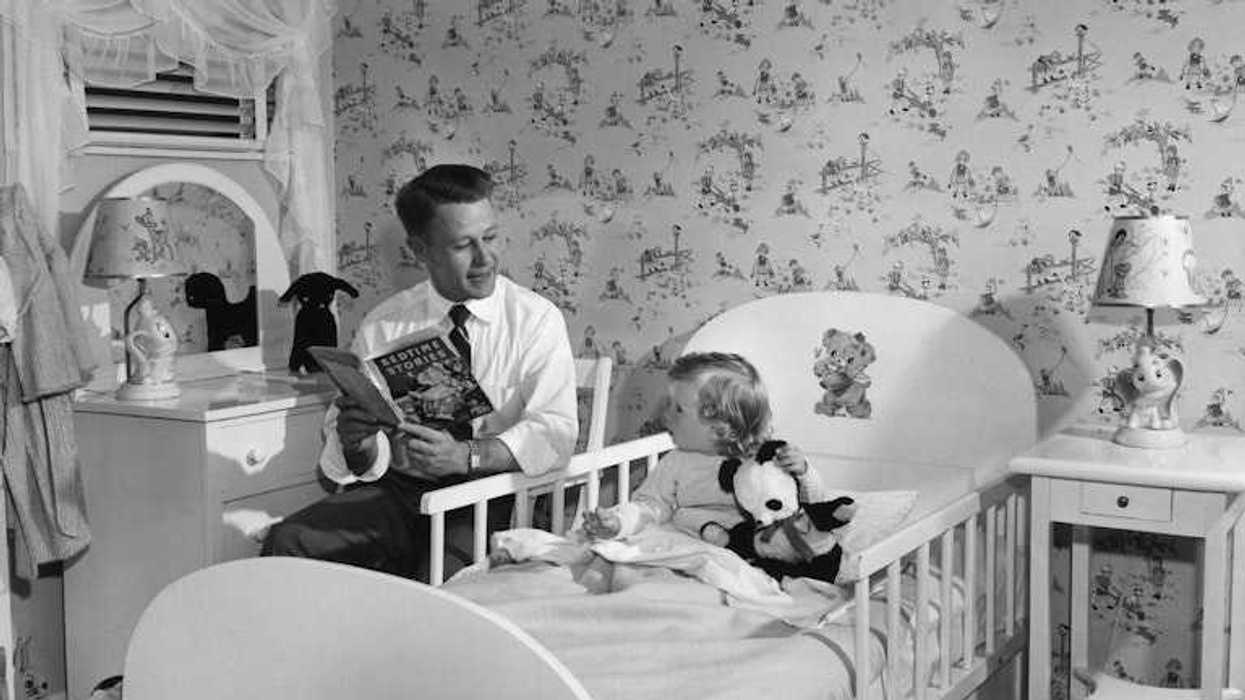

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025.

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025. Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.

Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.