Stepping off the plane in Kingston, Jamaica, the oppressive heat is the first thing to make me sweat, but it won’t be the last. The bustling corridors at Norman Manley International Airport smell fragrant like dew rolled into freshly baked sweet bread. Everyone here looks like me. But then again, everyone is staring. No matter how much I try not to call attention to myself in my nondescript shorts and sneakers, the island can tell I’m just visiting. I was born here, but I’m not from here. The sun isn’t baked into my skin, and there is a layer of America-fed bigness filling in places it shouldn’t, shrouding me like a capitalist monk on a diplomatic sojourn.

The thing is, I don’t really get how everyone here is so skinny. Beyond Bob Marley, Marcus Garvey, and the reggae, the food reigns supreme. There’s the beef patty and coco bread, a doughy pastry filled with piquant beef or chicken, rolled in a dust of black pepper, curry, and thyme, and baked to a crisp. There’s curry chicken—a heaping of curry slathered on pieces of short cut chicken meat. And, of course, there’s oxtail that sits gallantly atop rice, brown and garlicky with a sweetness that saturates down to the bone after spending ample time getting tender in the pressure cooker. Yet the culinary highlight of my pilgrimage home and back is (and always will be) escovitch fish.

The ingredients are simple enough. The fish can be any species, but a meatier fish is always best. The open-air markets in Kingston or Spanish Town might have kingfish or, if you’re lucky and adept at haggling, a vendor might unearth some red snapper from beneath their stall. Bring it home and immediately add vinegar, salt, pepper, garlic, an onion, pimento, and scotch bonnet peppers. (You’re familiar with scotch bonnets if you’ve used Tabasco or paprika; Columbus supposedly hustled some back to Europe after visiting South America.) The pickling is done differently by different folks. The north side of the island has its very own hint of culture. While our family’s recipe is peppery and light, others add a hint of sweetness by adding sugar. My grandmother simply sautés the onions, garlic, and scotch bonnet together until the onions are translucent. The fish get their spicy rubdown with the salt, pepper, and pimento. Then she’ll pour the vinegar in with the scotch bonnet and let it pickle.

The term escovitch comes from escabeche, a Spanish cooking technique that calls for marinating meat in an aggressively acidic potion with a vinegar base—the rabbit, pork, or fish then becomes preserved through the pickling process. In Spain, chefs practice the method at culinary schools across the country, but for my grandma, she was born with it built into her hands. Instead of carefully measuring, she can perfectly eyeball the ingredient amounts through the entire process. When I ask her to walk me through the steps, she becomes obstinate: “Just do it,” she’ll say.

Two days before my return to the States grandma disappears in the early morning, the crunch of rocks underfoot as she walks down the dirt road. Sometimes she’ll return empty-handed and tell you the fish didn’t look good that day, but on this morning, she came back bearing big, bright specimens—with glassy eyes that my parents will eventually pluck out to eat when the fish has been picked clean. (Older Jamaicans often spare nothing, you see.) Once the fish has been prepared, I watch as her small frame heads into the backyard to roast the fish over an open wood flame. Smoky and hot, the scent wafts into the house, filling every inch of open air. There’s four of us to feed—maybe more—and she roasts extra fish to put in our suitcases for the flight home.

Before the cousins drive us to the airport, my grandmother places her hands on my face and tells me to stow the fish right away, and it’s then that I understand those fish are symbols of her love. When I arrive at Customs, a young worker asks if I have anything to declare. I say, I have some escovitch fish and hard dough bread to declare, some breadfruit and callaloo, too. I leave out the tins of ackee, the salt fish, and the coffee. They let it slide that my suitcase is now 10 pounds over its sanctioned weight. The flight back stinks of vinegar, onion, and the sea.

Back home, my parents wait to break out the fish until the next morning, slowly unwrapping it from its newspaper coffin like a hard-earned prize. A pot of the smuggled Blue Mountain coffee will be set to brew. We spread butter on our hard dough bread. My mom toasts hers so the butter melts straight away, but I like my butter thick and choppy like waves—fighting the grooves for space. As I bite down, each piece explodes into a buttery, flaky texture. The wafts of scotch bonnet burn my nose, causing it to run. And my fingers become stained as I pick every sliver of meat from the fish’s bones. If we’re lazy, we’ll warm the escovitch in the microwave, saying a little prayer that granny would forgive us. But today, we put the fish into the oven to warm. That way, the fish heats up uniformly, and the juices remain until we put it into our mouths.

We survive solely on imported escovitch fish until Sunday, when mom puts on gospel music, and we know it’s time to clean up from the trip. From our suitcases emanates the crisp smell of onion and allspice—a reminder of Jamaica that will linger on our taste buds long after we are settled back at home—the escovitch fish that connects me to my heritage.

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

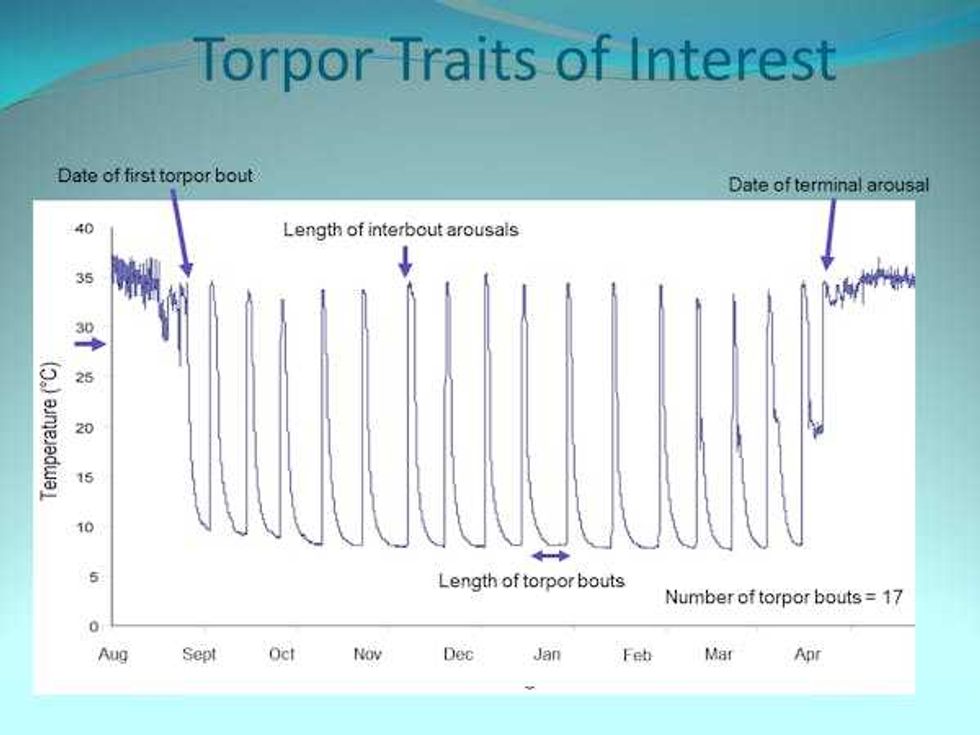

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva  A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

People voting. Photo credit:

People voting. Photo credit:  Young women rally. Photo credit:

Young women rally. Photo credit:  Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/

Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/

Winter weather.

Winter weather.

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from  A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from

A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from