For decades, critics of single-payer health care have raised the menace of rationed care, long waits, and "death panels."

Now, in our collective national effort to "flatten the curve" — to slow the spread of coronavirus to prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed — we are seeing all three of these rumored pitfalls of "socialized medicine" in our for-profit system.

After all, the entire point of "social distancing" is to ration available care. Meanwhile hospitals are postponing elective surgeries, and hard-hit places like Washington State are discussing plans to determine who gets critical care at ICUs and who will be turned away.

At first the federal response to the pandemic was slow, as public officials spread false information, claimed they had contained the virus to a few individuals, and refused World Health Organization offers to help the U.S. develop its own COVID-19 test.

Since then it's taken more aggressive steps. But in the long term, it would be better to put in place a system to prevent and address crises before they threaten to end life as we know it.

It is too early to say which countries will prove most successful in containing the virus, but there are indications that those with single-payer systems have the advantage.

As Helen Buckingham of the Nuffield Trust told The Washington Post, the U.K.'s National Health Service is well-positioned to cope. It has a clear and comprehensive emergency planning structure with the ability to optimize resource use, even after years of government budget cuts.

Federalized health care means centralized patient information. As Kelsey Piper reported for Vox, Taiwan's ability to get information quickly from citizens' medical files, combined with proactive containment, enabled testing for the virus as early as December.

Despite high traffic with mainland China, Taiwan only had 45 confirmed cases of the disease and one death in early March.

Similarly, South Korea's aggressive testing and universal coverage helped the country "flatten the curve" more effectively than any other so far.

Importantly, single-payer health systems are far less costly. At over $10,000 per person each year, Americans spend far more on health care than any other wealthy country, yet our life expectancy is lower. Because of these out of control costs, many of us avoid going to the doctor altogether — another form of rationing.

For example, my last trip to the gynecologist was so expensive, due to both improper coding and an in-network test sent to an out-of-network lab, that I have yet to go back. A year and a half later, I continue to receive bills for a 50-minute preventative care check-up.

Avoiding the doctor for fear of the cost is bad in the best of times, disastrous in a crisis like COVID-19, and unheard of in places with single-payer care.

Certainly, single-payer is not a magical solution: Italy has a federalized national health insurance system similar to Canada's, and its northern regions are overwhelmed by the outbreak. But Italy's leadership was slow to recognize the pandemic and communicate that reality to its citizens.

Yet the rapid response in other European and Asian countries shows that, though single-payer systems are not a cure-all, they are able to better prepare these countries with clear emergency protocols, efficient information collection, and free access to care.

Rationing care, long wait lines, and "death panels" aren't what awaits us in a socialized system. They're hallmarks of our failed for-profit system, which is simply not up to the task of providing for our public health.

If we continue to put our political and economic ideologies ahead of our health, we stand to lose everything.

This article was originally published by Common Dreams and written by Ashar Foley.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026. Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit  Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

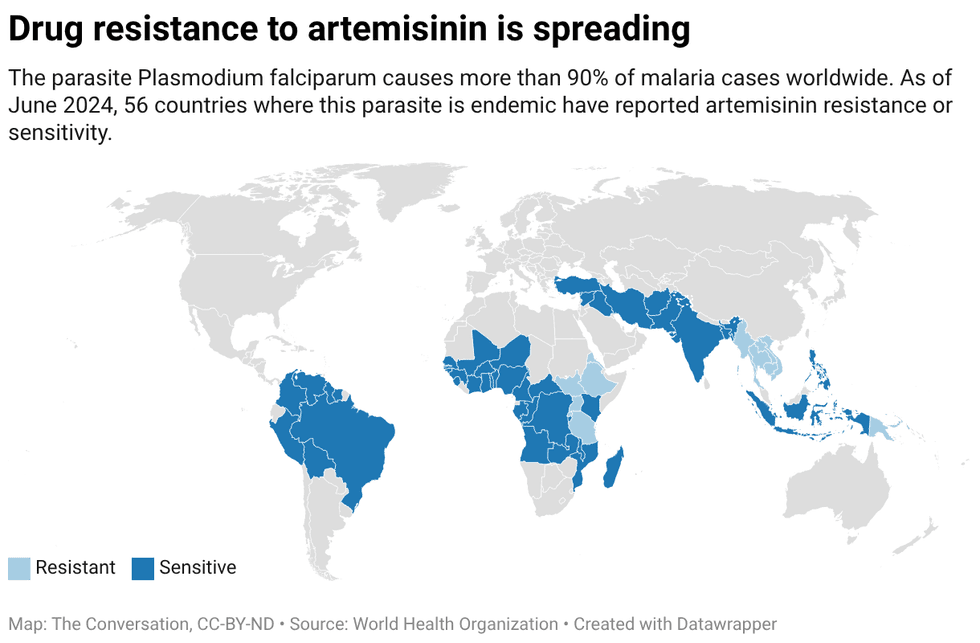

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with