Have you ever wondered why you can’t tickle yourself? Or why some people are more ticklish than others? Or why certain spots on the body are more susceptible to tickling? Or why tickling is even a thing? Well, the Donders Institute in the Netherlands hopes to figure all of that out.

On behalf of the Donders Institute, a team of neuroscience researchers led by Konstantina Kilteni opened up a “tickling lab” at Radboud University in Nijmegen, Netherlands to test, research, and hopefully answer those questions and others that Socrates had over 2,000 years ago.

Kilteni believes that the research into tickling would not only give us answers to those questions, but also grant us better understanding of how our brains work and help us to see if there is any evolutionary benefit to tickling.

“If we know how tickling works at the brain level, it could provide a lot of insight into other topics in neuroscience,” said Kilteni. “Tickling can strengthen the bond between parents and children, for instance, and we usually tickle our babies and children. But how does the brain process ticklish stimuli and what is the relationship with the development of the nervous system? By investigating this, you can learn more about brain development in children.”

@winela.world Are you ticklish! I am... #tickle #science #evolution #body #laugh

Kilteni also found an answer to why we can’t tickle ourselves, but the more interesting mystery they hope to find out is how.

“Apparently, our brain distinguishes ourselves from others, and because we know when and where we are going to tickle ourselves, the brain can switch off the tickling reflex in advance,” she explained. “But we don't know what exactly happens in our brain when we are tickled.”

The tickling lab is conducting several different neurological tests and experiments regarding tickling that haven’t been seriously considered previously. One example is doing various tickling tests involving persons with autism to see if there are any patterns on a neurological level, given that they typically are more ticklish and sensitive to touch compared to non-autistic individuals. Other experiments involve testing different types of tickling and seeing how the brain reacts. While tickling is considered a catch-all term, being tickled by someone’s fingers in your armpit is different from when your feet are being tickled by a feather for example.

The current experiment involves the subject putting their feet into two holes positioned under a chair. A mechanical rod then tickles the foot soles. Meanwhile, the neuroscientists are measuring what’s going on in the brain along with the heart rate, perspiration, and laughter or screaming volume and duration during the session to find if there are any correlations.

“By incorporating this method of tickling into a proper experiment, we can take tickling research seriously,” said Kilteni. “Not only will we be able to truly understand tickling, but also our brains.”

Even though we are still discovering the various questions of “why tickling?” we have found some benefits to it. As Kilteni mentioned, the act of tickling can strengthen bonds between parents and children, close friends, and romantic partners. It’s also a fast-track method to create laughter, which has been shown to reduce stress, release dopamine, and boost your immune system, among other health benefits. There are also studies that show that tickling ears could even reduce aging in adults over 50 years old.

@feleciaforthewin Im sorry but PAYING to be tickled is actually psychotic 🤣🤣🤣 but no judgement… do your thing? lol #psychology #psychologyfacts #asmrsoundsdaily #greenscreenvideo #greenscreen

That’s not to say that everyone should just tickle everybody for their health. Some child experts say that even though a child laughs from being tickled, it doesn’t mean that they enjoy it. Tickling could overwhelm a child (or an adult for that matter) and have them not feel in control of their own body, with laughter being an automatic nervous submissive response to an aggressor rather than a sign of enjoyment. This plays into many of the questions we still have about tickling, in that the act doesn’t have a universal response. It’s important to ask and check if a person or child wants to be tickled before engaging in it.

With time and experimentation, the Donders Institute will hopefully find new discoveries about our brains that will tickle our curiosity.

Winter weather.

Winter weather.

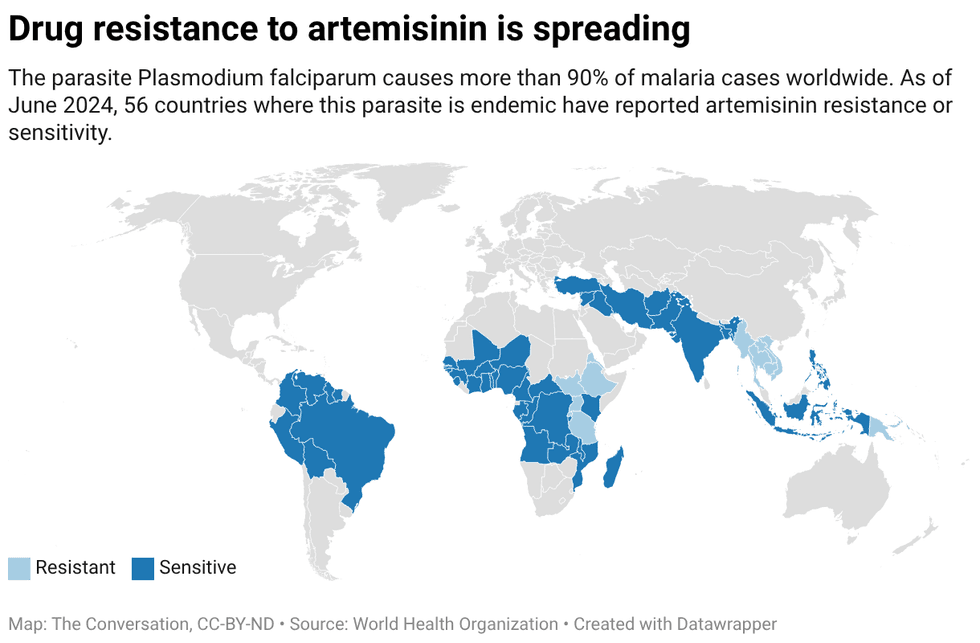

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

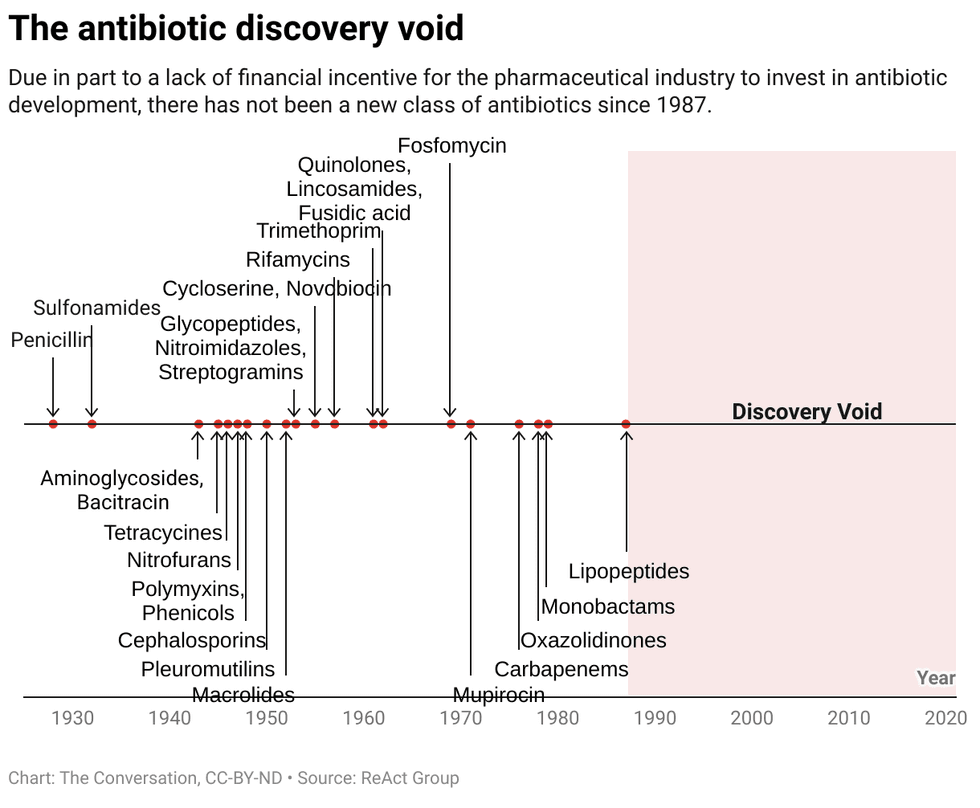

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.